Beware — this is also a House of SPOILERS.

A brain, an athlete, a basket case, a princess, and a criminal are taken from their daily routines and confined together in a stark, oppressive environment. They squabble and connect and learn uncomfortable truths about themselves. Then they torture each other, physically and mentally, just to survive. To my knowledge there has never been a movie adaptation of House of Stairs, despite it having one of the great elevator pitches: the Breakfast Club go to hell.

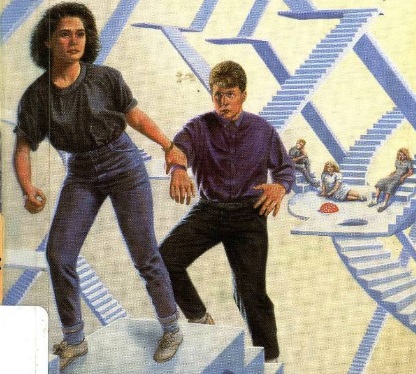

Instead of everyday teens in a nice Midwestern suburb, the 16-year-olds in William Sleator’s novel are all orphans and wards of the state in a not-too-distant future where resources are scarce and the environment is increasingly toxic. Thoughtful mediator Abigail, confident jock Oliver, dreamy introvert Peter, manipulative brat Blossom, and abrasive daredevil Lola wake up in the title building, an unending series of staircases and landings with no top or bottom, no walls, and one toilet. And one food dispenser — a box that spews out tasty pellets that taste like meat, a rare delicacy in these days. The food is accompanied by a flashing light and odd noises that sound like voices, although each teen hears different words. But that’s when the food comes at all. Because while it first gives indiscriminately, the machine soon stops providing — unless the kids start doing things to each other.

In a thoughtful obituary of Sleator for The AV Club, Emily Van Der Werff accurately pegs his prose as “rarely anything other than functional,” but adds “he had a unique talent for spinning various science fiction concepts together into a larger tale that offered plenty of fodder for insecure younger readers.” The sci-fi setting here is a great one and it builds to a reveal that would fit right into a Twilight Zone episode (Sleator’s dedication — “to all the rats and pigeons who have already been here” — is a tip-off). But it’s the strong emotional understanding of character, and the characters Sleator chooses to understand, that carries the book, especially as YA fiction. Sleator’s teens are grappling with their own faults, the ones they’ve been conditioned to embrace, even moreso than the hell they’ve been placed in.

Sleator lets us into each character’s point of view but the leads are Peter and Lola. Lola is coded pretty butch — short hair, tough talk, a smoker — and she has dark skin. She’s someone who’s taken some knocks, but will take no shit and doesn’t care that people don’t like that. Peter, on the other hand, is not coded at all; he is clearly gay. While Lola constantly talks and acts, Peter responds to stress by withdrawing into daydreams that are nearly comas, dreams where he remembers an older boy in his old orphanage who made him feel safe:

“Jasper, sitting on the bed and taking off his shoes, smiling, punching Peter on the shoulder and telling him not to worry. …Jasper’s strong, hard body as he got into bed, so different from Peter’s. Strong, to protect him, to take care of him.”

This is not subtle stuff. But Sleator threads a narrow needle here, making Peter’s sexuality part of who he is but subordinate to his all-consuming need for affection and protection instead of healthy desire. This, not homosexuality itself, is what’s unhealthy, and it leads to a dangerous dynamic between Peter and Oliver, the other guy in this house, who happens to resemble Jasper a great deal.

Oliver is definitely straight, though. He’s an outgoing, naturally assertive dude, a life-of-the-party type who jokes discomfort down, but he also needs to be in control — deprive him of that and he lashes out. Abigail, the other explicitly straight person, is a conciliator. She’s smart and kind and able to see all perspectives. But that means she doesn’t commit to her own. They have the closest thing to a romantic relationship the novel provides. It does not go well:

“There was shame, shame and acute embarrassment at having done something so intimate and so wrong. But more than that there was a kind of terrible responsibility. What did it mean to this girl that he had touched her that way? What would she expect from him now? And would he be able to live up to her expectations? She was watching him, startled by his sudden pulling away; and from her parted lips and dazed, half-closed eyes, he sensed she would still like to be kissing. Abruptly he turned from her…”

“But … but I thought you wanted to,” [Abigail said]. “You started it. They always said boys wouldn’t respect girls who … did that but I thought it would be different in here. Oh Oliver, please tell me what’s wrong?”

“…He couldn’t tell her his real reasons: There was something unmanly about them.”

Abigail’s “I thought it would be different in here” is a small moment of heartbreak. Placed in hell, she has the capacity to see that maybe she can enjoy things she couldn’t elsewhere. But the behaviors she and Oliver have learned in the outside world are too strong to resist. Three cheers for heterosexuality!

This makes the non-sexuality of Blossom seem like an intelligent life choice, although that is just down to her own self-regard — she has no interest in others. She’s prissy and piggish, and for all the times she’s referred to as fat, she’s also the thinnest character. But even here Sleator has some insight into personal truth. A person who only thinks of herself has to manufacture her own emotional sustenance, and Blossom will never let herself go hungry. “Hate is a bottomless cup,” she quotes Euripides. “I pour and pour.”

But she needs real food too, and the machine has stopped providing it. Until a weird moment when everyone in the group is moving and gesticulating and shouting at each other — then it kicks loose with just enough sustenance to provide energy, if not assuage hunger. Lola, the quickest thinker, comes up with a plan. The machine must have responded to something they did, so they should try repeating their actions. They hone this into a dance of sorts, complicated steps executed over and over, at it works. For a time, enough time for the teens to start responding reflexively, unconsciously when the lights flash and the whispering starts.

Then the machine stops responding to the dance they know, but starts responding to more violent extensions of it — instead of shouts, insults. Instead of waves, slaps. Instead of frustration and fear, hate. A skill Blossom is ready to use, and teach — even though the machine is the real teacher.

Which Lola, who is also the most rebellious and determined, belatedly realizes. So she opts out. And to her surprise, so does Peter. They won’t dance, they won’t eat. Somehow. But together. “I need you, if it’s going to work,” Lola tells Peter. “You are essential.” That means Peter can’t withdraw into his daydreams and must grow into this responsibility of being necessary and not a burden. And Lola has to swallow her pride and asks the others for help, to fight as one against whoever is making this torture happen: “If we all stand against the machine together, then they’ll see they can’t control us. They’ll give up, and we’ll be the winners.” It’s an impassioned argument, which Blossom rejects with incredulous laughter. Fight and not eat? Preposterous! And first Oliver and then Abigail agrees. So Lola and Peter leave, and the other three keep dancing.

Peter and Lola begin to starve, while also fighting their own bodies that are conditioned to move at the sound of whispering voices and the flash of lights. And Peter has to fight his mind as well, which is conditioned in its own way to take the easy path of giving in. But in their battles with themselves, they have each other, with Lola using a mix of pep talks and disapproving withdrawal to help Peter learn to bring himself out of his self-imposed trances, to develop the self-worth of an equal partner.

Peter and Lola waste away, but to get their food Abigail, Blossom and Oliver create shifting groups of two against one, planning petty humiliations and thefts and attacks that are rewarded with pellets. None of these alliances lasts, though, leading to “a total mistrust, an incessant wariness, like the constant expectation of a blow. …They no longer saw one another as people, but only as things to make use of.” And it’s a short jump from seeing people as objects to treating them that way, and if Peter and Lola refuse to dance, they might as well be beaten for their audacity to fight the machine.

It’s a fight that can’t be won, of course. Lola finally breaks, not out of pain or misery but because of something deeper. The force of will that makes her fight refuses to let itself be extinguished. Survival trumps winning. She tells Peter she’s going to get food. Peter has fully moved out of his head by now and is even weaker than she is, but he’s also lived with weakness for longer and is ready to die. He’s horrified by her choice and the choice he makes is Sleator’s great coup:

“If he did not give in, and let himself die, she would know for the rest of her life that success had been possible, and that she had let herself fail. Whatever was going to happen to her in the future, it would be far worse for her if she had to bear the future alone. And he realized that even more important than the fight against the machine was his caring for her. He could not desert her.”

Giving in is a betrayal, dystopias say. It’s the the key moment in 1984, where Winston Smith doesn’t just break under threat of torture but puts the burden on Julia instead. You give in to your worst fears, or to the machine itself. But what if you give in for something, not to it? Peter decides that a battle lost together is better than a battle won alone. Helping a friend trumps winning. But he makes this decision and sacrifice alone, telling Lola that he too wants to live and that he’ll join her surrender. They start moving toward Abigail and Blossom and Oliver, and that’s when the men in white suits come.

Because of course this was all an experiment, as the slightly too generous epilogue reveals, an experiment that in the end was called off due to fears of starvation without the knowledge that Peter and Lola had been coming in anyway. In a bit of Psycho-esque scienticianing, the lead researcher describes the setup to the five participants (and an unseen audience of government officials), laying out the rationale behind artificial conditioning:

“One of the great problems of the human race is that the conditioning most people receive from life, from the real world, is unplanned — haphazard and accidental. Is it surprising then that people are only rarely well adjusted? …No wonder that so many people are frustrated and dissatisfied (if not worse), and therefore do not perform with maximum efficiency.”

This conditioning was designed at the behest of the U.S. President himself, to create a group of people who would follow orders no matter how “distasteful” they may be, according to Professor Explainitall. But while Lola and Peter screwed up the results, the experiment still had a 60-percent success rate. More tests are likely. In the least believable part of the book, Lola and Peter are to be sent off to a literal “island of misfits,” not just beating the machine but winning an escape instead of a couple bullets and an unmarked grave. But Sleator hasn’t completely left 1984 behind. He closes with a killer final line, following Blossom, Oliver, and Abigail as they hurry across the military base where all of this took place only to come face to face with a blinking traffic light: “Without hesitation they began to dance.”

House Of Stairs is a slim book, barely cracking 160 pages. For a book about teens stuck in a dystopia, it has no conspiracies, no revealed lineages, no systems to overthrow — the little why we get is not nearly as important as the what these five people do and who they do it for. Oliver and Abigail fail to connect sexually despite their urges, but the love and caring between Lola and Peter is more revolutionary for its Platonic aspect. Lola rewrites her own conditioning of self-centered resistance to include Peter, making him an equal partner, and Peter rewrites his own conditioning twice — first by refusing to withdraw from life, and then by backing down from winning at all costs — to save Lola’s belief in herself. They are all each other has, and Sleator says holding onto each other in the face of the machine, of the system, is a more powerful act of resistance then fighting alone. Because of who they are, Peter and Lola have already been excluded from certain systems. Maybe that gives them an edge. Or maybe anyone can resist with anyone else.

But you need that real connection. Blossom’s self-interest and Oliver and Abigail’s attraction without vulnerability and self-respect lead to the same place, conditioning that creates a closed system that can be rewritten with further conditioning by people with the means and will. A system that resists resistance. The big joke of The Breakfast Club is that the Brain winds up doing all the damn homework anyway, and the second biggest joke is that its most maladjusted characters, the ones most frustrated and dissatisfied and not performing with maximum efficiency, find themselves altered into more machine-friendly people. It’s a happy ending: everyone learned something from everyone else, cue the soundtrack and its melancholy but hopeful chords. The ending to House of Stairs may be too happy in some ways for Lola and Peter, but it’s a happiness that is for them only, and only at great cost. It doesn’t pretend there is anything good about joining the dance.