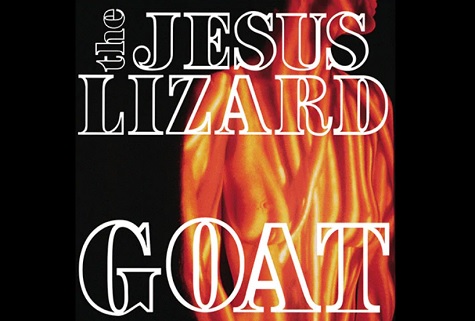

What was the greatest band of the 90s? There are as many contenders as there are definitions of “great,” which can encompass historical impact, influence, record sales as well as the music made by the band. I’m more interested in that last factor, which could be examined by a slightly different question: What was the best band of the 90s — the group that as a unit played at the highest level? That has a clearer answer: The Jesus Lizard. Exhibit A: Their 1991 album Goat.

The band — Duane Denison on guitar, David William Sims on bass, David Yow on vocals, and mostly Mac McNeilly on drums — grew out of Yow and Sims’ group Scratch Acid, and Scratch Acid was the U.S. band that most eagerly picked up the fervid torch lit by The Birthday Party. They weren’t as horny as that group, unlike Cave’s insinuating baritone there is zero Jim Morrison in Yow’s howls, and their thrashing felt wilder. Both bands were depraved, but The Birthday Party channeled Christopher Lee’s menace while Scratch Acid was Bill Paxton at the bar in Near Dark.

Eventually Yow and Sims and Denison left their home of Texas for Chicago and hooked up with McNeilly and the label Touch and Go, putting them alongside fellow depraved noise freak Steve Albini (Sims played in Albini’s short-lived group Rapeman as well). Albini engineered their albums at Touch and Go and was a crucial element of their sound; just listen to 1996’s Shot to hear what can happen to a good group without production that understands what makes them great. But before that was the four-album run the band had for Touch and Go, which peaked with Goat. What made The Jesus Lizard such a powerful band was not just how their four elements each had their own emphasis and texture, but how those elements existed in the same space without bleeding into or pushing in front of each other and still maintaining unbelievable tension, how the whole was so much more than the sum of its parts.

But what parts! McNeilly was the last addition to the group, who had recorded their first EP with a drum machine. This is how Albini’s legendary group Big Black (who had just called it quits) also played and the relentless, remorseless beats certainly fit the ugly and menacing tone. But they do not have McNeilly’s swing or his power, and the way they combine in the feel of a pro boxer working a heavy bag or an enforcer working a bagged body — the strikes (especially on the snare) rolling into and off what they hit, not just individual blasts but momentum. McNeilly is one of the few drummers who could actually be called Bonham-esque, listen to the Levee-ish thump of album opener “Then Comes Dudley.” This is a man with all the time in the world, so his fills and assaults hit all the harder:

The drums kick off “Then Comes Dudley” in sync with the bass and McNeilly’s restraint in attack is met with Sims’ propulsion, the latter is looking for a fight. Hooks and melodies appear in Jesus Lizard tunes but not in ways that lead to sing-alongs. What drives the songs are Sims’ riffs and what fills the riffs is his tone, a fat overdrive like a guy with a beer gut that turns out to be hard as granite. The Jesus Lizard got classified/denigrated as “pigfuck,” a signifier of aggressive ugliness, and while the whole band contributes to the abrasive sound I think more than anything the bass’ meanness is at the root of this — the band could soundtrack someone fucking a pig, Sims plays like he wants to fuck the pig. Side Two track “South Mouth” is a showcase for McNeilly and Dennison and Yow, all flying off the handle, and they do this around Sims’ looping pendulum of a riff that in the choruses slides through frenetic high triplets. You can hear the squeal.

With Sims and McNeilly taking charge, Denison can take off. He’s more than capable of rock-centric leads (the hair-raising, throat-slashing slide of “Nub”) but the fullness of the rhythm section lets him emphasize texture as well as heavier riffs. His playing has more than a little surf in it, trebly echoes that are ominous instead of placid, but there is twang as well that can turn into sheets of noise. “Karpis” showcases all of these modes, along with some weird, almost ska-like pings at one point, but it’s not showing off — these sounds are deployed to create mood. It might seem odd to describe Denison’s seemingly-unhinged licks in songs about things like prison rape (see above) in this way, but he has taste.

So yeah, those song topics. “Karpis” refers to the notorious bank robber and describes in great detail his trading “a carton of smokes for 10 minutes of pleasure,” the title of “South Mouth” indicates the subject, “Nub” is about a lopped-off limb. These narratives are not easy to hear, literally — Yow’s vocals often need a lyric sheet to be deciphered. They’re placed within the mix, not above it, so specific syllables are harder to discern in the first place and enunciation is often not the main goal. But that doesn’t mean Yow is being cavalier with his instrument. He inhales the microphone and screams away from it, mixing snarls with sobs and croons with mutters, screams with whispers and threats with insinuations. The words tell part of the story, but Yow is also focused on mood and atmosphere before snapping at the listener. The verses of “Seasick” are hard to make out, what is plain as day are Yow’s shouts in the chorus: “I CAN SWIM! I CAN’T SWIM!” The words negate each other. The unsettling menace is clear:

The Jesus Lizard built their reputation on absolutely ferocious live shows, with Yow venturing all over and above the crowd along with dropping his pants and throwing out hilarious non sequitur stage banter. I never caught them during the 90s but saw a 2009 reunion show and can confirm the band’s intensity and madness was still going strong nearly 20 years post-Goat (with Yow still in fine form in between songs — “That man is my father!” he blared about a guy in the audience who was definitely not his father. “We had sex three times and he never came. Except twice.”). That notoriety was well-earned but I think it obscures the work behind the wildness. “We practiced all the time, and we toured all the time, and we recorded with any time that was left open. Once we had enough songs to be reasonably long enough for an LP, we’d just record it,” Yow told an interviewer in 2018. The band’s members had been playing in some form for the better part of a decade — they had honed their skills and styles in countless gigs and practice sessions. The chorus of their song “Mouth Breather,” according Yow, came from a direct insult Albini leveled at the drummer from legendary postpunk band Slint, who had visited Albini’s house and fucked up his toilet, it’s crude and hilarious and off the cuff. The song itself is anything but, whatever the hell is going on with the time and rhythm (it’s apparently in 6/8 but good luck pulling that out from the riff and drums snaking together) doesn’t happen by accident. This is the work of professionals, however pantsless they may be:

“The band makes 4/4 time seem like an enormous playground, far from the view of authorities,” Sasha Frere-Jones wrote in a New Yorker piece about that stretch of 2009 reunion shows. Time and space, concepts of play I usually associate more with jazz than rock. Different bands and different genres have different strengths and endless variations, I’ve seen quiet rock and ear-shredding jazz. One is not better than the other, but The Jesus Lizard play them together in a special mix. The ferocity and sleaze and swing hotwire your guts and limbs and lizard brain, to hear them is to lose control to their careening precision and be exhilarated – maybe jazz comes to mind because of how it makes me think of another small group of men filling space with rhythm and fury and fire.

The album closes with the sick joke of “Lady Shoes” and the circling menace of “Rodeo in Joliet,” both fine songs, but its centerpiece is the great “Monkey Trick,” one of the band’s best-loved tracks. Sims’ jagged riff, a crosscut saw pushing and then carving, interlocks with McNeilly’s syncopated bear trap of a beat into an absolutely monster groove that Denison filigrees over while Yow mutters menace. “This one, it stops right here” is a clear warning, but to who? About what? The song rises and falls into a seething bridge. “An absurd gag, a monkey trick,an Irish bull, a childish joke!” Yow screams as Denison’s guitar turns into a shower of nails, he and Sims and McNeilly are all pulling apart in a three-way Chinese finger trap that paradoxically only makes things tighter before Yow comes back to wordlessly shriek some more. This is the band at the peak of their power and it leaves me in thrashing, neck-snapping spasms. “Body parts all over this town, what are they doing?” Yow wails as the song ends. Being the best band of the 90s, that’s what they’re doing. Being the GOAT.