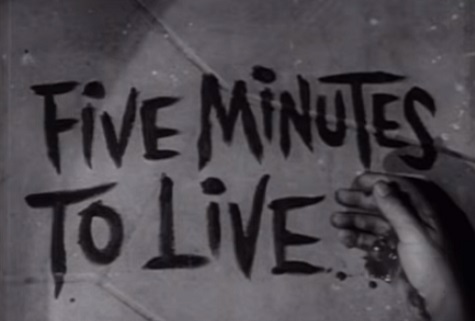

Johnny Cash has been everywhere, man. Of travel he’s had his share, man. But the perils of the mountain air and the deserts bare don’t hold a candle to the most dangerous place of all, an environment that destroys any outsider, no matter how tough: the suburbs.

Five Minutes To Live is Cash’s first and nearly only feature film role, aside from A Gunfight a decade later. Cash’s Sun Records labelmate Elvis Presley made two dozen movies, two in 1961 alone, generally playing sunny versions of himself in sunny locales and fitting into that fucker Col. Tom Parker’s plans for the brand. Cash wasn’t tied to a controlling manager, and in any case, he was not a generally sunny singer, and his movie is built around his badass persona. He opens it killing two cops in a botched robbery, and a short time later, he finds out his sassy and brassy girlfriend was the one who narked him out. He wastes no time and shoots her dead.

This frees him up for the main story. On the run from that opening cop-killing, he hooks up with old-school That Guy Vic Tayback, who has a brilliant plan for a bank robbery in a boring small town. Tayback has scouted out the bank’s vulnerable point, nerdo vice president Donald Woods, who has access to the vault and also a wife and son. When Woods goes off to work and the son goes off to school, Cash will break in and take wife Cay Forrester hostage and Tayback will use this to force Woods to give him a ton of cash. The insurance: if Cash doesn’t get a call from Tayback every five minutes after a certain point, he’ll kill the wife. This isn’t far off from the bank robbery scheme in The Friends Of Eddie Coyle, which works very well until it doesn’t, and it’s a good plan here, but there are complications.

The robbery is set up, with Tayback confident in his plan and Cash jumpy, already on edge after spending several days hiding out in a motel on the outskirts of the ’burbs. And as the two spy on their victims from across the road, Woods, Forrester, and their son — a huge fucking dweeb by the name of Ronnie Howard — start their day. Forrester makes breakfast, which Howard petulantly but very accurately calls mush, and each time he does, the camera focuses on the extremely mushy and possibly inedible slop everyone’s about to eat. Woods rolls out for breakfast later than everyone else and openly admits to his wife that he’s hungover. There is an incredibly tedious, drawn-out conversation about the PTA and Forrester working the other ladies in town to get Woods a position of influence there in order to help his prospects at the bank. None of this, aside from those mush shots, is explicitly played as satirical, but the long scene reeks of settled standards and dissatisfaction. All of this, by the way, is courtesy of Cay Forrester herself, writing the script from a story by Palmer Thompson.

Here’s the other thing Forrester sets up — when Woods finally gets to work, he gets a call from Pamela Mason as Ellen, the mistress he spent the previous night nailing and getting hammered with. So that’s why he’s hungover! Mason and Woods have been carrying on for some time and she’s ready for him to commit. After some pressure, he agrees to run away with her to Las Vegas and get married. That’s when Tayback walks into the bank and Cash walks into the house.

When Cash comes by, carrying a guitar case and saying he’s selling lessons with a patter slicker than goose shit, Forrester lets him in and immediately finds out that was a bad idea. Like many musicians, Cash is a great performer, and here he is playing a person whose performative dangerousness parodies and emphasizes his actual danger. It’s not dissimilar to his singing, where he describes brutality and desire with the same wide-eyed sincerity. A smart reviewer says he “mixes the corny with the sinister,” and that gets at his menace well — he’s taking cues from one of the greatest screen villains, Robert Mitchum’s Rev. Harry Powell. He threatens and cajoles, smashes knick-knacks and presses against Forrester, berates her and demands she dress pretty for him. “This is the first time I got this close to a perfect wife, and I always wondered what one looks like,” Cash drawls. The movie was apparently rereleased a decade later under the admittedly awesome title Door-To-Door Maniac in a different cut that had a more obvious rape scene, and it’s very easy to see where that would slot in to the original version.

Cash plays his guitar, dropping the title song in pointed reference to Forrester. At one point his eyelids drop in a leer that strips the clothed woman in a glance. He walks around the house like it is his to do with as he will, but while he’s in charge, he’s still uneasy. This neat house and confined quarters are not his idea of living — at one point he tells Forrester, “I like a messy bed.” He waits for those five-minute phone calls that will let him know if Forrester will live or die, but the tension of whether each call will come takes a backseat to the tension of what he will do in the meantime, how long he’ll hold out.

Forrester plays along as much as she can, putting on a sexy dress and trying to read Cash’s moods. It’s an unheroic performance and a very real one, a person trying to survive 300 seconds at a time. Which makes it all the more perverse that when Tayback lays out the scheme to her husband, Woods has to think things over. A dead wife would simplify the whole running-off-to-Vegas-with-the-mistress plan! Something Woods openly tells Tayback by the way. But he ultimately can’t go through with it and keeps his faithful wife alive, agreeing to open the vault and hand over the dough.

Things don’t quite work out here — security guards figure out what’s going on, a fracas ensues, and Tayback is beaned from behind with a sock full of quarters. What a dupe! But all of this is keeping Woods from making his call on the five-minute mark. However, the line is already busy. The head PTA lady has called about a luncheon that simply must be attended, and Forrester is incapable of hanging up on her. As voiced by veteran actor Norma Varden, this woman is implacable in her inanity — she makes the Jerky Boys sound like Bob Newhart, steamrolling every hesitation and maintaining her blather with circular breathing that would make John Coltrane weep. Forrester herself is weeping with the inability to get her off the line and Cash is losing his mind with frustration — he’s a killer, but he plays by the damn rules — but neither can stand up the onslaught of PTA gossip. It’s a brilliant scene where the idiocy of the obstacle increases the anxiety. Finally, Varden is dismissed, and Woods is able to call — but little Ronnie Howard has come home for lunch. And a couple cops have also arrived.

Earlier on, Cash nearly walked away from the plan because of Howard — he doesn’t want to involve kids. But now that a kid is here he decides to go full Sizemore and take him hostage, grabbing the little goober and hauling ass out the door. One of the cops sees a man running away using a child to cover 70% of his body and immediately fires his gun; Howard goes limp. And Cash, already near the breaking point, fully snaps. He lays Howard down and immediately wastes the cop who shot at him before staggering toward the other cop, sobbing with remorse and ready to kill again. The remaining cop quickly blows him away, and it’s a grim scene for a minute until fucking Opie gets up and wanders over. When he heard the first gunshots he faked getting hit! Forrester and the remaining cop cheerfully congratulate him on his Junior G-Man ingenuity, ignoring that it led to the deaths of two other people, including the cop’s partner (who totally had this coming for shooting near a kid, but still). The good guys, or a statistically significant majority of them, won! Crime doesn’t pay!

The movie opened with Tayback narrating the setup; it winds down with him describing his fall — we now see he’s being interviewed by the cops who busted him. But the film isn’t over yet. It ends with Woods and Forrester on the road, Woods explaining that he told the PTA lady to call and tie up the line in order to give the cops time to get to the house. He does not explain that he has been banging someone else and nearly let Forrester get killed so they could have a new life — because he broke it off with his mistress and now he and Forrester are on that trip to Vegas he set up earlier (who is watching Howard during all this is not mentioned). No muss, no fuss — everything’s coming up Woods! The happy couple goofs off and drives into the sunset.

When Cash comes to the suburbs, the suburbs destroy him and blithely continue existing on their own terms. Cash is a menacing avatar of chaos but not an unstoppable monster — he’s fatally thrown off-balance by a housewife yakking on the phone. And there is no Stockholm Syndrome here, no insinuation that Cash’s energy is somehow freeing or a worthy counter to Woods’ buttoned-down adultery. Instead, he catalyzes Woods into giving up his affair, returning him to normalcy. And while he terrorizes Forrester, he doesn’t pierce the veil of her allegedly happy existence. She’s still glad to be with Woods at the end, gulping down that mush.

“Five Minutes To Live” was apparently written for the movie, and the song fits into the script. “That bell is gonna ring/This is a final fling/Ain’t no alternative/You got five minutes to live,” Cash deadpans, emphasis on “dead.” But he clearly has more on his mind. Inspirational posters say “Live every day like it’s your last!” and Cash, who did not fuck around, says you don’t even have a day: a vicious robber or a callous spouse could cut you down in the next five minutes. Anything could.“Hear the tock tick tock of the laughing clock/What can you do or say?/Maybe you oughta pray.” Johnny Cash the actor plays a mad dog who needs to be put down; Johnny Cash the musician stands back and gets the last word against a world that offers the comfort of ignorance and the illusion of stability, a sedate suburb where everything is in its right place. “Get dressed for your date or you’re gonna be late/Live a little while you can/Don’t you sit there and wring your hands/Here comes a great big sedative/You got five minutes to live.”