An’ now people just get uglier

An’ I have no sense of time.” — Bob Dylan

Odd coincidences aligned as I reread parts of Robert Aickman’s Cold Hand In Mine. Jonathan Richman’s “Vampire Girl” came on the radio as I read a story about a girl becoming a vampire; the description of an ungodly squawk from a cuckoo clock in another tale was met with a honk from an aggrieved Canada goose passing my park bench. Coincidence is a signpost, the intersection of the straightforward and the uncanny, and it is a traditionally a warning sign in horror that just as traditionally is unheeded by the person who stumbles upon it on his way into the dark. Which is why these coincidences were so out of place; gauche, even. Aickman’s lands do not have signs or maps.

This is not to say they do not have direction or recognizable features. Many of his stories revolve around things that are almost painfully mundane, like annoying neighbors or walks through childhood neighborhoods. The vampire story, “Pages From A Young Girl’s Journal,” won the World Fantasy Award and it is easy to suspect the relative clarity of the conceit and situation was a factor in its popularity relative to Aickman’s other tales. And his language is not vague, although his characters may not be sure of what they are seeing or experiencing; if anything his stories run toward the longer side (40-50 pages) and accumulate petty detail as they go.

But this detail never coheres, or if it does, it coheres into something beyond understanding. “The Hospice,” the best story in Aickman’s 1974 collection, is about Maybury, a traveling salesman who becomes lost and is forced to take refuge at the titular establishment, a place of “GOOD FOOD and SOME ACCOMMODATION.” He is late for dinner, he is informed, but still seated at a table by himself, away from the main group of people silently eating at a long table of their own. But he gets the same fare they do:

“There was an enormous quantity of soup, in what Maybury realised was an unusually deep and wide plate. The amplitude of the plate had at first been masked by the circumstance that round much of its wide rim was inscribed, in large black letters, THE HOSPICE; rather in the style of a baby’s plate, Maybury thought, if both lettering and plate had not been so immense. The soup itself was unusually weighty too: it undoubtedly contained eggs as well as pulses, and steps had been taken to add ‘thickening’ also.”

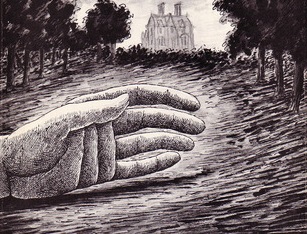

That first sentence tells the reader everything they need to know about the scene — big plate, lots of soup. But the subsequent sentences Aickman crafts, their commas and colons and semi-colons calmly guiding the reader around odd notes and suspiciously passive phrasing and uneasy phrases — “masked by the circumstance” — ultimately lead to a place of greater unease, despite the promise of more information. This is Aickman’s style, and it melds with story to great effect in “The Hospice,” which is set in motion by Maybury losing his way in a not uncivilized but unwelcoming area, with homes set back along narrow and heavily wooded roads. I have driven in isolated places but rarely felt more ill at ease than in the small towns west of Boston, past the second semicircle of interstate, where the hidden presence of people is more disturbing than their absence. Who knows what they are up to out there? Every sign of life raises more questions than answers, with one question overriding all others: What am I doing here?

In “The Hospice,” Maybury’s attempts to leave are cooly and perhaps sinisterly rebuffed by the building’s host, and he spends an endless night with an odd man in a dark room. Space contracts and time expands. The protagonist of “Pages” has more mobility at the outset as she travels through historic and decaying Italy with her stuffy British parents in the 1820s, a romantic and Romantic age (Byron is briefly glimpsed and much on her mind); but she is constrained by her youth and sex from actually doing anything. She has a sharp and clever eye that is being stifled by the constraints of her age and her own innocence, noting but not reflecting on the sight of a young girl being “hugged” in the dark by an older man. And she too meets and is enraptured by an older man:

“And yet I find it difficult to recall what subjects we discussed. I think that may be a consequence of the feeling with which we spoke. The feeling I not merely recollect but feel still — all over and through me — deep and warm — transfiguring. The subjects, no.”

The man continues to visit her, at night of course. Her focus narrows as she is exsanguinated, but her intensity sharpens into something exalted and inhuman. Her language becomes more entranced, a whimsical use of “farcical” in early entries, the kind of coltish pleasure a smart young person takes with a new word, becomes wearied. “I doubt if I shall write any more. I do not think I shall have any more to say,” her journal concludes. She willingly steps — floats? flies? — into a place that cannot be described to mere mortals.

The protagonist of “The Clock Watcher” is less active. He is not even the person named by the title. That is — probably — his wife, Ursula, a German woman he finds in the Black Forest, home of so many timepieces. He was there at the end of World War II, aconflict our man has fought in, despite noting that “there was a great deal to be said in favor of the Nazis, of course,” aside from their prejudices against Jews, who are “once a friend, always a friend, if you go on treating them properly.” He is a man who esteems his cheapness as shrewdness and who downplays generosity from others as his due for hard work, a man with an almost pathological lack of commitment:

“Most weddings are matters of equal gain and loss. It is not the wedding that counts, though so many girls think it is. Weddings are, at the best, neutral. Seldom are they even fully volitional.”

And yet he is committed to Ursula, Ursula and the clocks she is continually introducing to their bland suburban home in a bland suburban neighborhood where she keeps house all day while waiting for him to come home, surrounded by cuckoos and chimes that never quite align. This despite Ursula’s disinterest in, even fear of, time itself. “I can’t wear a watch,” she tells her husband when he suggests a personal timepiece, and later on he reflects that what she really said was “I can’t bear a watch.”

However, she can stand the man who comes to maintain the clocks, always when the narrator is at work. “No one may touch my clocks except the person I bring,” Ursula tells him early on. This is one thing our narrator can’t bear and he starts leaving work at odd times, trying to catch this mysterious (and according to neighbors, menacing-looking) person in the act. After one narrow miss, he demands to know who this repairman is, but is surprised by the appearance of yet another clock:

“And then — at that precise moment — a voice spoke right behind me. It was a new voice, but what it had to say was not new. What it said was ‘Cuckoo’; but it said it exactly like a human voice, speaking rather low, not at all like one of these infernal machines.”

The line connecting cuckoo and cuckold is obvious, but there is more at play here. Aickman gives no indication these meetings between clock owner and clock repairer are cover for sexual liaisons; Ursula is nothing but devoted to her husband. But she must maintain her clocks, and why she must do so is an unmappable part of her. And time is beginning to catch up to her. Some of her clocks are smashed by vandals while the couple goes on one of their monthly holidays to go do nothing somewhere else, and Ursula’s perfect appearance begins to age. She grows more anxious and upset and the narrator more bedeviled by her behavior. And the neighbors report that the repairman is angry. There is a final reckoning and a disappearance, which the narrator does not see, and at the end of the story he is no wiser than he was before, only more anguished. “There are no beautiful clocks. Everything to do with time is hideous.”

“Perhaps I was never quite an ordinary person after all,” the narrator muses at the beginning of his story. “Perhaps I ceased being ordinary when I married Ursula.” “Pages” is unique among Aickman stories in many ways, not the least for having a clear line of demarcation — the young girl is not bitten, although she is wasting away in other fashions, and then she is. But “Clock” and “Hospice” and Aickman’s other stories in this collection are less clear; even possible points of no return like marriage are not as clear-cut. His stories almost never play with time in the sense of placing events out of order to create a narrative (although a narrator will frequently relate lengthy asides of past circumstance in a larger tale) but they remove time as a function of narrative, not a measure by which a person orders events but an undertow pulling him along. What is a clock but the most reliable map in the world, marking the same territory no matter where you are? But it is yet another map that is no good here. Hours and minutes have little meaning for Aickman, because it is always too late.