It’s unfortunate but true: For the young cartoon viewer, the beloved Looney Tunes did not always deliver. Maybe a subpar Porky Pig installment elicited barely a chuckle, or the one-note antics of Pepe Le Pew grew stale, or the cruel taunts of an ageless demon inspired unease and fear instead of laughter. But even for the child who was willing to risk the disappointment of a failed laugh, there was one character who summoned not boredom or anxiety, but loathing and disgust — Sniffles the Mouse.

Chuck Jones, by every conceivable measure a genius, was still wicked and depraved enough to create Sniffles at the end of the 1930s with the help of Disney animator Charles Thorson and the voice of Margot Hill-Talbot, who seemed to be channelling the thin soprano of Adriana Caselotti’s Snow White. Wikipedia tells us Thorson’s design was based on a country mouse he originally created for the rival studio and drily notes that “both the country mouse and Sniffles are, in a word, cute.” A word is all there is to Sniffles, who has no personality or character. His wide eyes and squeaky voice and tramp costume of ratty scarf and raffish hat are carefully cultivated to produce only one thing: Awws. Sniffles has none of Jerry’s sadism or Mickey’s dutiful corporate accommodation. His very name insinuates the most adorable version of the plague, the rodent’s devastation sanitized into a sneeze. He is a pathetic and contemptuous creature, and he is waiting for Santa. Of course, he calls him “Santy.”

For some reason, the 1940 short Bedtime for Sniffles seemed to air every other week on my CBS affiliate, home of two hours of Looney Tunes every Saturday. For eight minutes — or about an hour in the short’s time — Sniffles tries to stay awake on Christmas Eve to see Santa and ultimately fails. That’s it. He sings to himself in a grating whine, he dances around a bit, he talks to himself in the mirror, he dozes off multiple times before finally succumbing to sleep. It is an utter fucking cheat of a cartoon, which is supposed to involve bonks and bangs and explosions, animals and humans tormenting each other.

It also happens to be a gorgeous, often witty cheat of a cartoon. Jones adapted a story by Rich Hogan and supervised Robert Cannon on animation, and the backgrounds that open the short, tenements covered in shadowy snow, are lovely evocations of a silent night before the holiday. Sniffles’ cutesy home is filled with cutesy touches that somehow work — a shaving brush is used for a Christmas tree and a walnut for a wastebasket, Sniffles drinks Haxwell Mouse coffee and boils the water for it on a stove made out of a Zippo — the detail and humor in these things makes them compelling as objects in a miniature world, not tchotchkes to be cooed over.

And Jones animates Sniffles’ odious corpus and wretched visage with incredible care and sensitivity, a Rodin sculpting in shit. Sniffles admires himself with insufferable jauntiness in a mirror, despicable in his existence, but brilliantly defined in angle of insouciance. He dances with hope and anticipation early on in the night, as Santa’s arrival is all but assured, but Jones really outdoes himself in facial animation. Sniffles’ enormous dome with its saucer eyes was surely created to allow for the greatest detail of emotion and the droop and weariness Jones describes, along with resistance to it, rivals the flaccid flopping of Michigan J. Frog in expressiveness. It is impossible to tolerate Sniffles, but it is impossible, watching him, to not feel as he feels.

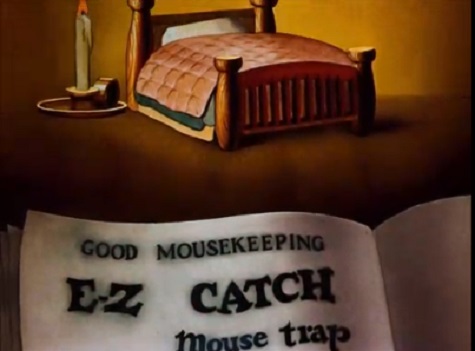

Toward the end of the short Sniffles tries to stay awake by reading a magazine (Good Mousekeeping, natch) which for some reason has an advertisement for a mousetrap — perhaps the publisher has been bought out by literal vulture capitalists. Sniffles looks up from the image of the trap to his waiting bed, and the juxtaposition is brief but clear. Perhaps Jones wanted to suggest, as Nas would do decades later, that sleep is the cousin of death, but here the link between the two is far stronger than secondary relation. And it’s reinforced by Sniffles hallucinating a ghostly version of himself already in bed, nightcap and all, crooking a finger to bring his corporeal counterpart to that final rest. Sniffles the Mouse floats into bed and merges with Sniffles the Ghost, finally acquiescing to slumber. Outside, a sleigh flies by and carolers sing “Joy To The World.” And the final card comes up: That’s All, Folks!

At some point, everyone in the world has fallen asleep when they didn’t want to. And at some point, everyone in the world will die. Sometimes art can let us come to terms with these truths. And sometimes it lets us thumb our nose at them, turn death itself into a joke. Imagine a house where a cat weathers endless head-cracking concussions while chasing a bird. A forest where a duck takes point-blank blasts from a shotgun and merely has his bill blown around his head. A desert where a coyote is smashed by boulders, exploded by dynamite, flattened by his own foolish speeding into a tunnel painted on a canyon wall, and yet picks himself up and continues his fight. There is no time to stop for death, let alone sleep, in these places of terrible, wonderful action and pain.

And imagine rousing yourself at the crack of dawn Saturday, escaping sleep and going downstairs to turn on the TV and visit these worlds of vicious, violent, funny life as you do every week, hoping in your heart for carnage and destruction and instead being shown a simpering mendicant of a mouse, puling and prancing for sympathy as he fails to stay awake, the most basic part of being alive. Watching something that does not mock sleep and death but mocks our resistance to it, condescending to it with a pat on the head. It’s a travesty, a sugar cookie packed with cyanide, a betrayal of the cartoon covenant.

There are things that can’t be stopped, but they can be fought with energy and wit, not ain’t-I-a-stinker cutesy-poo that inevitably ends in a self-indulgent yawn before snuggling into the grave. Bedtime for Sniffles is a technical triumph and a giggling embrace of oblivion. It elevates a mouse to destroy men. Foul rat! Vermin of the soul! The only hope the short leaves us is that Sniffles truly is dead, his pathetic life snuffed out while we still live. Joy to the world.