“Hateful day when I received life!’ I exclaimed in agony. ”Accursed creator! Why did you form a monster so hideous that even you turned from me in disgust? God, in pity, made man beautiful and alluring, after his own image; but my form is a filthy type of yours, more horrid even from the very resemblance. Satan had his companions, fellow-devils, to admire and encourage him; but I am solitary and abhorred.”

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Not many people like Alien: Resurrection. Alien is the scary one, Aliens is the awesome one, Alien 3 is the really dark one that’s secretly good. Resurrection is the one that, contrary to the title, ended the original franchise, leaving only prequels and Predators. Not even the previous movie –which actually killed the main character — could do that! Alien: Resurrection is the rejected child of parents who probably shouldn’t have been together in the first place.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. A script from hotshot nerd Joss Whedon! Direction from Jean-Pierre Jeunet, the Gilliam-esque visionary behind City Of Lost Children! A stacked cast of character actors, from Dan Hedaya to Ron Perlman to Brad Dourif to my man J.E. Mother Fucking Freeman! Also Winona Ryder! And lured back into the fold after pushing for Ripley’s death in Alien 3, Sigourney Weaver herself! On paper, it’s a can’t-miss scenario. And here’s the thing: It doesn’t miss, even though it doesn’t hit in the way its creators planned.

Alien is the horror movie, Aliens is the war movie, Alien 3 is the prison movie. One of the few appreciations of Resurrection notes some similarities to Day of the Dead and that points to its genre: the chaos movie. Zombies, serial killers, and monsters can all find a home here, where an organization (often the military, although private labs are involved too — see Jurassic Park) attempts to control an Obviously Bad Thing and fails miserably. The chaos movie is built to fall apart, it makes you anticipate and crave the carnage and fury of its X factor unleashed on the hubristic fools who thought they could control it. And then it has to deliver said carnage, hopefully with imaginative kills and gore. Resurrection more than makes the grade here. It is obsessed with spilled fluids — blood, acid blood, water, formaldehyde, afterbirth — that reinforce the idea of seeping, spurting destruction through the thin skin of bodily order as what was secure becomes something else. Chaos reigns!

But order must rule first. Instead of wild destruction, the movie opens with carefully controlled creation as military doctors on the spaceship USS Auriga clone Ellen Ripley — for the eighth time, it’s implied — using a sample of her blood taken from the planet she was imprisoned on in Alien 3, which takes place 200 years earlier. They’re not interested in her; they want the alien queen that was growing in her body and that she died to destroy, and they are successful in their harvest. Ripley is kept alive as an afterthought, though not without concern. The cloning process has made her a hybrid, and while she looks the same as ever, she has a xenomorph’s strength and acid blood and possible disregard for humanity — Weaver expertly shows through movement and gaze the not-quite-human consciousness living inside Ripley’s head, staring down her captors and shifting her limbs with the eerie ease of a xenomorph.

The doctors — led by Freeman’s cold and abusive Wren and Dourif’s enthusiastic Gediman — insist they aren’t like those bad old Weyland-Yutani corporate stooges (“Bought out by Wal-Mart,” we learn). And they have nothing but the best plans for the queen they’ve grown and the children she’s already had. Their unique biology will lead to all sorts of scientific advances for the betterment of all mankind — the military just needs a bunch of human hosts to keep growing their xenomorphs. Enter a rag-tag group of space pirates who’ve hijacked a shipment of cryosleeping miners and are willing to sell their cargo for a price. Despite an extremely wacky basketball showdown between Ripley and the pirates, everything is still under control. But all the pieces are in place. Time to get nuts.

Jeunet has kept things moving nicely so far, paying more attention to the janky, steamy design of the ship than its layout and mostly letting actors play their roles with at least 10 percent more emphasis than normal and this leads to some major tonal confusion in performance. Hedaya in particular is in a much goofier movie and Ryder is flailing around out of her league. But Jeunet is not really interested in the details of architecture or character development. What he is interested in is the messy ways human and alien bodies can collide with each other. Here is a partial list of incisions, eviscerations and other brutalities in Alien: Resurrection:

- Aliens use their tongue-heads to tear apart one of their own, in order to escape via the hole in the floor created by its acid blood

- Aliens bite human heads off

- Humans shoot alien heads into goo

- Aliens turn escape pod containing strapped-in humans into blender

- Aliens blast soldier with dry ice, freezing his arms off

- Alien impales man with tongue-head, leaving a gaping chest cavity that allows for…

- Human sticking gun through corpse and blowing alien’s head off

- Man with chestburster in gut holds other man’s head to his torso, chestburster tears apart both rib cage and face

- Alien blasts man with tongue-head squeezer to the dome, man reaches around and pulls chunks of brain out his shattered skull

This is chaos. This is gross. This is treating sentient beings like meatbags and it is gnarly as fuck. It’s important to note that a lot of this is scripted: Whedon is not averse to gore by any means. But Jeunet is the one who realizes it with a keen interest that is detached from (oh the) humanity. If he was shot in the head, he’d definitely try to pull his own brains out just to see what they’d look like. He’s aided in this by Darius Khondji shooting the dinge of the ship with warm colors gradually darkening and coating the aliens’ heads with extra KY jelly to get reflective pop. An old punk band name comes to mind — the Day-Glo Abortions.

And while this is generally a celebration of goop, Jeunet and Whedon’s sensibilities merge in the movie’s one moment of true horror when Ripley discovers her sisters, the previous unsuccessful clones, all mangled mixtures of alien and human DNA kept alive in stasis pods. Except for one, a twisted carpet of flesh with Ripley’s face that is out on an operating table and desperately, breathlessly whispering, “Kill me.” This is what the desire to perfectly engineer offspring and the intolerance of failure, the desire for control, gets you. The mostly male scientists mining her for genetic material — and the ship’s onboard AI, not so subtly named “Father,” as opposed to the “Mother” on Alien‘s Nostromo — paint a picture of a patriarchy that doesn’t even have the decency to madly consume its offspring like the gods of old. It merely rejects them if they don’t serve their purpose while keeping them around for spare parts, catalogued and filed as a few more inanimate objects. Ripley torches the room. The pods burst open, releasing the static fluid preserving a perversion of life and letting it drain away.

So the movie is now walking a weird line. We have the carnage we came for, but also a few characters that we theoretically are interested in. The fake Firefly crew joins up with Wren and a surviving soldier (a baby-faced Raymond Cruz) in a classic we-need-to-put-aside-our-differences scenario, and they meet the sole survivor of the hijacked miners, who is alive but has an alien in his gut just waiting to burst out (this guy is played with sweaty panic by Leland Orser, who between this and Seven had pretty much the worst psychosexual few years in 90s cinema). And of course there is Ripley herself, who decides to worry about who she is another day and concentrate on surviving today first. She’s the one who leads the crew through a fantastic setpiece where they make their way through a flooded and completely underwater kitchen area — more fluids flowing everywhere — only to be first attacked by swimming aliens and then led to a chamber full of eggs waiting to hatch.

If that wasn’t enough to deal with, Ryder’s whiny mechanic Call is revealed to be an android (really, people in this franchise need to expect this by now), one of a new generation that was recalled by the government but instead went on the run. But Call still has her programming and a bad case of self-loathing crossed with human envy. She hates doing anything beyond human ability — no knife dance over an outsplayed hand for her — and can’t stand being humanoid but not human herself. “Why do you go on living? How can you stand it? How can you stand yourself?” she asks Ripley. “Not much choice,” is the reply.

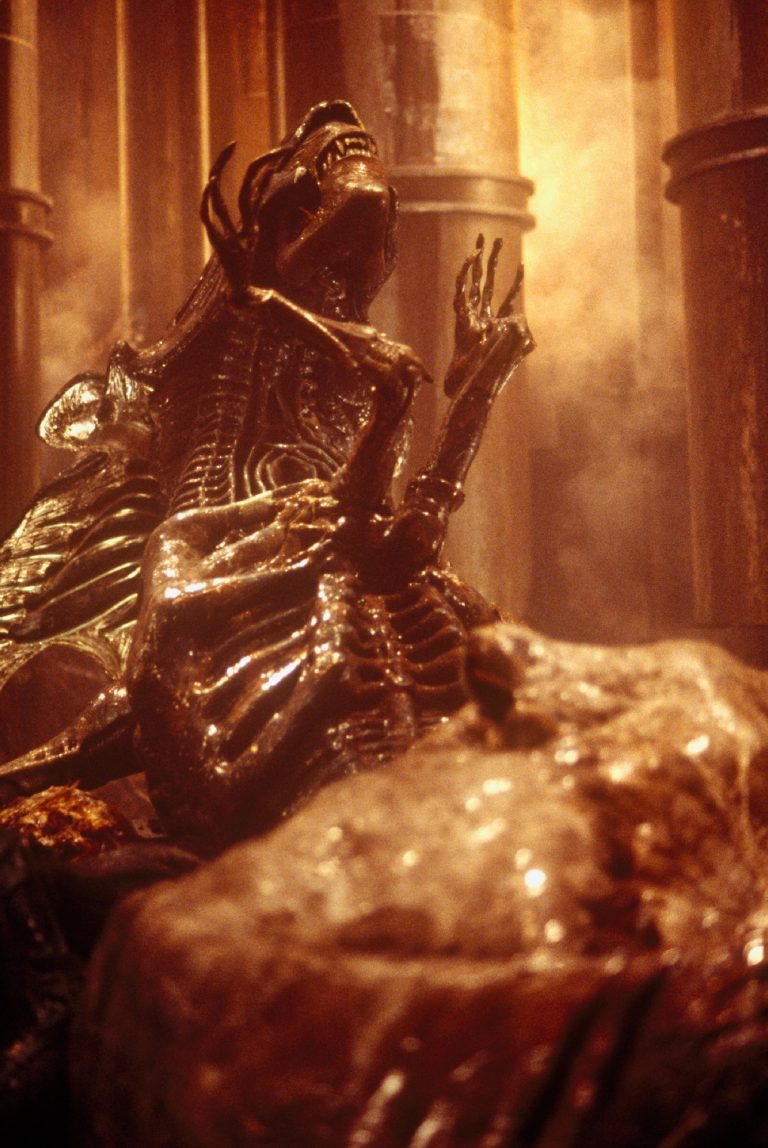

What choices does Ripley have? As the heroes are close to escaping, a few aliens grab Ripley and ferry her with loving care her through a writhing orgy of their fellow xenomorphs on the way to meet the queen that was pulled out of Ripley in the first place. And Ripley is strangely passive during this, as she was passive watching some of the crew die at the hands of her children (siblings? nieces and nephews?) earlier. This is who she is too, and she had no choice in the matter. She watches as the queen gives birth via a womb that comes from being mixed with Ripley’s DNA — it is hard to convey how awesomely gross this is — and instead of an egg, a new creature emerges. This Newborn is superhumanly large and has an elongated head like a classic alien, but it also has far more humanlike limbs and facial features, including eyes, than its siblings. And it has a human baby’s petulance, immediately ripping the queen’s jaw off and trashing her corpse. But when the Newborn sees Ripley, it approaches cautiously. Licks her face. This creature didn’t ask to exist either — no one has that choice. But it’s choosing her. And she could choose it.

It’s worth pausing here to return to Whedon’s original script, which is available online. There are plenty of minor changes but much of this is intact, with a few big exceptions. One is a more in-depth conversation between Call and Ripley: what we get in the movie has thematic resonance but doesn’t make a lot of actual sense. The largest difference is the ending, which in the script takes place during a battle royale on Earth — it likely would’ve added a huge amount of money and time to the shoot and was almost entirely axed, something I’m sure was frustrating, but bean counters gonna count beans (and I think what we ultimately get is more interesting anyway). The most important change, though, is this confrontation. In the script, the Newborn kills the queen and approaches Ripley, but then tenderly tries to fuck her with a dick that “looks mostly like a giant earwig” and gets pissed and murderous when Ripley is not dtf with said earwig dick.

It reads as incestuous and vicious and sends the Newborn down the path of being just another monster. What’s on screen is more maternal, which echoes Ripley and Newt in Aliens, but in a much weirder way. Ripley is not entirely human herself. She’s a being created solely to hatch this creature’s mother and then largely abandoned by her creators, who are only somewhat related to her. This alien/human hybrid recognizes itself in her far more than it does in its birth mother. The connection here is real, and Ripley’s decision to run away and abandon her child carries real weight. Not that you can blame her — Call has programmed the ship to crash into Earth in order to wipe out the aliens onboard and while Ripley isn’t big on living as she is, it’s better than the alternative. So she flees, meets the surviving gang at the escape pod and they book it out. But the Newborn has hitched a ride too. He wants his other mommy!

So Ripley can’t just run away from this thing that’s part of who she is. But she doesn’t have to accept it either. After an embrace, and with sadness in her eyes, she scratches herself and flicks her own acid blood at the pod’s window, causing it to rupture and suck the Newborn out into space through a baseball-sized hole. This is truly gruesome, the Newborn shrieking in pain as its guts are spewed through a hole as an agonized Ripley (holding on to some nearby chains) watches. Last to go is the Newborn’s head — stripped of flesh, the skull is surprisingly human-shaped. But it breaks and flies out as well.

This echoes several previous confrontations in Alien and Aliens, of course. But this time, it’s personal. Ripley already destroyed her clone sisters as an act of mercy, now she’s destroyed something she helped to create as an act of survival for others — it’s clear that Call and the remaining humans would be fucked if the Newborn lived. But it’s unclear if its life meant her death. This isn’t quite the same as the excellent “abortion” scene in Prometheus, where an alien’s “mother” frantically tries to remove the product of a rape from her body before it can kill her by being born. Ripley, an unwanted misfit, could live with this creature. They were brought into this world because their creators had specific intentions, intentions that neither wants to meet as they live according to their own plans.

But Ripley’s plans don’t include a Newborn, and the Newborn won’t live apart from her. So it has to go. But not without a final hug goodbye, and a recognition of what is being lost. And while this isn’t the most emotional separation that ends in unimaginable gore in cinema (Cronenberg’s Fly is not likely to be topped), it’s a moment of sorrow that both Weaver and the Newborn, courtesy of FX specialists ADI, make real for the brief moment that the Newborn is disemboweled by the vacuum of space, one final splurt of bodily fluids and one final change as the clone of Ripley becomes herself, not beholden to anyone she does not choose.

Whedon has spoken about his problems with the final film at length and he certainly went through the wringer working on it — going from the original concept of the heroine being a clone of Newt, not Ripley, through numerous rewrites as execs changed their minds. But it’s worth looking at his dismissal: “It wasn’t a question of doing everything differently, although they changed the ending; it was mostly a matter of doing everything wrong. They said the lines but they said them all wrong. And they cast it wrong. And they designed it wrong. And they scored it wrong. They did everything wrong they could possibly do. That’s actually a fascinating lesson in filmmaking. Because everything they did reflects back to the script or looks like something from it. And people assume that if I hated it then they’d changed the script…but it wasn’t so much they changed it, they executed it in such a ghastly fashion they rendered it unwatchable.”

One of the first things to note is the appearance of Whedon’s old friend “they said it wrong,” last seen defending a certain line about toads being struck by lightning. But look at the totality of this rejection. Everything wrong! Whedon speaks elsewhere about disliking Freeman and Dourif not for their performances per se, but because their personas are indicators of Evil and Crazy, respectively, and he thought his evil and crazy characters deserved more nuance. There’s no appreciation for what is there — Freeman’s flat lizardy menace, Dourif’s fervor and mad joy at the horrible beauty of his creation (he also does one of those prison-visitation-glass-wall kisses with an imprisoned alien. He is bonkers). The gore and violence and many chestburster penetrations in Whedon’s script — they’re all there! But they’re “unwatchable.” Look at what I gave you, Whedon is saying, and you turned out like this. You’re no child of mine.

Alien: Resurrection is the Newborn, it is Ripley. Disowned by its creators, rejected by society — the movie has become what it depicts. It’s a mish-mash of various interests that became its own thing that demands to be taken and even loved on its own terms. Dourif’s Gediman, encased in black goo and about to be eaten alive but more in love with the spawn of his awful labors than ever, hangs next to Ripley and watches the queen give birth with ecstasy, greeting the the Newborn with “You are a beautiful, beautiful butterfly!” He at least respects the essential grossness of change, the possibilities of the new, and the beauty that can come of letting the freak fluid fly.

NOTES

The pirates aren’t a one-to-one match for the crew of the Serenity but there is definitely overlap. Ryder’s petite mechanic Analee Call suggests Kaylee Frye and Gary Dourdan’s stoic second-in-command is not unlike Zoe Washburne. Michael Wincott’s sharkish captain is a cruder but still charming version of Mal. But the real tell is a tough, mean, mercenary-even-for-these-guys badass named Johner, played with assholish charisma by Ron Perlman.

And speaking of Perlman, he’s one of the few people who seems to know the exact tone to play his character in. He has the right blustery confidence to nail Whedonisms like “I’m not a man with whom to fuck!” or “Earth. Man, what a shithole.” Ryder is less successful; her default mode is aggrieved petulance. Bill Paxton’s Hudson in Aliens also whined a lot but no one really bothered with his gripes. Here Ryder is expecting to be taken seriously but unable to command attention.

“There is only HER womb and the creature inside! She is giving birth for YOU, Ripley, and now she is PERFECT!” Dourif is amazing.

I give Whedon a fair amount of crap above so some credit where it’s due. The ship’s namesake, Auriga, is a constellation, the Charioteer. So far, so straightforward. But said Charioteer is specifically a guy named Erichtonius, who was born when Hephaestus tried to rape Athena but could only ejaculate on her thigh after she kicked his ass; Athena wiped the spooge off but it grew into a baby when it hit the ground (said baby eventually became really good at racing horses). So a ship devoted to unnatural birth in a movie about men trying to force creation and the women who defy them is named after a bit of angrily rejected jizz. Pretty slick, dude.

Less slick: Jeunet originally intended for the Newborn to have extremely visible male and female genitalia. These were modeled but ultimately airbrushed out, which was probably wise for many reasons.