I grew up in the middle of nowhere. The town where I grew up has a population of around 800. Hell, it isn’t even a real town. It’s an unincorporated community. None of the town’s nearby are large either. You have to drive 50 miles to get to a town with a population that cracks 20,000, and 80 miles to get to a city that has over 100,000 residents.

I think this is a big part of why I responded so strongly to Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder as a child. Even though it was published decades before I was even born, it’s the first book I ever remember relating to.

The novel is the first of the famous Little House series. The third book in the series, Little House of the Prairie, was turned in a TV series in 1974 that ran for 9 seasons and is still beloved by many to this day.

In The House in the Big Woods, Ingalls Wilder tells the story of her early childhood, starting at age 5, when she lived with her parents, and sisters Mary and baby Carrie, in a cabin in outside Pepin, Wisconsin in the 1870s.

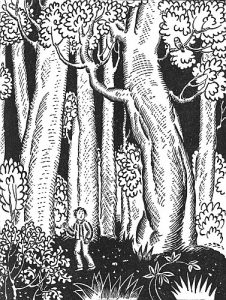

Like the Ingalls family, my family was also poor and dominated by a strong patriarch, and my memories of the past are filled with the daily struggles of survival associated with rural poverty, which were both the same as, and different from those Ingalls Wilder endured years earlier. But it also talks about the happy times, like when Pa played his fiddle at nights in the winter and Laura and Mary made playhouses under thick trees (something I also did as a child), and both the good and bad are filled with the loving nostalgia of someone grateful for the childhood that they had.

The book is filled with vivid descriptions of everyday things and special occasions. I haven’t read this book since I was a child, but so many moments are as vivid to me as if I read it yesterday.

One of my favorite passages is when Ingalls Wilder describes Laura and Mary helping their mom make butter:

“Laura liked the churning and the baking days best of all the week.

In winter the cream was not yellow as it was in summer, and butter churned from it was white and not so pretty. Ma liked everything on her table to be pretty, so in the wintertime she colored the butter.

After she had put the cream in the tall crockery churn and set it near the stove to warm, she washed and scraped a long orange-colored carrot. Then she grated it on the bottom of the old, leaky tin pan that Pa had punched full of nail-holes for her. Ma rubbed the carrot across the roughness until she had rubbed it all through the holes, and when she lifted up the pan, there was a soft, juicy mound of grated carrot.

She put this in a little pan of milk on the stove and when the milk was hot she poured milk and carrot into a cloth bag. Then she squeezed the bright yellow milk into the churn, where it colored all the cream. Now the butter would be yellow.

Laura and Mary were allowed to eat the carrot after the milk had been squeezed out. Mary thought she ought to have the larger share because she was older, and Laura said she should have it because she was littler. But Ma said they must divide it evenly. It was very good.

When the cream was ready, Ma scalded the long wooden churn-dash, put it in the churn, and dropped the wooden churn-cover over it. The churn cover had a little round hole in the middle, and Ma moved the dash up and down, up and down, through the hole.

She churned for a long time. Mary could sometimes churn while Ma rested, but the dash was too heavy for Laura.

At first the splashes of cream showed thick and smooth around the little hole. After a long time, they began to look grainy. Then Ma churned more slowly, and on the dash there began to appear tiny grains of yellow butter.

When Ma took off the churn-cover, there was the butter in a golden lump, drowning in the buttermilk. Then Ma took out the lump with a wooden paddle, into a wooden bowl, and she washed it many times in cold water, turning it over and over and working it with the paddle until the water ran clear. After that she salted it.

Now came the best part of the churning. Ma molded the butter. On the loose bottom of the wooden butter-mold was carved the picture of a strawberry with two strawberry leaves.

With the paddle Ma packed butter tightly into the mold until it was full. Then she turned it upside-down over a plate, and pushed on the handle of the loose bottom. The little, firm pat of golden butter came out, with the strawberry and its leaves molded on the top.

Laura and Mary watched, breathless, one on each side of Ma, while the golden little butter-pats, each with its strawberry on the top, dropped on to the plate as Ma put all the butter through the mold. Then Ma gave them each a drink of good, fresh buttermilk.”

Another thing I love about the Little House in the Big Woods, and the rest of the series, is how it doubles as a survivalist text. Around the time I first read this book, my dad purchased an antique muzzleloader that was identical to one he had as a child in Kentucky (my father also grew up in rural south like me before his family relocated to a Detroit housing project when he was 13), that was in bad need of a cleaning, but none of the conventional methods of cleaning he used worked. My dad was one of those people that read everything he could get his hands on, so he read The Little House in the Big Woods when I brought it home, and he used the instructions in chapter 3 “The Long Rifle” which describes how Laura’s “Pa” cleaned his gun with hot water, and used it for cleaning almost all his guns after that.

Like the Ingalls family would eventually move to the prairie, I have since moved away from my small town, but I too carry it with it.

As the book ends, “She was glad that the cosy house, and Pa and Ma and the firelight and the music, were now. They could not be forgotten, she thought, because now is now. It can never be a long time ago.”