In the 1950s TV couldn’t hope to replicate the theatrical movie experience. But it made up for inferior quality with convenience and bulk, the two characteristics of many successes in American innovation. The movies struck back by continuing to be the movies, only more so, luring audiences back with more color pictures and eventually making widescreen the default. In 1952 an eager early warrior against audience leakage debuted: Cinerama.

Cinerama was the brainchild of inventor, boatsman and ski enthusiast Fred Waller. In its purest form Cinerama used three projectors to show a widescreen image on an enormous curved screen with a surface made up of hundreds of thin vertical strips angled to face the audience. The process of filming and projecting in Cinerama was expensive and unwieldy, involving a triple-camera-single-shutter rig for the filmmakers and a proprietary projection and surround-sound system for the distributors. The projector included magnificent devices like the “Gigolo,” their word, which jiggled at the edges of the film in a not always successful attempt to smooth the seam between the projected thirds.

Details of the process and history of Cinerama are beyond our ironically narrow scope today. Instead we’ll try to recapture the thrills of experiencing This is Cinerama, a spectacle intended to demonstrate the prowess of the revolutionary Cinerama process. Today only three places exist on the planet to experience the true thrill of the Cinerama process, most of us will have to make do with the bastardized version of the film available on Blu-Ray and streaming that uses “Smilebox” formatting that expands the letterbox at the edges– like remapping the film over a Budweiser logo – to correct the perspective lacking a giant, concave screen. Having read the dubious accounts of early cinema-goers diving out of the way of trains on the moving picture screen, and personally experienced the box office phenomenon of the immersive digital world of Avatar, I pulled my chair up close to the Smileboxed screen, cranked up my sound system (a meager 2.0 setup, fully 5 tracks short of true Cinerama surround) and eagerly anticipated that which blew bleeding edge cinephile minds halfway between Lumière and Cameron.

After a four minute orchestral overture, the center of the curtains covering our bowed viewing area parts and we get a 4:3 black-and-white address by Lowell Thomas, one of those welcoming videos from the 1950s that takes place in a mahogany room with a giant map on the wall. Thomas traces Cinerama’s origins all the way back to a cave drawing of an eight-legged boar. At twelve minutes, it is a quite thorough presentation. It also, without giving away a frame of spectacle, suggests the scale of Cinerama as something that encompasses prehistoric, Renaissance, and motion picture history. We came for big movie pictures and now discover we’re witnessing a 20,000 year culmination of evolution. Anticipation runs high.

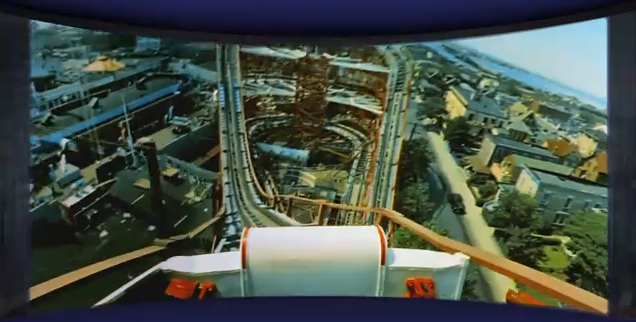

Suddenly, before the curtains can even dash outward to the new sides of the frame, a color film taken from the front of a roller coaster car stretches across the bow-tie shape of the screen. Having spent the last quarter hour having the senses recalibrated by mono sound and a dull picture, the sudden expansion in space and sound packs a wallop even in my compromised setup. Scaling up for the intended size, one can believe the report of “the shrill screams of the ladies and the pop-eyed amazement of the men” on the front page of the New York Times following the premiere.

After the roller coaster ride we watch a static wide of ballet performance, showing off Cinerama’s high art applications, and then a view from a helicopter over Niagara Falls. A choir singing Handel’s Messiah emphasizes my 2D sound setup, as the choir sings their way to the risers while passing the camera on either side, no doubt taking advantage of the missing sound channels to create a surround sound effect. But even on two speakers it’s clear the sound innovations are what hold up the best seventy years later (though much of this had been pioneered by Disney’s Fantasia project about ten years before Cinerama).

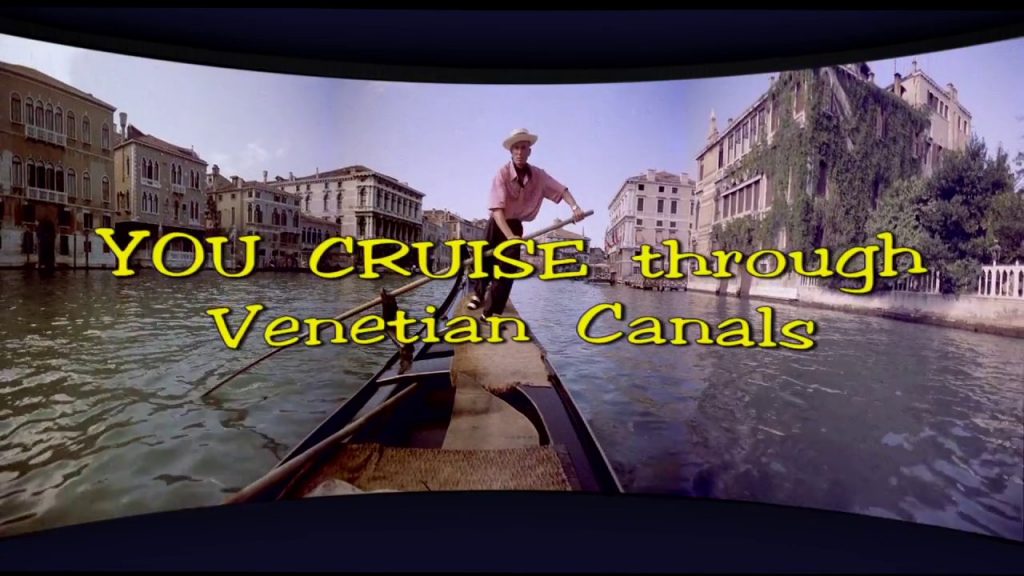

Thomas returns and it turns out his office walls are an ugly teal. He introduces what would prove to be the dominant category of Cinerama filmmaking, the travelogue. We’re invited on a tour of the world (well, Europe). We visit Venice, where we can take in the view from a gondola. We are subjected to a bagpipe parade in Edinburgh with no escape. We can count costume threads at the opera in Milan, see clearly the faces of looky-loos staring at the cumbersome camera rig at a bullfight in Madrid, detect testicles descending in the voices of the Vienna Boy’s Choir.

The second half moves the tour back to America, kicking off with a lengthy section in Cypress Swamps of Florida. The Cypress Swamps offer tranquil boat rides past beauties in Antebellum outfits, though the immersion is somewhat spoiled when the soundtrack is goosed with Australian kookaburra calls, the default sound of movie wilderness. Then the Southern ladies strip down to swimsuits and some hunks emerge from the water, perhaps eliciting more pop-eyed amazement from the mid-century audience, accounts are silent on the matter. We’re treated to a front row seat to a spontaneous waterski exhibition, as all three Waller obsessions combine.

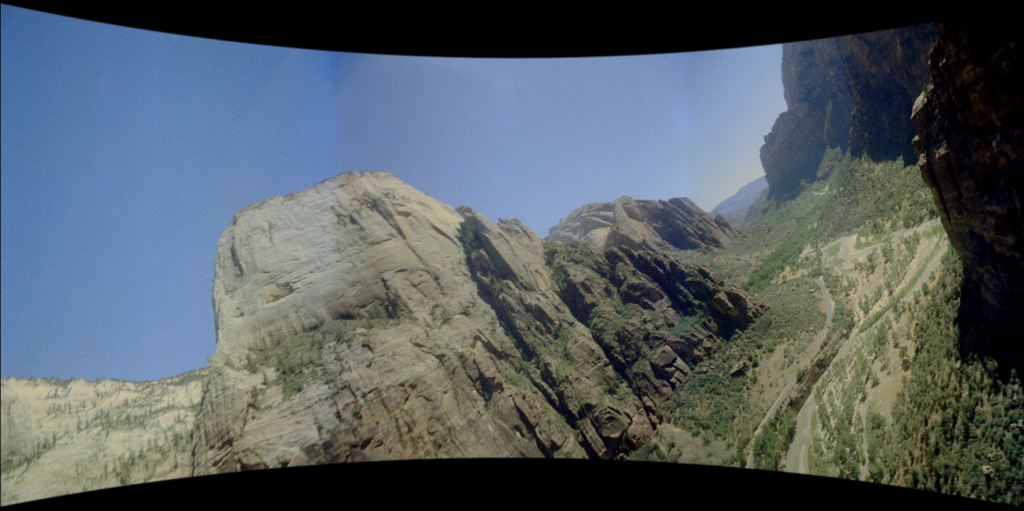

The film’s big finish is an aerial tour of the United States over the skyline of New York, across the plains of the Midwest, all the way under the Golden Gate Bridge. I’m as big a fan of fruited planes and purple mountains majesty as anybody but I’m also a fan of musical variety, and making a gentle travelogue sound like the climax of a fireworks show gets tiresome after an hour. Between the grand orchestral arrangements and choral performances you get the sense of how the pissant electric guitar would soon upend things for the mahogany and map crowd.

And that’s all, folks, please exit into the future.

Part of the modern wonder of Cinerama is the near impossibility of seeing it as intended. “Much of your perception of reality depends on your vision to the side, though you may be hardly conscious of it” Thomas informs us, but unfortunately sitting close enough to put the sides of my screen into my periphery also puts me close enough to see the digital artifacts of streaming (I used Kanopy to watch). Though many of the benefits have to be imagined, the small screen translation preserves the limitations of the process. The digitally-matched seams between the sides are smoother than reported in proper triple-projector screenings, but variation in film stocks (or preservation of their negatives) still makes the transitions between each third visible, especially across uniform blue skies. The handoff between screens can create disorienting effects like one half of the Messiah choir experiencing a minor earthquake while the other side stands solid, or a smudge on one lens doesn’t carry to the next portion of the picture. Not terribly distracting at home but probably tough to ignore when the artifact is a couple stories tall.

Thomas’s office also hints at the issues that bothered traditional cinematic storytelling, as he moves from a looming El Greco figure on the right side of the screen back to a reasonably proportioned presenter in the center.* This would have been mitigated by sitting in a theater with the curved screen – if you were fortunate enough to get a seat within the optimal viewing area. Also, Cinerama filmmakers found that actors sharing the screen had to look at calculated points for dialog because when looking at each other on set their eyelines wouldn’t line up in the curved final product.

Since staring at co-stars who aren’t there wouldn’t become standard until digital filmmaking, it’s not surprising that Cinerama only produced two proper narrative films: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and (most of) How the West Was Won. A handful of films – starting with It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and resurrected for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight roadshows – used a single-strip 70mm filming process under the Cinerama name which was easier to manage and less expensive relative to burning triple the amount of film stock per shot. The giant picture, precise surround sound, eventually watered-down brand point to IMAX (especially domed screens usually showing nature or travel fare) as it descendants. But the ungainly technical burden for mixed returns also makes it an ancestor to Ang Lee’s experiments in high frame rate like Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk and Gemini Man, films whose format also posed such problems for the exhibitor they will rarely or never get seen as intended.

The most striking takeaway of This is Cinerama is what constituted spectacle in 1952. In the pre-Laser Age of This is Cinerama there’s no special effects shots, no trips to outer space (18 years later 2001: A Space Odyssey would amaze audiences with the watered down single-camera version of Cinerama). There’s not much demonstration of cinematic language displayed in silent films during the prologue. The Cinerama camera rarely cuts in continuity. It moves if it can be attached to a vehicle, like the roller coaster or a boat, but otherwise the camera remains perfectly static, giving us uninterrupted shots of Aida and the choirs. For all the innovation on display it actually resembles the earliest experiments in motion pictures and their attempts to capture live performance. We get less a cinematic experience as we know it – where the camera and editing are full participants in the effect – and more like a visual equivalent of an audiophile goal, chasing perfect replication of the original moment.

Cinerama’s time passed quickly but it was at the forefront of the popularization of widescreen. It presaged the 3D strategy of the early 2010s, another attempt to fight video competition at home by offering more sensation. If nothing else, any time something’s enormity is described with the suffix “-orama,” Cinerama’s legacy lives on.

* For the sound mix nerds, his audio pans with him, right to center, an early example of a brief era when dialog was sometimes placed in the stereo mix to match the speaker’s position on the screen (some mixes of Lawrence of Arabia do this, I think) before it was noticed that swapping a character’s audio position causes a lot more viewer whiplash than suddenly moving his screen placement with a cut.