Once an eager young upstart working for a Sydney television station, Peter Weir is now a six-time Oscar-nominated director responsible for some of the most memorable American films of the late 20th century. With Dead Poets Society and The Truman Show in particular, Weir wrung sensitive performances from known comics by daring them to go beyond their comfort zones. He also made no small name for himself at home in Australia: in 1975, he directed Picnic at Hanging Rock, the period horror film that breathed new life into the long-dormant Australian film industry, and in 1981, he dramatized the Anzac legend so central to Australia’s nation-building mythology in Gallipoli.

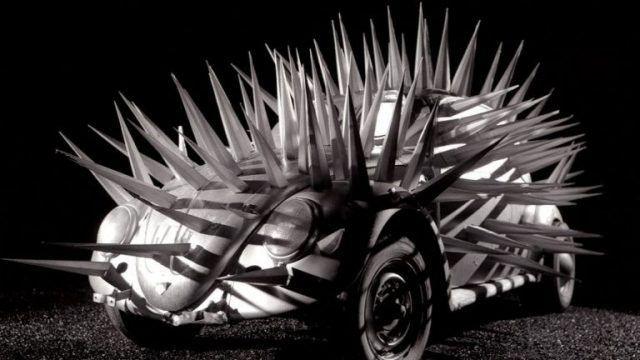

Before all of this, there was The Cars that Ate Paris (known stateside as The Cars that Eat People). Casual fans of Ozploitation will no doubt see the title and the 1974 release date and imagine the worst (read: best) — a gloriously gory and nastily cheap tale of carnivorous, anthropomorphic muscle cars in Australia’s heterotopic outback. Yet Weir’s debut feature is ostensibly more measured than you’d imagine (and somehow it has even less plot). The Cars that Ate Paris is instead a supremely Gothic mood piece that is much more in line with Picnic at Hanging Rock than, say, Body Melt. Instead of the outback desert, ever a common setting for Australian horror, it’s set in a pastoral landscape like the ones you’d see in a Frederick McCubbin painting.

The story takes place in the titular Paris, which seems to be a popular route for passing travelers. Unfortunately, these travelers invariably crash their cars and die when they reach the little township. The wreckage is then stripped for parts and used as a kind of currency. When two brothers are thwarted by Paris’ roads, one survives, though he’s too traumatized to drive again; he’s therefore trapped in this mad little town somewhere in the bush, languishing in this sublime, prison-esque nether region where the denizens’ behaviour grows increasingly bizarre with each passing day. Through Arthur’s eyes, we see a town governed by car culture, toxic masculinity, experimental medicine, and, to be honest, very little else.

In a way, The Cars That Ate Paris is like an earlier version of Mad Max in its perspective on car culture. It forms a weird double bill with another Australian release from 1974, Stone, which is essentially Easy Rider if that movie had been about beer and fighting. The Australian film industry at that time was under pressure from the federal government — which, then as now, funded Australian filmmaking — to create a national image of Australia for international audiences. In this, they expected films like Gallipoli and Crocodile Dundee; what they didn’t expect were films like the sweat-drenched Wake in Fright or the titty-laden Adventures of Barry McKenzie. The Cars That Ate Paris falls easily into this latter camp, although its criticism of car culture is certainly less scandalous than the other films mentioned.

Ultimately, Cars’ biggest setback was its inability to find an audience. Even today, audiences struggle to decide whether this is an art film or a horror film; in 1974, the distributors simply threw it at audiences, and it took them six years to recoup even half of the budget. Indeed, Cars remains underseen today, which is partially because it’s regarded as a curio; an origin story in Weir’s brilliant career. Being honest, I would also regard it as a curio, although less so from the perspective of authorship than of Australia’s cultural history. As a snapshot of an industry in flux, it’s almost unrivaled; within the film, you can almost see the tug and pull of the Australian film industry which, at that time, couldn’t decide if it wanted to fund money-making entertainment or “respectable” art cinema. Cars goes for both while addressing the question of national image in its own twisted way.