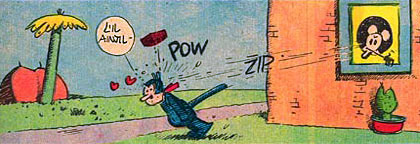

You probably know George Herriman’s Krazy Kat: the newspaper comic strip that forward-thinking critic Gilbert Seldes called “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today” in 1924, and which years later was named the number one comic strip of the twentieth century by The Comics Journal. Set against a stark desert landscape, Krazy Kat rang changes on a love triangle between the androgynous title character; Ignatz, the brick-throwing mouse who rejects Krazy’s advances; and Officer Pupp, the authority figure forever throwing Ignatz in jail. Herriman’s surrealistic landscapes, boldly inventive page layouts, wordplay, and homespun philosophizing stood out amongst the strip’s newspaper peers and have influenced later creators as diverse as Bill Watterson, Patrick McDonnell, and Brandon Graham.

But there is another Krazy Kat, much less well-remembered: almost from the beginning of the strip’s newspaper run, Krazy and Ignatz were licensed for animation by King Features Syndicate and passed through several studios’ hands in over two hundred shorts. Herriman had nothing to do with these cartoons, and it didn’t take long for them to take on their own character under the influence of prevailing trends in a crowded marketplace. By the time Charles Mintz had the license in the 1930s, the animated Krazy barely resembled the original beyond the white bow around his neck. Instead of the boxy, sketched-in design Herriman drew, this Krazy had a round head and big eyes, wore white gloves, and instead of dwelling in an expressionistic desert, was a firmly urban kat, hustling to make a living. In short, he was of a kind with the animal leads of the black-and-white “hosepipe” animation era: Felix the Cat, to whom Krazy has a close resemblance; Betty Boop’s dog pal Bimbo; and, of course, Mickey Mouse.

Of the Mintz Krazy Kat shorts I’ve seen, most follow a familiar formula: Krazy is in a situation, perhaps trying to accomplish a task or working a job; a series of gags and complications unfold, generally related to the setting; things get out of hand; it all builds up to a climactic chase sequence, or maybe an explosion; the end. There may also be some caricatures of current movie or music stars thrown in, a device now mostly associated with Warner Bros.’ Looney Tunes. Most of these “Krazy” kartoons are pretty blah.

But there is one Krazy Kat short that rises above this forgettable mediocrity: 1935’s “The Hot Cha Melody,” directed (as were all the Mintz Krazy Kats) by Manny Gould and Ben Harrison. I don’t know why this one is so much better than its fellows: perhaps it has something to say, or perhaps it’s given energy by the title song, threaded through the story; maybe Gould and Harrison just knew they had a good premise and worked it to the hilt. All I know is that when I first watched it, I cackled; I felt ebullient; I was filled with the same wonder and delight I experienced watching “Bimbo’s Initiation” or “Betty Boop, M.D.” for the first time, the sense of “I can’t believe this—where will it go next?”; indeed, “The Hot Cha Melody” is one of the few Krazy Kats that holds up to a comparison with the Fleischer studio’s masterpieces. To paraphrase Homer Simpson, I don’t want to oversell it, but it was better than ten Super Bowls.

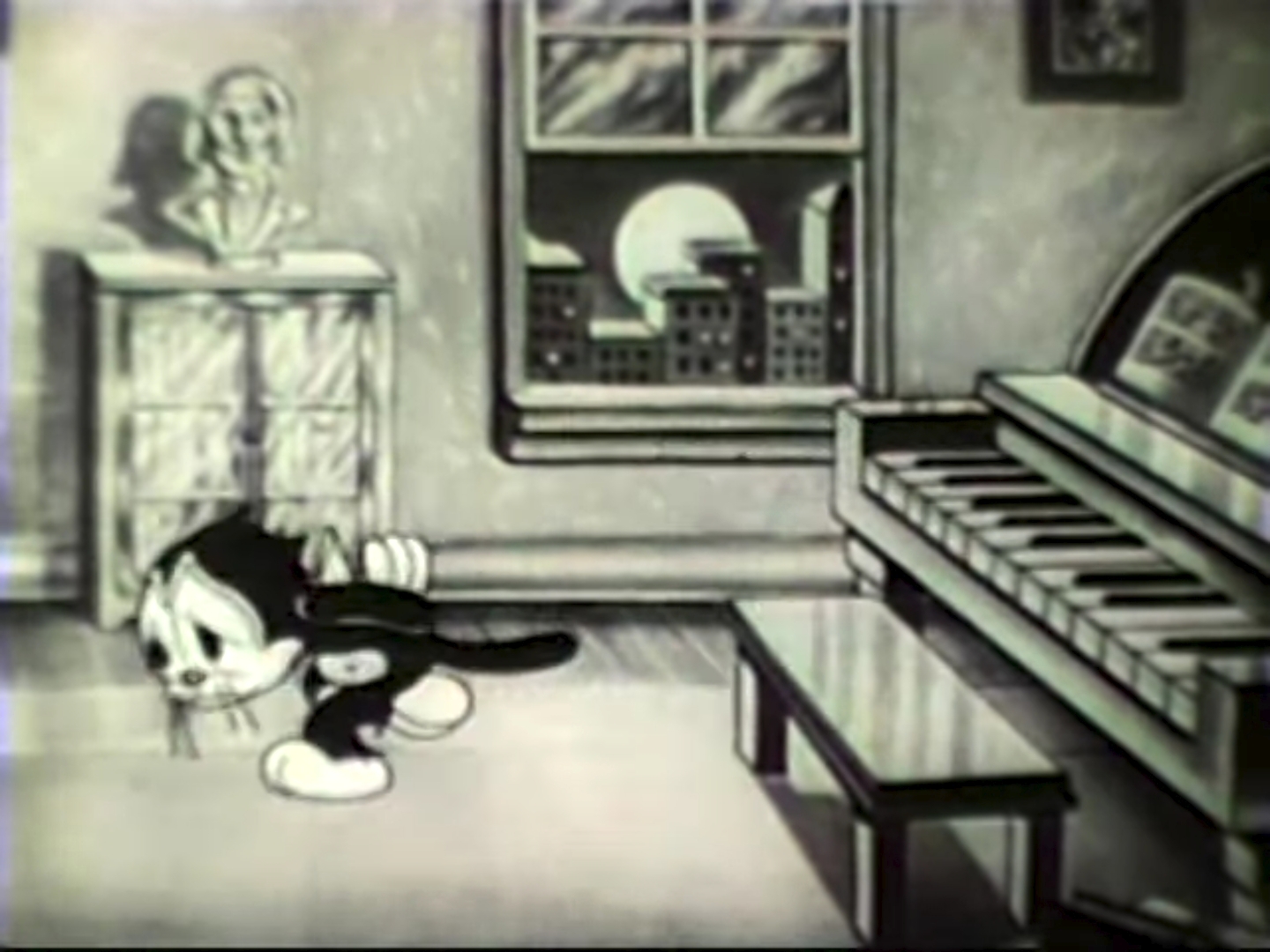

“The Hot Cha Melody” begins in Tin Pan Alley, the heart of the music publishing industry: in establishing shots, aspiring songwriters crowd the doorways of publishing houses, push wheelbarrows full of sheet music down the street, and joyously celebrate the musical gold rush. In adjacent studios, working songwriters shamelessly copy from one another, churning out identical ditties with only the words changed. Krazy Kat, in his own studio, listens in and rejects that kind of naked commercial grab. Trying to come up with something original, he paces until he wears a literal hole in the floor and racks his brain until the gears inside grind and collapse in failure.

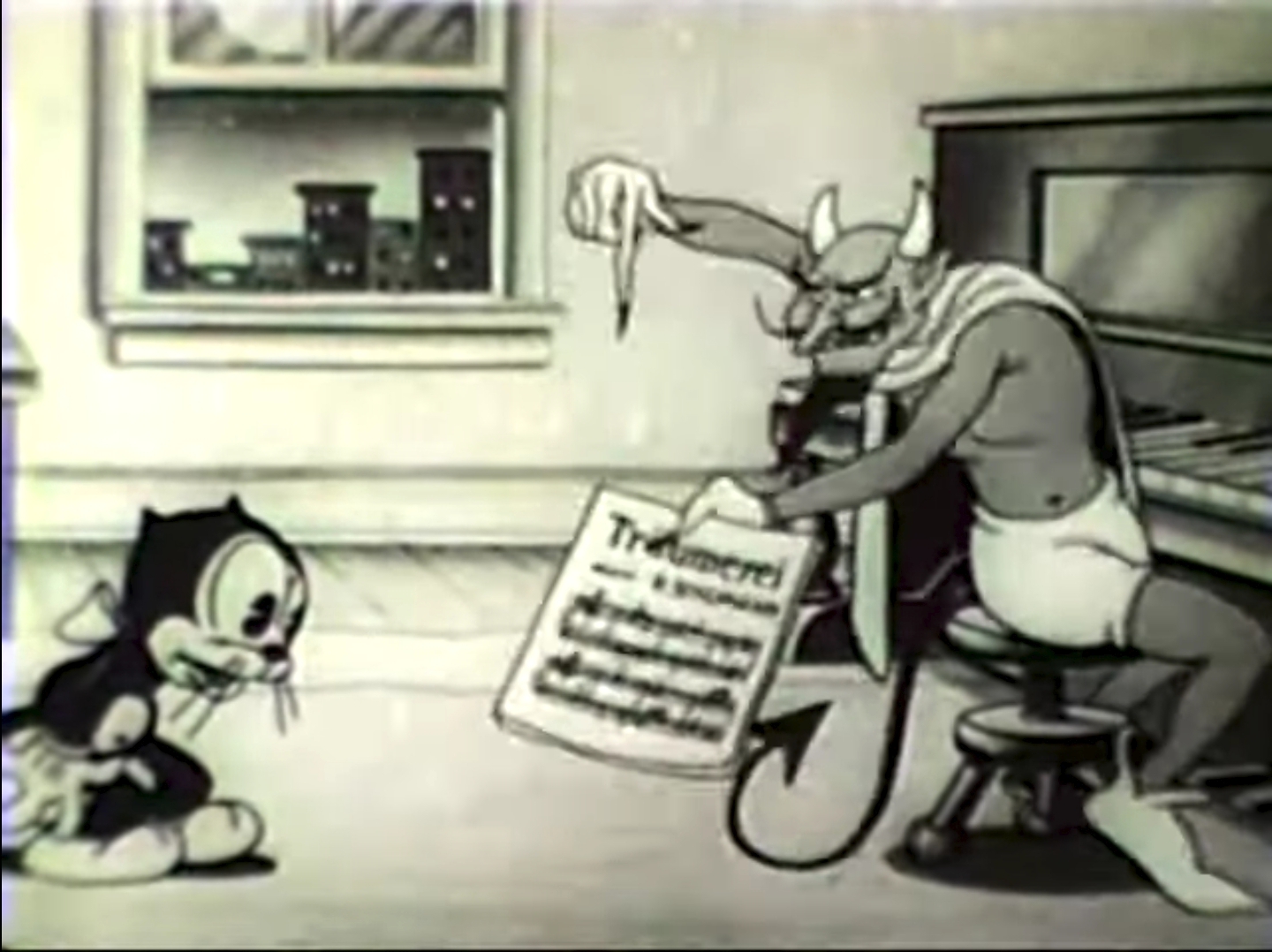

Summoned by his frustration, the Devil appears and offers a tempting solution: “Don’t be a fool—steal!” Krazy resists, but the Devil keeps pushing, producing a copy of Robert Schumann’s 1838 piano piece “Träumerei”; he plays the opening passage. Then, despite Krazy’s chiding, he opens the piano and reveals a sort of musical typewriter; he begins playing a jaunty, barrelhouse version of the “Träumerei” theme as the piano types up his “new” composition, and he sings: “Oh play that hot cha melody, it’s such a hypnotizing, tantalizing, strain!” It is hypnotizing, because in no time at all it gets Krazy’s feet tapping and he starts singing and playing along. Krazy’s boss, the head of the Smash Hit Music Co., hears the song from out in the hall, likes what he hears, and declares, “It’s stupendous! It’s colossal! It’s a hit!” while the Devil sneaks away with an evil laugh.

Outside, the Devil stalks toward a statue of Robert Schumann in a park; he opens the base of the statue to reveal a radio playing the new hit song. The ghost of Schumann, emerging from the statue, listens in shock and cries, “Ach! Mein musik!” The ghost heads back into the city to find the source of this desecration, and is stunned by bright signs everywhere advertising “The Hot Cha Melody.”

Meanwhile, in his studio, Krazy enjoys his newfound success, surrounded by radios, each playing a different version of the song while caricatures of then-current artists emerge from the radios in turn: Bing Crosby, Rudy Vallée, the Boswell Sisters, and Kate Smith. The final tap dancing, scat singing radio seems to combine Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Cab Calloway into one figure, but instead of a specific caricature like those given for the white artists (including Schumann), it’s a much broader cartoon in generic minstrel blackface, a regrettable example of the racist imagery that was often taken for granted in cartoons of the ‘30s. (In fact, not to digress too much, but there is a straight line from minstrel shows to the black-bodied, white-faced cartoon characters of the era, a connection gradually erased from public memory in later years. See David Wondrich’s article “I Love to Hear a Minstrel Band” in The Cartoon Music Book.)

Schumann sweeps into the studio, destroying the radios, down to the last hot-cha-ing vacuum tube. Rounding on Krazy, the ghost accuses: “You stole my melody! You stole my melody!” and (typical cartoon ending here) chases Krazy into the innards of the piano/typewriter contraption, where Krazy is knocked silly by the hammers while Schumann plays. Despite this punishment, Krazy smiles, because success is the great justifier: “It’s a hit!”

To begin with, it’s rich for this Krazy Kat, so derivative of other funny animal cartoon characters, to be set up as a tortured artist, striving for originality. Herriman’s newspaper Krazy has sometimes been read as a metaphor for the artist as romantic dreamer, with Ignatz as the Philistine public, throwing bricks of mockery or indifference. But the animated Krazy left that behind when he got a day job, and it doesn’t take very long for him to give in to the Devil’s offer. In fact, Krazy is a passive participant in this particular cartoon, less acting than acted upon, unless one takes the defensible position that the Devil and Robert Schumann aren’t literally present but stand in for warring sides of his own personality, the temptation to take shortcuts and the urge toward deep, personal expression, respectively.

In that sense, Schumann is an excellent choice to represent the latter impulse: the composer was one of the early Romantic era’s foremost exponents of “art for art’s sake;” in fact, it was he who coined the term “Philistine” to refer to the uncaring, ignorant public. Schumann also suffered from anxiety and mental illness, spending the last years of his life institutionalized and suffering from delusions and auditory hallucinations. He himself believed that he was being haunted by the spirit of Carl Maria von Weber, a composer from the previous generation whom he idolized. I have no idea if the makers of “The Hot Cha Melody” were aware of those associations or chose to play upon them, but the idea of Schumann as a vengeful spirit, aghast at what a later generation had done with his music, is grimly appropriate.

Of course, Schumann’s music was tuneful and popular enough to be ripped off: cartoons and popular culture in the early decades of the twentieth century made much of the divide between “classical” and “popular” music, but there was naturally a great deal of crossover. The former was respectable and synonymous with education and taste, but could also be stuffy and pretentious; the latter was seen as trashy and amateurish, even dangerous (especially in racially-potent ragtime and jazz), but was also lively, fresh, and authentically American. Just as borrowing and quotation were longstanding practices in classical music, “longhair” melodies were often appropriated for pop styling: “ragging” or “jazzing” the classics was a genuine phenomenon, satirized in “The Hot Cha Melody.” For example, Raymond Scott, whose music would become associated with cartoons through Carl Stallings’ arrangements, reworked a Mozart piano theme into “In an Eighteenth-Century Drawing Room.” Bassist and bandleader John Kirby, sometimes dismissively referred to as “the black Raymond Scott,” answered by titling a composition “20th Century Closet,” but he also played the game, turning the slow movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony into the jumpy “Beethoven Riffs On.”

Finally, there is the ending, one of the most pointed I can think of from the era. (I love them, but let’s face it: most cartoons from the 1930s keep running until they hit a wall, and sometimes end without conventionally resolving a plot at all. As an organizing principle, the gag reigns supreme.) 1935 was the depth of the Depression, and it’s instructive to compare Krazy Kat to his competition: Betty Boop and Bimbo often appeared down on their luck in the cartoons of the mid-‘30s, but they’re cozy; they have each other. Even in poverty, Betty comes off as a Cinderella whose good qualities shine through, and ultimately perhaps the best things in life really are free. Krazy, on the other hand, doesn’t have the luxury of being beloved; being number two (or number three), you really do have to try harder. To bring things back full-circle to comic strips, a 1982 installment of Matt Groening’s Life in Hell is titled “The Los Angeles Way of Death”; each panel illustrates a way your story could end in L.A., simply labeled “Gun,” “Car,” “Drugs,” et cetera. The last two panels, labeled “Failure” and “Success,” are identical, with the strip’s hero Binky stuck behind a desk in an office, the direction of the productivity chart behind him the only difference. That seems to be the position Krazy takes at the end of “The Hot Cha Melody”: if you’re bound to suffer in life, why not do so cushioned by easy money? A hit is a hit.