The major and most common mistake made in today’s blockbusters is handing over million dollar franchises to inexperienced directors. Colin Trevorrow had directed exactly one feature film before Jurassic World, an indie comedy almost completely devoid of special effects or action scenes called Safety Not Guaranteed; by contrast, Steven Spielberg had made five films before Jaws (three of which were suspense stories) and fifteen before Jurassic Park. It’s not an insult to say Trevorrow never had a chance of living up to the original film because Spielberg himself, at the same point in his career, could not have lived up to it. That said, Trevorrow had an actual roadmap for a good dinosaur film in front of him, and instead of learning form the past, he awkwardly recreated elements of the original film while either missing the point or failing to stick the landing; I think it’s worth going back to the original and seeing what made the thing work.

DIVERSE MORALITY

An underrated element of an enjoyable story is a diverse set of viewpoints; of the three scientists in the film, only Grant and Sattler share a knowledge base, and where Grant has an ironic aloofness (and hates children), Sattler has sincere warmth. Each character has things they and only they would do, and it gives each scene a chemistry and power depending on who’s in it; Sattler will gently poke at Grant’s aloofness where Malcolm will unthinkingly run roughshod over it, and when Sattler and Malcolm share a scene he gently flirts with her by trying to impress her with chaos theory. Each and every scene is a journey, never mind the film.

EXPOSITION IS AN ACTION

Act One of the film is a constant wave of exposition, laying out everything from the park’s various technical problems to Grant’s occupation to the intelligence of the velociraptors. But even when it literally railroads characters through exposition, it’s never just expositing – the way the information is shared and received becomes both plot momentum and character beats. When we meet Grant, he owns a snotty kid by scaring him with information on velociraptors, teaching us about Grant’s authority as a dinosaur expert, his respect for dinosaurs, his hatred of children, and, oh yes, we learn a thing or two about velociraptors. Each and every scene has this elegance and deceptive simplicity, and it pays off best with John Hammond.

For all Richard Attenborough’s sincere niceness, it’s clear that Hammond has a big sense of entitlement and expectation that people see the world the exact way he does; he’s introduced helicoptering into Grant and Sattler’s digsite, risking ruining the dig, and walking straight into their kitchen and opening their champagne, and it’s only his offer to fully fund their dig for three years that they come around on his request for help. When he shows them the park, he hadn’t anticipated the paleontologists might be interested in seeing the dinosaur eggs in intimate detail, and this doubles as laying down plausibility for the park shitting itself and as doing the same for the team’s quick-thinking when it all goes south.

(At the same time, his pleasure at showing them the wonders of a dinosaur egg hatching keeps him, if not sympathetic then at least likable)

OUT OF THE FRYING PAN, INTO THE FIRE

Blockbuster adventure films, as opposed to tragedies or character studies, really only have two acts: an expository opening act leading up to the premise, after which it’s simply the characters getting out of one bad situation and into another – Back To The Future worked under that structure, as did Spielberg’s earlier Indiana Jones movies. Spielberg has much, much more patience than many modern filmmakers; his suspense sequences feel like they go nearly twice as long as more modern movies, and in fact I can feel where a weaker filmmaker would intercut two sequences. Spielberg doesn’t give us any relief from the tension; in fact, the only sequence that intercuts two areas of the island is where Sattler is reactivating the power while Grant and the kids are climbing an electric fence, increasing the tension.

DON’T FAKE EMOTION

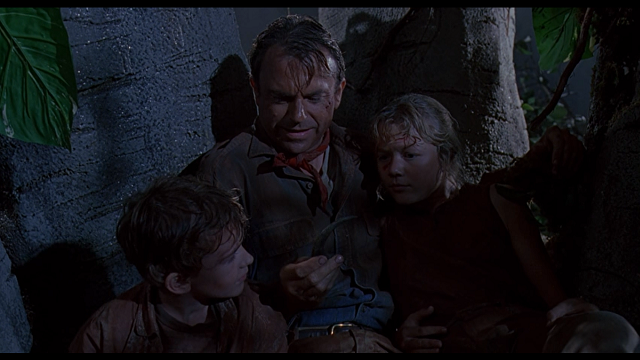

There are two scenes that tend to strike fans as surprisingly emotionally tender for a film about people getting eaten by dinosaurs: when Hammond tells Sattler about his flea circus, and when Grant talks to the kids in the tree while watching the brachiosaurus herd. I’ve seen many movies where the director was clearly thinking, if not of those scenes specifically, of creating in their audience the same vivid emotional response; there are scenes where you can almost hear the director whispering in your ear, “Okay, now this is the sad bit! Cry! There’s the thinky bit, think about man’s inhumanity to man!”

These scenes are different. They come at a lull in the action when the characters would plausibly have both time and inclination to think and reflect, and they both fit into the character’s overall journeys; Hammond’s flea circus monologue is one last attempt to justify the park before he finally recognises what he’s done, and Grant’s scene with the kids is when he stops being irritated by their presence – after this, he’ll make a joke with them he never would have done before.

If you like, weaker directors make the same mistake as Hammond, thinking they can control and railroad the emotional reaction of their audiences. Spielberg simply presents a story, and while he’ll use every tool at his disposal to sell it – he reminds me of James Cameron and stands in stark contrast with Quentin Tarantino in that everything, from framing to acting to music, complements rather than contradicts each other – he’ll just let it play out in front of you.