Before his career became defined by the twin pillars of The Deer Hunter and Heaven’s Gate, the late Michael Cimino announced his promise with a wonder of a debut: the loose-limbed, deceptively modest Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, an assured mix of genres and tones starring Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges as the titular unlikely partners in crime. They are brought together in the opening minutes: the aging thief who’s been laying low in Montana after a robbery that left him as the only person knowing where the money is hidden, and the driver of the stolen car in whose passenger seat the older man winds up while running for his life from a homicidal former accomplice.

They are from different generations and of different attitudes: one wary and cautious, with that Eastwoodian steely glare, the other shaggy-haired and excitable, looking just the right age to have gotten caught up in the counterculture a few years earlier and left with no direction afterwards. But both are drifters and alone, and soon enough a connection forms — especially on the part of Bridges’ Lightfoot, who has finally found someone or something he can attach himself to. Going in search of the aforementioned loot, they get chased and, eventually, ambushed by two of Thunderbolt’s former partners, Red (George Kennedy) and Eddie (Geoffrey Lewis), the former of whom is as vicious as the latter is pathetic; not finding the cash where it’s supposed to be, the four eventually team up to commit the exact same heist again. For Lightfoot, who pushes the idea forward, it feels like a no-brainer; but a certain wistful irony of trying to repeat something that didn’t do anybody any good the last time is not lost on the film as a whole.

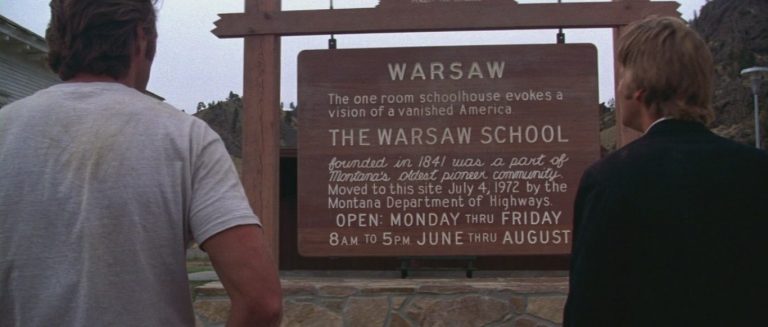

Cimino wrote, and titled, the film as an homage to 1955’s Captain Lightfoot, Douglas Sirk’s rousing Technicolor adventure about the swashbuckling exploits of 19th century Irish rebels; like his subsequent New Hollywood works, the director’s debut is singularly marked by an attempt to combine the dazzling widescreen grandeur of the pictures of his youth with the weariness and fatalism of the 1970s. In Sirk’s film, the nicknames adopted by the characters implicitly served as a weapon, a source of power, a way of becoming mythic and reaffirming their allegiance to a struggle greater than themselves. In Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, they’re all the protagonists have (we never learn their actual names); these are misfits lost in a country that’s left them behind, their physical struggle petty and ugly — they bicker and fight amongst themselves, the police showing up only briefly and as a faceless force — and their existential struggle absolute. In their chosen outlaw path, the film locates both unspoken desperation and — most notably in the scenes where they’re forced to pick up odd jobs in order to be able to buy tools for the robbery — awkward comedy, but never exactly triumph. Performance for them is a means not just of getting rich, but of survival, of escape — and also, perhaps, in one specific case, of revealing what they can’t say.

The contradictions are reflected in the film’s use of locations, the magnificent Big Sky Country landscapes — sometimes almost too painterly to be real — alternating with dark alleyways and cramped trailers, the protagonists looking to the former but often having to operate in the latter. The dynamics between the characters, for their part, occasionally seem to mirror those offscreen, which were instrumental to making the movie what it is. When, in the climactic robbery sequence, Kennedy’s Red urges Thunderbolt to take more money from the Western Union vault, the latter instead prefers not to tempt fate and get out sooner, which brings to mind Eastwood’s own directorial and producing style; on the set, he kept Cimino’s already notorious perfectionist tendencies in check, indulging him only rarely, and this firm guidance may well have ensured, or at least contributed to, how purposeful — and thus natural — the film is in its classic ‘70s shagginess. Meanwhile, one can glimpse the director himself in Lightfoot, a talented young dreamer enabled and ennobled by his more seasoned collaborator, filled with ambition and energy that may not always serve him well.

Still, that description doesn’t touch on the one unexpected, and crucial, part of the character: that, at a certain point, his reverence for his older partner has unmistakably grown into something more like infatuation, even attraction. This is never explicitly acknowledged in the dialogue, but Bridges — whose performance is a heartbreaking marvel, up there with his very best work — doesn’t need any to convey it, while Eastwood, whose stoic exterior has rarely masked this much understated warmth, responds by playing Thunderbolt as someone who senses this feeling and doesn’t reject or discourage it, but seems even less equipped to actually respond to it.

This unarticulated tension, which takes the familiar buddies-on-the-road dynamic into actual doomed-lovers territory, underlines Thunderbolt and Lightfoot as a rare beast: the ‘70s American crime movie made by a romantic. In making the genre his own, Cimino couldn’t go any other way than to imbue its ironies and its ruthless twists of fate with a melodramatic weight; the charismatic outsiders who are his heroes are defined by being just smart and capable enough to stand a chance, but not quite enough to deal with all the obstacles in their way, — especially other people with much less left to lose. They don’t simply pursue; they yearn. This yearning permeates the film, a small epic that stands its ground, today, as a more successful work from its director than both of the actual epics that followed it.