It begins with a close-up of the stage floor, a streak of light cutting vertically through the frame. A shadow of a guitar neck fills it for a second before being swallowed by a larger shadow of the man holding it; then his shoes—the first physical representation of him—enter the frame and are followed by the camera towards the microphone. He places a boombox on the floor, cheekily announces that he has a “tape I wanna play,” and gets to work on “Psycho Killer” as the camera slowly rises from his feet tapping on the floor to reveal his face just before he starts to sing. These are 45 seconds within an unbroken two-minute opening shot where each newly introduced element builds on the one before it, and together they create the sense of a void starting to be filled—a sense reinforced by the very first cut: from the close-up of David Byrne to a wide shot of him with his back to the camera. The audience is mostly indistinguishable here, Byrne’s light gray suit looking bright against the murky auditorium, while behind him the warehouse-like stage is massive and mostly bare, a dead space where he stands as the only active source of life. Obviously this won’t do, and it scans as an implicit response when Byrne ends the number by leaving the mic to stagger all over the place, jamming on his guitar, while a technical crew brings out some actual equipment.

Enter the great Tina Weymouth: already on the stage when the camera finds her, bass in hand, grinning and ready to go, all in direct opposition to Byrne’s methodical reveal. Contrast is important to Stop Making Sense, and Byrne and Weymouth complement each other through their contrast: a dark-haired, angular, anxious-looking man in a sharp suit and a sunny, relaxed blonde woman in a baggy house painter’s getup (“he’s bones, she’s flesh,” Pauline Kael sums it up in her contemporaneous review). The first two songs themselves are significantly different, too, and so director Jonathan Demme, DP Jordan Cronenweth, and editor Lisa Day shift the presentation accordingly: where the jagged, staccato beats of “Psycho Killer” were subtly underlined by a mixture of slow zoom-outs and hard cuts between unpredictably shifting POVs, the focused melancholy intensity of “Heaven” gets augmented by a series of lulling, delicate dissolves between medium and wide shots that tend to include both band members.

The gradual introduction of Talking Heads and their instruments means an opportunity for the film to build and shake things up both visually and aurally, not just treating newly arriving people and their equipment as elements of visual interest but actively responding to what they bring. Once drummer Chris Frantz is up onstage, Cronenweth’s camera spends the first minute of “Thank You For Sending Me An Angel” doing a semicircle around him, casually observing him in action, its slow movement counterbalanced by the energy of the song. This intro over, Day seals the deal by cutting to the closest thing the film is going to have to a recurring image: Byrne in gray clothing standing just off-center in front of the mic, Frantz in a teal polo shirt working the drums behind, above, and to the side of him. This is an obvious, even basic visual dynamic to highlight, but the already-established precision of framing makes it clear that it is not one Stop Making Sense takes for granted, instead building up to and incorporating it as an anchor. And in this first instance, the shot doesn’t end there, either, with the camera moving back and to the right until Weymouth is back in view as well. It’s no surprise to see her there, but it is a pleasure to watch the film take note of its own updated and enriched spatial relationships in this way, and it’s felt time and time again.

Writing about this movie for the first time a little over a year ago after receiving it as a Movie Gift from ZoeZ (for which she has my eternal gratitude), I pinpointed the exact moment I realized I was falling in love with it: Byrne suddenly turning to face back-up vocalists Lynn Mabry and Edna Holt during an instrumental jam in “Slippery People,” to which they react by exaggeratedly playing air guitar and generally mirroring his movements. The band members had, of course, acknowledged each other’s presence before, but this is the first major instance when the contrast between them gives way to such direct interaction, and it’s delightful both because it’s so unexpected in terms of when-and-how and because it’s so obviously right and natural in the larger scheme: we had been approaching this development all along, even if we weren’t anticipating it.

There are additional, more specific reasons why this moment is so effective: the contrast (again) between Byrne’s eccentric vibe (although he’s plenty cheerful by this point) and Mabry and Holt’s more direct, unreserved joy (the latter, in particular, is visibly convulsed with laughter), the fact that both young women have been on the stage for all of three minutes by this point yet this little dance-off with the frontman implies complete mutual ease and familiarity, which in turn reinforces the inviting quality of the proceedings even for those who may have had little to no familiarity with Talking Heads going in. It’s an even more affecting recurrence of what Mike D’Angelo talks about in his Scenic Route on the opening number, when he describes being moved by Weymouth’s “unannounced,” already-in-progress appearance: “It suggests family rather than bandmates.”

This is a movie that works in an exceptionally elemental way: variously diverse subjects and objects fill out a particular space to perform a particular task, and the more of their collective energy gets channelled into it, the richer the result on both the micro and the macro level. Part of the genius of both the show and the movie lies in applying this organizational structure to a live rock performance whose own sole purpose is to be as thrilling as it can. The decision to eschew everything but the songs—which flows out of the way the concert itself keeps the focus squarely on the band, avoiding any stunts or pyrotechnics—is a prime example of attaining freedom through discipline: there’s no chance of things getting carried away; the people onstage get to be defined exclusively by what they bring to the table here and now, and the film is as rewarding as its attention to them, which dictates both its constantly shifting mise-en-scène and editing. Everything here is so unified that just about every shot organically sets up and/or pays off another one, whether they’re separated by a cut or by an hour. And because the filmmakers had the opportunity to capture the show over four nights and closely collaborated with the band from the start, they end up with enough precise footage to maximize the emotional impact of as many individual moments as possible while keeping them parts of a cohesive whole.

In its own way, the film finds a middle ground between filmed recording and drama; it adheres to the classical unities without being beholden to demands of character and narrative. Virtually every number gets treated as its own set-piece; with the stage and the band acting as constants, they can all be distinctive without ever feeling disjointed. Watching Stop Making Sense, I’m reminded not so much of most concert movies as of Bob Fosse’s Cabaret, which redefined the movie musical by “choreographing” its stage-set musical numbers not just physically but in terms of presentation, via razor-sharp shooting and cutting. Both films operate in this manner to provide their audience with the proverbial best seat in the house.

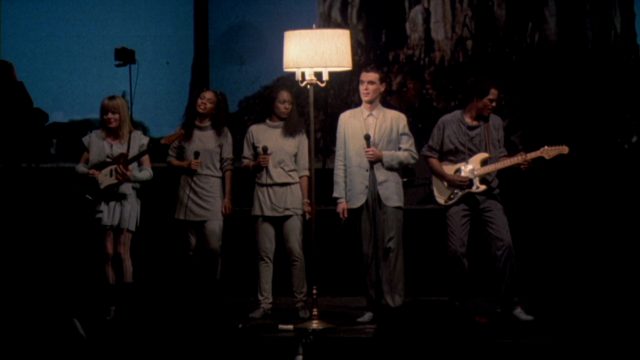

All throughout, the filmmaking continues to take its cues from the performances, with results that range from the crowd-pleasing bombast of “Burning Down The House,” the first number to showcase the entire nine-person lineup (the two early cuts to a wide shot that includes all of them, each doing his or her own thing, working in perfect harmony, are as thrilling as any action movie), and the unparalleled intensity of “What A Day That Was” to the cleansing communal spirit of “This Must Be The Place” and the locked-down view of a “Once In A Lifetime” that Byrne performs like a blissed-out preacher, the camera holding, holding, holding on to him until the cut to a wider view of the stage—and what a view that is—arrives with an explosive force. That “Day” and “Place,” which couldn’t be more different in tone, are placed next to each other right in the middle of the show, and both find their own striking use for the visual idea of light standing out against darkness, speaks as well as anything to Stop Making Sense’s way of mining its contents for all sorts of deeply satisfying juxtapositions.

When the performance, and the presentation, doesn’t have to be so rigorous, the camera is free to capture more interactions: Holt, Mabry, and the show’s percussionist and chief ham Steve Scales goofing off in the background, Byrne extending his mic to a lighting guy so the latter can sing the titular lyric, Weymouth crouching a little bit in anticipation then nodding to herself, satisfied, as she watches Byrne carry a song through a particular vocal repetition. Because these people never reveal anything of themselves outside of their performing, and are professionals at work first and foremost, every single little laugh, quick glance and appreciative nod registers as something special, a gift to the viewer. And it takes a movie that’s similarly appreciative of its subjects to avoid letting it interfere with its own job, yet still make sure to, e.g., cut to a close-up of Frantz at the precise moment Weymouth’s jailed heroine of “Genius of Love” is singing of “my boyfriend, my loving boyfriend.”

Some great movies are marked by a sense of looseness and spontaneity, others behave like carefully worked-out mechanisms; but more than perhaps any film I’ve seen up to this point, Stop Making Sense gives me the impression of a flawless living organism that naturally evolves with every second of its runtime. It builds and builds all the way to its final two epics, both as capable of being exhilarating in entirely offhand ways as anything in the earlier part of the movie; one of my favorite moments in “Take Me to the River” comes when the previously described Byrne-Frantz two-shot gets abruptly invaded by Scales sprinting merrily across the frame, which is topped off with a cut to Mabry laughing in their direction before turning back to her mic—a case of setup and payoff that was most likely never even intended as one, at least during filming, yet works gloriously. As the closer “Crosseyed and Painless” burns through at least four different stages while the camera hurtles around the stage, soaking in as much remaining energy as it can, and then finally goes—yes!—into the audience, Stop Making Sense comes right up to the edge of exhaustion; the only thing left for it to do is end. The musicians leave. The curtain goes down. The stage is empty again. What remains is the knowledge that people can do this—all of this—for one another.