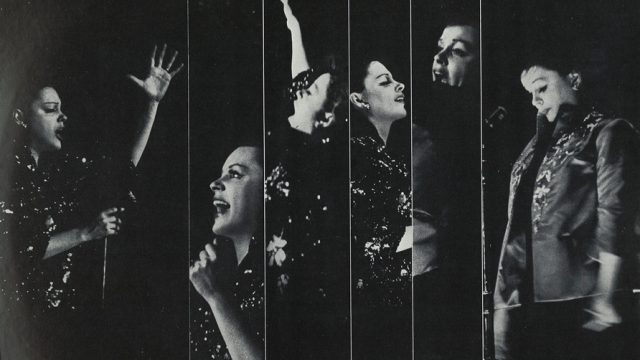

They called it “the greatest night in show business history”, because of course they did—it was the night Judy Garland solidified the most triumphant comeback in a career that called for a number of them, and it’s hard to talk about Judy Garland without hyperbole; both the personal and the professional highs and lows of her life usually merit if not openly court it, to the point where you may start to wonder where the hyperbole in fact begins. Judy at Carnegie Hall, both the evening and the record of it, would have no problem acquiring great acclaim and a legendary reputation (its energy memorably compared by more than one contemporary reviewer to that of a revival meeting), and one of the things that make it special as a live album is that it doesn’t take long to start hearing the seeds of that reception. The overture, comprising “The Trolley Song,” “Over the Rainbow,” and “The Man That Got Away,” by itself gets an ovation lasting a full minute, but then Garland actually sings her opening two numbers—“When You’re Smiling” and a medley of “It’s Almost Like Being In Love” and “This Can’t Be Love”—and what you hear is no longer just applause. It’s the sound of people getting their first inkling—or confirmation—that they may be about to witness something extraordinary, something beyond even what they’d hoped for.

Over the course of two hours, Garland performs 28 songs, the most important characteristic of which as a collection is that only two of them had been written within a decade of the concert, and all but six, in fact, predate the 1940s. These are all Great American Songbook standards, and it would be fair to call Judy at Carnegie Hall a nostalgic work, just as the act of listening to it today is nostalgic—but it goes deeper than a safe exercise in playing the hits, because these particular renditions gain power and resonance directly from who Garland was by this moment in time, all the history she had accumulated. These songs—most of them dating from the years when she was growing up, several originated or covered by her in movies—don’t give the sense that they ever really aged; she, however, did, and in Carnegie Hall they go beyond well-trodden professional territory. They represent something like a personal musical home, a sanctuary reached and taken comfort in once again, and to listen to them is to be invited inside.

Garland’s set list is both consistent and versatile, alternating boisterous up-tempo numbers—everything from “Puttin’ On The Ritz” to The Band Wagon’s “That’s Entertainment!”—with slower torch songs and plaintive ballads (“Stormy Weather,” “How Long Has This Been Going On,” “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”), sung softly into a reverent silence; in between, there’s space for a thunderous rendition of “Come Rain or Come Shine” that has to be heard to be believed, stories of wacky Parisian hairdressers and treacherous English journalists (but self-deprecating first and foremost), and an introduction to “San Francisco”, making fun of Jeannette McDonald’s warbling, where the mere mention of the singer’s name provokes immediate guffaws in the audience. Garland’s delivery, together with Mort Lindsey’s orchestra, can conjure up any kind of atmosphere—from a music hall to a smoky jazz club—in a matter of seconds; and in her vocals, one can hear all the personas she’d lived over the years—the vulnerable little girl, the game professional, the world-weary, sardonic chanteuse who’s seen it all.

Supported at all times by the orchestra, her voice dips and soars freely, often in a way that’s rewardingly counterintuitive: the likes of “Do It Again,” “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” and, in part, even “Stormy Weather” are borderline spoken-word, while the more lighthearted numbers often assume a surprising, stop-you-in-your-tracks intensity. It is a trademark quality of Garland that she took completely seriously even the things she didn’t (“By temperament she is incapable of holding anything of herself in reserve,” Shana Alexander put it in a contemporary LIFE Magazine profile that detailed Garland’s road to Carnegie Hall, which included a months-long bout of hepatitis, a subsequent “You can never work again” instruction and a brief period of retirement). And so, e.g. when she declares, at the top of her lungs, that “when you’re smiling, the whole world… smiles with you,” it’s not that she’s kidding herself or anybody else about the words being true: it’s that, for at least as long as the song is playing, we might as well believe them, or at least desire them to be true—a sophisticated sort of escapism, weightless lyrics invested with a real sense of longing that comes naturally to this particular performer, until it ends and she promptly moves on. In a way, it’s an extension/inversion of the dynamic demonstrated previously by Garland in A Star Is Born—most clearly, in “The Man That Got Away”, where the intensity of her simultaneously knowing and sincere performance rose up like a tsunami only to swiftly come crashing down into a wink and a smile, her Esther Blodgett joking around with the awestruck James Mason not half a minute later.

There’s an argument to be made for Garland’s as the ultimate show business story of the 20th century. Few, if anyone, both achieved and sacrificed as much as she did and remained so committed to sharing their gift with their audience over a career that was literally just a couple of years shorter than their life. When you get to that level, the poignancy of your work becomes self-generating, especially when said work has one foot in the past and the other in the present, a revisit of material already connected to someone you once were.

Which is to say that, for all its virtues as a self-contained record, the experience and the ultimate effect of Judy at Carnegie Hall is inextricably tied to how it, in the very fact and process of its creation, feeds into and out of the Garland legend and each individual listener’s level of familiarity with same, occasionally in ways not at all forced or even, perhaps, consciously realized by the woman herself. Take “Zing! Went The Strings Of My Heart”: on its own, it may be the most purely pleasurable rendition on the entire album, flawlessly arranged and bristling with joy and confidence (it probably didn’t hurt that it arrived two thirds of the way into the performance, when all involved already knew the night was a success but didn’t yet have to think about all good things coming to an end)—yet it plays a little differently simply when you know that the 16-year-old Garland had first rehearsed and performed this song the same day she learned her father was on his deathbed many miles away, and that the radio broadcast of it that night was the last time he ever heard her voice.

And then, of course, there is “Over the Rainbow”, which it would be impossible to perform without self-consciousness—and Garland doesn’t try to, simply committing to the lyrics from the point of view she’s now reached, her occasionally quivering voice (which may be genuine or a conscious decision, not that it really matters) neither denying the song’s place in her life nor forcing any associations, which take care of themselves. Here it is again, that ultimate anthem of yearning, now sung from, effectively, the other side of a hard, messy, profoundly exhausting life (even though Garland was not yet even 40), where any kind of long-lasting peace and contentment turned out to not be in the cards—and so “Why, then… oh, why… ca-a-a-an’t I?…” briefly assumes a ferociously disbelieving, one-last-cry-into-the-void quality, before it subsides into an acceptance and is left behind once more.

Even before “Over the Rainbow”—immediately preceding it, in fact—there is another moment the entire show had, in its way, been building towards. It’s late enough in the evening for people to start shouting requests, and, standing in front of a sea of voices, Garland can only respond, “I know. I’ll… I’ll sing ’em all, and we’ll stay all night!”—another thing that everyone in the room, judging by their reaction, doubtless wishes were true. That it can still make one wish that 60 years later speaks as well as anything to the hold Garland continues to have on her audience, and to the particular way she had of simultaneously filling a room of thousands of people with her voice and making you feel like she was singing just for you alone. Judy at Carnegie Hall was a triumphant comeback, but, like the others, it didn’t last for very long; Garland’s health would soon catch up with her again, and by the end of the decade, she was dead. But then all one has to do is cue up these songs, hear “Do It Again” practically whispered in your ear or the closing “Chicago” imbued with a sense of mischievous happiness—and there she is again, so far away and yet so close.