“Well then, this is a very important week for you.”

“This is the Funvee. The Humdrumvee is over there.”

Iron Man is the only movie in the MCU that doesn’t feel to me like a commercial for the next MCU film – it feels like a promise. Gillianren observed in her article how strange it was that Marvel kicked their cinematic universe off with a character even comic book fans weren’t champing at the bit for, let alone your average filmgoer (which in this case, I fit into – I’d never even heard of Iron Man), but rewatching it made it clear it was actually a pretty shrewd move. Structurally, Iron Man is an Origin Story charting Tony’s growth into superhero, a concept that’s pretty familiar to audiences, but combining it with the iconography of Iron Man creates a unique, specific emotional journey; even the other genius billionaire playboy philanthropist superhero of 2008 is nothing like Tony.

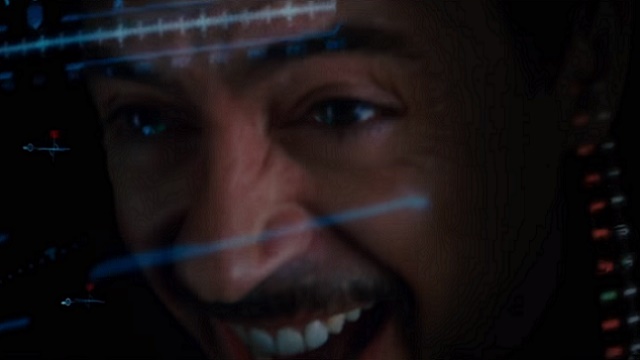

There’s a lot tying Tony into 2008, such as the generic Middle Eastern bad guys who speak every language aside from English, but the most significant to me is that Tony is the last gasp of the Asshole Who Gets Away With It Because He’s So Good archetype before it fell out of popularity, and I would argue it’s at least one of the more plausible ones – for one thing, Tony pays everyone tolerating him instead of the other way around, but also Tony legitimately is that charming. Everyone and their mums has said how apropos it is to cast an actor known for his skills and charm as well as his alcoholism and unstable behaviour as Tony Stark, and it really is one of the all-time ‘invent nothing, deny nothing’ performances – the things Robert Downey Jr does as an actor, improvising and experimentally throwing out remarks to provoke his fellow cast members, are in micro what Tony does in the story, taking the suit out and flying it as high as possible before it’s even close to ready, just to see what happens. If Peter Parker’s origin story is of a child forming a personal set of ideals, Tony Stark’s origin story is of a rock star scientist working out the most effective superheroism method.

Jon Favreau takes the canny route of having his choices as director reflect Downey’s as an actor; he leans in on both Downey’s personal skills and the behind-the-scenes chaos and allows an improv-heavy tone. The flipside of this being the MCU’s first jump in the pool is that their playbook hasn’t been written yet (that’s a working sport metaphor, right?), and overlaying an improv-heavy tone over a fairly generic late 00’s blockbuster structure and visual sensibility creates the sense we’re seeing the world through Tony’s eyes, and what he sees is a playground for him to experiment in. Practically speaking, no character in the movie is as interesting or as fun as Tony, but let’s face it, that’s pretty much how Tony sees the world. What’s more important is that they’re all given dramatic motivations that let the actors breathe a little life in them and create the sense that there’s a world outside Tony, even if he doesn’t much care – the most moving moment in the film is when Yinsen reveals he never intended to survive Tony’s escape (“My family’s dead. I’m going to see them now, Stark.”). The world might be Tony’s playground, but he doesn’t have complete control over it, and Downey even imbues Tony with a clear knowledge of that even before Yinsen’s sacrifice pushes him to heroism.

The weak point of the movie is the same thing that’s always been the weak point of Marvel movies outside representation: the villain. The third act hinges on the reveal that Obidiah Stane, Tony’s business partner and vague father figure, is selling weapons to terrorists under Tony’s nose and has resented working under a privileged manchild for so long. As much as Jeff Bridges acts the shit out of it – I love how still his posture becomes post-reveal, something genuinely larger than life – it’s not that particularly shocking or upsetting a twist. I find myself thinking of one of the all-time great twist movies, Fight Club. Take out the twist, and the Narrator and Tyler’s story is still one of a charismatic anarchist pulling a weaker man into his orbit as they create a strange and loving partnership, one with peaks and valleys and dramatic choices; more importantly, the Tyler Durden before the twist and the Tyler Durden after are clearly the same person with the same personality and motivation, it’s just the context is different. Even if Stane and Tony’s relationship had been a complex back-and-forth of choices (which it isn’t), Stane’s personality completely flips, and what follows isn’t a sadly logical sequence of events that could have been avoided if only we knew then what we do now, but arbitrary CGI with an admittedly clever conclusion.

To a large extent, this is something casual filmgoers don’t notice or care about – there’s no way the MCU could make enough money to cancel out the debt of a small country if they did – and I know when I saw it in cinemas, I knew enough about movie trilogies to know once the groundwork is laid, the second movie can improve on the first (see Spider-Man 2). Where the top rights itself again is in literally the final moment of the film, when Tony impulsively reveals to the world that he is Iron Man. It’s one of those genre subversions that lasts beyond the initial thrill; it was certainly fistpumping to see a movie superhero flip the bird to the secret identity in 2008, but it managed to pull off the neat trick of not just establishing the MCU – this will be a world where not only does a superhero like Iron Man exist, everyone knows he’s Tony Stark – but of concluding the story it was telling. If this is the story of Tony Stark taking up the mantle of Iron Man, him literally declaring so doesn’t just provide closure, it does so in a way that’s true to the character and tells us exactly what kind of hero he’ll be: one who, against all advice, seeks out the highest risks for the highest rewards. At first, that looked to be the mission statement of the MCU.