I recently called Tim Burton “baby’s first auteur,” but that’s not exactly true. I really learned the importance of the director from Looney Tunes. Watching the classic cartoons and learning about them from the documentaries included on the tapes and discs, fansites, and books like Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice and Magic, I learned the personalities behind the camera were every bit as interesting as the ones in front of it. There was Tex Avery, who practically invented the concept of cartoon physics; Bob Clampett, whose animation passed fluidity and went straight into liquidity; Bob McKimson, who invested his characters with wide-mouthed, gesticulating energy; and Frank Tashlin, who brought cinematic language to his cartoons the same way he brought cartoon techniques to his live action films with Jerry Lewis and Jayne Mansfield. The king of them all was Chuck Jones, mixing his distinctive design sense and the witty wordplay of Michael Maltese’s scripts with his equal skills with the comedy of broad facial expressions and subtle gestures. But there was also the more unassuming but even more impeccable craftsmanship of Friz Freleng. And in the forties, while Chuck was still finding his voice, Friz was the greatest director on the lot.

Freleng wasn’t quite a true auteur. He was only as good as the studio around him, producing classics at its height and mediocrities at its nadir. But he was certainly the most faithful to Warners through all these up and downs, from its prehistory working under Walt Disney on the silent Oswald shorts through its post-history as the cofounder of DePatie-Freleng studios. He created classic characters like Speedy Gonzales and Sylvester the Cat, and was the sole director of Tweety Bird and, most relevantly, Yosemite Sam.

As for auteur credentials, Freleng’s professionalism was so complete it became a trademark. No one in the animation world understood comic timing like him, and he got there not by innate genius but by painstaking work. He would work out his gags not just on storyboards but in sheet music, and High-Diving Hare, even more than his many works based on compositions by Liszt and Brahms, is something like a cartoon symphony.

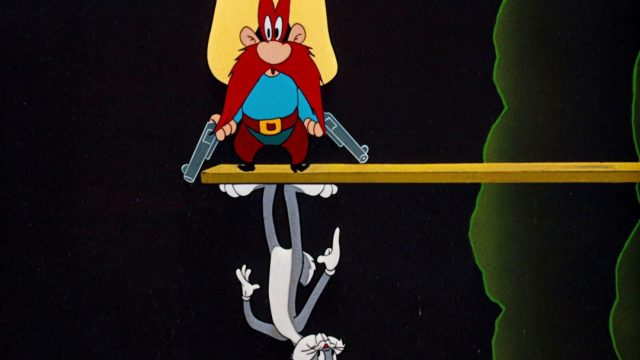

All that complexity requires an incredibly simple frame to work. In fact, Freleng called it “risky, because it was a one-gag cartoon.” Bugs Bunny plays the Master of Ceremonies for a vaudeville show, featuring the high-diver Fearless Freep. (As far as auteur trademarks, Freep’s name is a sneaky one as, even though the producers demanded he be given the more dignified credit of “I. Freleng,” Friz and his crew loved to sneak variations of his nickname into their shorts. See also a background sign advertising “Frizby the Magician.”) Yosemite Sam, fanatical Fearless Freep fanboy, is so excited to see his idol he empties his revolvers into the ceiling, and demands, “A whole mess a’ tickets! I’m a-splurgin’!” But just as Freep’s about to come onstage, Bugs receives a telegram saying he won’t be there. Furious Fearless Freep fanboy Yosemite Sam demands Bugs take his place on the diving board. He forces Bugs up the ladder at gunpoint, and Bugs tricks him into diving in his place. And then, like the man said, wash, rinse, and repeat.

The magic’s all in the timing. Friz has the patience to make High-Diving Hare a slow burn, spending two and a half minutes on setup, making sure to emphasize the staggering height of the diving platform, with just a few easygoing gags to lull the audience before it all explodes into chaos. The first dive takes nearly two minutes for Sam to demand Bugs take the plunge, the camera to show off the loooong walk up the ladder, Bugs to change into a comically old-fashioned bathing suit, flip the board backwards, and convince Sam he dived with the help of a glass of water he pulls from somewhere just offscreen, before Sam finally falls off the edge.

From there, the cartoon tapers into an increasingly frantic pace. The next two gags are half a minute each; the fourth is twenty seconds; the fifth and sixth are only fifteen seconds each. The second time, Sam has to make another speech before marching Bugs up the ladder; the third, he only gets a far as “Up you go,” and our hero just shrugs and goes along.

This sets up one of the best and simplest gags in the entire Looney canon: after six run-throughs of “climb, trick, fall, splash,” Freleng trusts us to fill in the rest ourselves. Sam continuously runs up the ladder and immediately falls down again, with no indication of how Bugs tricked him into diving. The comic repetition crosses the line into hilarity with some help from composer Carl Stalling, who reuses the same tune in time with Sam’s footsteps every time he climbs up, and the same slide whistle every time he falls down. And then, when the music stops, we know something’s up.

That’s not the only time Freleng gets a big laugh out patiently setting up and then upending our expectations. After knocking Sam off the platform the second time, Bugs remembers, “Uh oh! Forgot ta fill da pail with watah,” and dumps a bucket down after him. Sam frantically prays the water gets ahead of him, and, thanks to the miracle of cartoon physics, stomps on it to make sure it does. After several seconds, he finally succeeds, and the water safely lands in the pail…only for Sam to loudly crash through the stage a foot or more away.

But what happens when the music stops at the end? Well, after a second or two of dead silence, we hear Sam sawing away, and the next shot reveals he’s hogtied Bugs into an elaborate trap to keep him from getting away and is cutting the board loose from the platform. Escape is clearly impossible, so we have a pretty good idea of what to expect, until…he finishes cutting through the diving board and the rest of the platform collapses to the ground with a wonderfully overkill clattering from sound effects maestro Treg Brown, while the diving board remains inexplicably floating in midair.

I firmly believe Bugs Bunny is one of the greatest characters in modern fiction, and this gag goes a long way to showing why. Chuck Jones, in his memoir, Chuck Amuck, describes the wealth of comedy Warners’ got from its stable of eternal losers, and how Bugs is unique as what he calls a “comic hero.” More than James Bond, more than Batman, Bugs is the character we all wish we were, doing everything we always wanted to without facing any of the consequences, triumphing with minimal effort over impossible odds. The cosmology of the cartoon universe bends over backwards in Bugs’ favor just like it does against Daffy Duck or Wile E. Coyote, and his closing line in High-Diving Hare might be the best summation of the potency of that fantasy.

“Ehhh…I know dis goes against da law of gravity, but uh…ya see, I never studied law!”