You’ll get no argument saying Nina Simone’s a great artist. But like so many of the greats, it’s much harder to nail down just what kind of artist she is. Both jazz and soul fans have tried to claim her, but either one of those genres accounts for only a fraction of her work. It might be more accurate to say she’s the last of the great all-around entertainers — the heir to Harry Belafonte and Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, the kind of lounge singers who could play anything the audience requests and play the shit out of it. One of Simone’s most shattering songs is a fucking show tune for fuck’s sake.

That’s a type of artistry that doesn’t get the recognition it deserves any more. As Simone rose to fame in the late ’50s and early ’60s, so did the new breed of singer-songwriters, who’d warp the entire field of music criticism around them. The criteria for popular music became personal expression above all else. “They don’t even write their own songs” was treated as a coherent criticism.

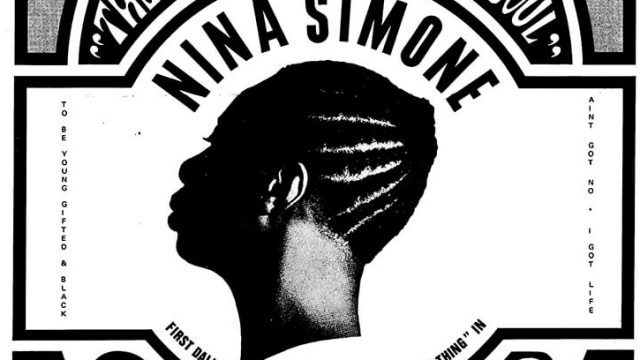

But interpreting songs is just as valuable. Versatility is an underappreciated skill, and putting on another writer’s costume while still remaining yourself is one only an elite few can claim. Nina Simone was no slouch on the songwriting front — “Four Women,” “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” “Mississippi Goddam.” But she dipped her toe in that pool relatively rarely, and you’d never know it. Every song Nina Simone sang became a Nina Simone song.

And if no one will argue about Nina’s talents, she, like all the great interpretive singers, is rarely recognized for her consistency. Acclaimed Music’s survey of thousands of critics’ lists turned up plenty of Simone’s individual tracks but few of her albums. Here Comes the Sun is nowhere to be found. One of the few reviews I was able to track down online, from Allmusic, is lukewarm at best. We already saw with their take on R.L. Burnside’s I Wish I Was in Heaven Sitting Down that the site’s critics are too quick to dismiss an artist stretching out of their comfort zone as a has-been trying to keep up with a world that’s passed them by. That same bias accounts for their review of Here Comes the Sun, which they place “just past the point where a great artist reaches too far for new material.”

Well, what do critics know anyway? (Present company excepted, of course.) Even in 1971, a decade and a half into her career, Nina Simone was kicking the asses of everyone in the pop music world, some of whom she covers on Here Comes the Sun. Nearly all the tracks on this album were hits for other artists. And nearly none of them were ever half as good as they are after Simone got done with them.

She lays down the gauntlet with the opening, titular track, taken from the catalog of the Certified Greatest Rock Band Who Ever Lived. Simone blows them clean out of the water. The original “Here Comes the Sun” is a stoned, lazy, good-vibes kind of a song. “It’s alright,” George Harrison sings, but he doesn’t make it sound too much better than that. Simone takes it a couple hundred miles further. Her jazz training kicks in, and she hits strange notes few pop artists could even find on the scale, bouncing around in patterns well divorced from the usual pop melodies. She warps the Beatles’ descending phrase, ending on a high note she seems to reach for as if she was reaching for the sun itself. By the last chorus, she hits the edge of her range and holds it for a mood of transcendent yearning that gives me chills. When she says, “It’s alright,” it’s not a good vibe, it’s a hard-won victory. You really believe “It’s been years since it’s been here.”

By 1971, Simone’s labor in the fields of civil rights activism had taken its toll. She fled to Barbados the year before, and her personal crisis might account for the absence of explicit political material here. But that would be too simple. Simone makes every song on Here Comes the Sun a song about the struggle, whether that’s what it was originally about or not. There’s nothing abstract in her interpretation of the Beatles’ metaphor. The sun is the “new day” Simone returns to later in the album, the dawn of freedom for Black America.

No song on Here Comes the Sun changes more in Simone’s hands than “Just Like a Woman.” Bob Dylan’s song is one of the saddest things he ever wrote, but it took other artists to prove it. He delivers it on “Blonde on Blonde” with a sneer and so much irony he could be doing an impression of himself. It’s another in the long tradition of Dylan kiss-offs along with “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Positively 4th Street,” with only occasional glimmers of the sadness that deepens entries like “It Ain’t Me, Babe” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

But what isn’t in Dylan’s performance is still hiding in the lyrics, waiting to be discovered. Simone wasn’t the first to discover it. Roberta Flack had gotten to it a year earlier on Chapter Two, flipping the perspective to empathize with this poor woman — not “She aches,” but “I ache.” Simone does something similar, but she lets it sneak up on you. She sings the first six verses with more tenderness than Dylan, but still from the safe distance of the third person. And then for the kicker, she turns the song on its head. Dylan had already built that last two verses up for Simone’s payoff, dropping the third-person mask and admitting to some real pain:

Your long time’s curse hurts,

And what’s worse

Is this pain in here.

I can’t stay in here.

Even if he drops back into his snide persona to dick around with the melody of “Ain’t it clee-uhr?” Simone has no time for games. She draws the notes out in that phrase and repeats it as the music swells around her. She slows down and quiets down to say, “Please don’t let on/That you knew me when/I was hungry/And it was your world,” turning the line into a confession. And then the kicker:

I take

Just like a woman

Yes I do

And I make love

Just like a woman

And I ache

Just like a woman

But I break

Just like

A little girl.

And with that small change, the whole song opens up. “Just Like a Woman” isn’t about self-righteous condescension. It’s about a woman who can diagnose her lover’s faults with painful accuracy because she sees them in herself. Dylan was obviously paying attention, because he’d use the same trick in “Idiot Wind” four years later. And so was the rest of the music world. The tragedy Simone unearthed in “Just Like a Woman” became the default interpretation, even when it ended up back in the hands of a male artist like that latte-day all-around entertainer Jeff Buckley. Nearly half a century later, Charlotte Gainsbourg would bring it to its final fulfillment for the I’m Not There soundtrack. She slows the tune down to a crawl and sings it in a whisper — the oldest trick in the book for hack singers trying to sad up a song, but against all odds, she makes it work.

Here Comes the Sun keeps up a steady level of greatness but there’s only one time it hits the heights of that opening one-two punch. Next to those two pillars of Boomer rock, Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mr. Bojangles” is a relative deep cut. Simone turns it into the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard.

She shows her mastery of the high note again, investing it with a lifetime’s worth of yearning, turning it into something transcendent. She does it again on “How Long Must I Wander,” inserting a wordless, soprano-high note into the middle of the title phrase. She doesn’t go for those kinds of pyrotechnics on “Mr. Bojangles.” It’s an intimate arrangement with a small band you could imagine gathered around the hearth. And when she stretches out that high note on Bojangles’ name, the music drops out completely except for some brushing on the drums, letting you focus on nothing but that beautiful, beautiful voice.

“Mama” Cass Elliot’s “New World Coming” and the Five Stairsteps’ “Ooh Child” both had revolutionary undertones already with their promises of better times. But leave it to Nina Simone to make it more than just words. She completely reshapes “New World,” taking us to church with a goosebump-raising reading from the Book of Revelation as the instrumentals and backing vocals crescendo into a frenzy. They’re words of comfort, but also of terror — before we can get to the crowning of the souls who triumphed over the Beast, Simone sinks her teeth into the warning of “the seven last plagues, for in them is filled up the wrath of God.” I’m reminded of the righteous fury of Simone’s Pirate Jenny burning the city to the ground, or the Sinnerman who finds the sea burning, and before that, of the traditional spirituals that veiled dreams of justice against the slavers in the prophecy of the last days.

These songs are about the fulfillment of the promise. But in 1971, it hadn’t been fulfilled, and in 2021, it still hasn’t. Simone grapples with those emotions on “How Long Must I Wander.” As the backup choir repeats “How long, how long?” I’m reminded of another biblical passage, the Psalmist’s anguished, “How long, O Lord?” When she asks, “How long must I wander?” one last time, she lets the music drop out except for one bare piano and leave her voice alone. She puts the classical beauty of most of her vocals to one side, shouting out until her voice cracks.

The original release pulls back from that despair to end on a note of triumph. “My Way” is the kind of smug, cheesy kitsch that gave the previous generation of all-around entertainers a bad name. But Simone never saw a song she couldn’t make work. “My Way” is the anthem of men who were born on third and thought they scored a triple. It means more when Nina sings it just on the basis of Nina singing it. Her race and gender mean the deck was stacked against her, and if she could claw her way to the top despite that, she has every right to brag. The record shows she really did take the blows, a much more powerful image than the original’s “took the pose.” And with her co-arranger Harold Wheeler, she takes “My Way” a million miles from its usual lazy lounge energy, pumping it up with furiously banging bongos to match the grandiosity of the lyrics.

The streaming version of Here Comes the Sun includes six more tracks that I’ve been frustratingly unable to find the provenance of. Her cover of Judy Collins’ “My Father” is a wonderful glimpse into Simone’s creative process. You can just hear her saying “That trips me,” under the piano before she begins, but she does her best with it for a minute or so anyway. After singing, “My father always promised me/That we would live in France,” she mutters, “You know you don’t believe that.” She makes it almost to the end of the first verse before she cuts the take short. “My father always promised me that we would be free,” she says, “but he did not promise me that we would live in France.”

It’s a stark reminder of the gulf between Black and white America’s dreams. And it’s proof that singing other people’s words didn’t doesn’t make Simone’s music any less personal. If she couldn’t make it personal, the song didn’t make it to record. (She’d finally finish recording it in 1978 for Baltimore.)

At least one bonus track can stand alongside anything that made it onto the first pressing. Most of the album looks forward to the future with hope, and if there’s elements of despair in “How Long Must I Wander?” they don’t win out entirely. “22nd Century”’s future is downright apocalyptic, and not in the triumphant sense of “New Day Coming” either. It begins, “There is no oxygen in the air” and just goes downhill from there. And it’s not far off either. The refrain insistently reminds us

Tomorrow will be the 22nd century

Tomorrow will be the 22nd century

Tomorrow will be the 22nd century

It will be

It will be

It will be.

Simone works herself up into a prophetic frenzy until words fail her and she starts scatting in tongues like a holy roller Ella Fitzgerald. And the arrangement more than keeps up with her. The music sets the mood with what seems to be the ghostly creaking of invisible fingers on the piano in a haunted house — actually a steel drum.

The streaming version of Here Comes the Sun ends with folksinger Melanie’s “What Have They Done to My Song, Ma?” It’s an ironic choice. What has Nina Simone done to these songs? Whatever she wants. And they’re all the better for it.