For all its flaws, Doom Patrol is an absolute masterpiece. Morrison was always one of comics’ most allusive writers, weaving his encyclopedic knowledge of myth, religion, and other comics into his stories. But next to Doom Patrol, even the reference pool of hisother work seems no deeper than tthe average stoned freshman’s. Its first story the previous year combined the turn-of-the-century German children’s book Struwwelpeter with Jorge Luis Borges’ magic-realist story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” And that was just a warm-up. The rest of Doom Patrol draws on a list of references that would make even Borges’ head spin, in everything from art history to alchemy to fairy tales to rock to psychoanalysis.

The Painting That Ate Paris updates the old sixties superhero formula of stories that doubled as science lessons as the heroes used their knowledge to piece together clues, turning the story into a whirlwind tour of turn-of-the-century art styles as the Doom Patrol is thrown through the painting’s different levels, from surrealism to symbolism to futurism to dada. Morrison’s obsessions with whatever odd and obscure subject he’s looked into often repeat throughout his work, and 1990 is a rare chance to watch that process in real time, as both Doom Patrol and Gothic turn the concept of cathedrals as amplifiers of psychic energy into major plot points. (You can see Gothic introducing another idea Morrison would return to when he took over the main Batman book over a decade later, pitting the Dark Knight against an immortal devil worshipper. Morrison would later make this character even deadlier under the name Simon Hurt, with the added wrinkle that he just might be Batman’s father and/or the devil himself.)

Unfortunately, Morrison would never weave together this many threads again. Blame Alan Moore. In Supergods, Morrison recalls how Moore had dismissed Morrison’s breakthrough the previous year with Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth as “a gilded turd” and “the 300-page equivalent of a 6th-form poem”: “The accusations of pretension stung horribly. I was a working-class dropout pretending to be the art student I never was…The obsession with art and fashion, myths, and popular music with which I’d separated myself from my roots now seemed as false as Granny’s teeth. No more ‘influences,’ I decide; no more plagiarism or quotes from the Romantics. I would shave my head before male pattern baldness could set in and be my own naked self.”

It’s a shame, because Doom Patrol is all the more profoundly original for its borrowings from the world of fine art. In Supergods, Morrison says, “I was using surrealist methods: automatic writing, found ideas, and even my word processor’s spell-check functions to create random word strings with syntax.” He goes on to describe how that created ominous but meaningless dialogue for his throngs of faceless horrors, but there seems to be a similar process at work for many of his plot points. Just look at the Cult of the Unwritten Book, whose members include such bizarre combinations of mismatched parts as the Starving Skins, Hoodman Blind and Hoodman Shame, who steal words off the tip of your tongue, and the Pale Police, assassins who spend a week meditating on their victims fingerprints in the hopes of trapping them eternally in the maze contained within them, have giant, lippy grins on their chests, wear Halloween masks on their belts, and talk in anagrams (including “This!”).

Sometimes all this creativity works against them — even the militantly normal Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E. are just as weird as everybody else. This may have been an attempt to showcase their hypocrisy, but it ends up making it look like Morrison and Case could only paint with one brush.

The Cult of the Unwritten Book storyline has its own flaws. After pages of restless invention — one of Morrison’s greatest gifts is an imagination that throws out ideas faster than you can read them, and one of his greatest tricks is to suggest dozens of them in quick succession so that they become more intriguing in their vagueness than the ones most authors build whole series on — the story shudders to an anticlimax. It’s a loose retread/parody of Moore’s Swamp Thing story “The End.” Like that story, it pits its heroes against God’s own shadow, here called the Decreator. Like Moore’s John Constantine, Morrison’s parody, the wonderfully useless drunk coward Willoughby Kipling, fails to prevent the horror from entering our world through sheer incompetence. But somehow, Morrison manages to come up with an ending even more horesshit than Absolute Good and Absolute Evil making nice because is Evil really all that bad, mannnn? Using the amplifying powers of Antonio Gaudí’s cathedral, the Sagrada Familia, Crazy Jane manages to slow down the Decreator. It’ll still de-create the universe, but so slowly we won’t even notice for years. And then, like Leonard Nimoy, the Doom Patrol declare their work is done here.

However revolutionary Morrison’s writing is, Doom Patrol is also revolutionary on a much deeper level. As we’ve said before, “queer” can also be a synonym for “weird,” and the subtext if this misfit band of outsiders is never far below the text. The heteronormative implications of the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E.’s mission to eliminate “quirks” is reflected in their choice of target: Danny the Street (punning on the celebrity crossdresser Danny LaRue), a living road they declare a “transvestite” because it decks out manly business like gun shops in frilly “clothes.”

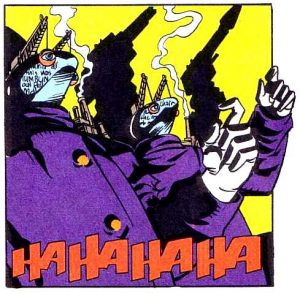

Danny later becomes a permanent member of the Patrol, and even before he met them, he was a haven for the people who had nowhere else to go, including Tom of Finland beefcake Flex Mentallo, the kind of found family that’s so important to queer culture. In the same way, the Brotherhood of Dada unites the outcasts who have rejected or been rejected by square society. They’re inspired by the original Doom Patrol’s Brotherhood of Evil, but they’re more antiheroes than evil themselves. They use the power of dada to save the world from another apocalyptic villain, the Fifth Horseman, and they’re rewarded with the chance to create a new life within the painting, a world without rules that they can make in their own image.

Morrison’s reinvention of the original Doom Patrol’s Negative Man is likewise just as queer as it is weird. Calling themselves by the alchemical term “Rebis,” they’re now a fusion of Larry Tranor, the original Negative Man, and his successor Dr. Eleanor Poole, existing outside normal ideas of race and gender as a fusion of male and female, black and white.

Morrison’s record here isn’t perfect. The Painting That Ate Paris’ climactic chapter reveals the Brotherhood’s token Black member is a stereotypical illiterate and making it deeply difficult to ignore that misstep through his misspelled narration. And Rebis’ teammate Robotman, the salt-of-the-eath heart of the series, continues to insist on calling them “Larry,” which in these more sensitive times seems an awful lot like the trauma of deadnaming.

But I don’t think it’s a stretch to say Morrison’s work here paved the way for his succession on the title by openly transgender novelist Rachel Pollack and her own introduction of Coagula, one of the earliest transgender superheroes, and one Pollack was free to write without comic book metaphors or sci-fi explanations. Pollack even slyly acknowledges that debt by making Rebis the source of Coagula’s powers.

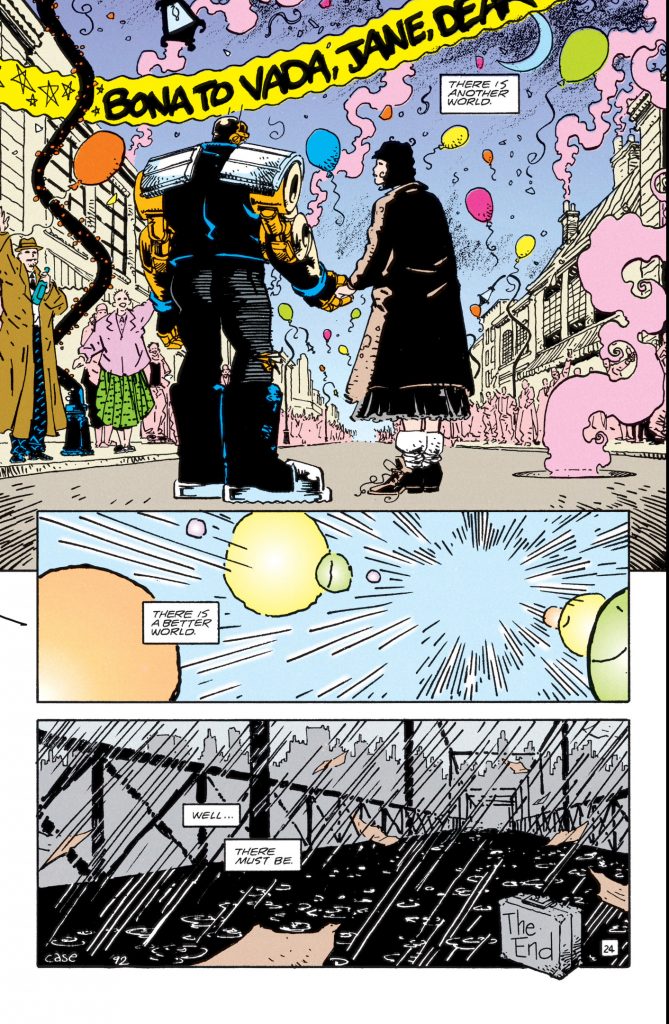

Grant Morrison has spent his career showing the comics world how futile it was to merely reflect reality when the medium was capable of so much more, but rarely as eloquently as the one-two punch of 1990’s Animal Man and Doom Patrol stories. It’s an idea he’d develop to its fullest when Doom Patrol ended a few years later. Danny the Street has expanded to Danny the World, and Robotman rescues Crazy Jane to take her there after she was exiled from the DC Universe to our own dreary reality.

Want to make a better world for Sam? Then donate to his Patreon!