When I was a kid, one of my favorite Looney Tunes cartoons was Duck Amuck (why? If I’m being honest, mostly because all the books said so). I watched it dozens of times, laughing at poor hapless Daffy Duck battling with his own animator. When I rewatched it in college, though, I realized it was something else. This wasn’t just cartoon comedy. It was pure existential horror, a little man at the mercy of a godlike creator who isn’t loving or fatherly or even indifferent, but openly hostile. How do you fight an omnipotent enemy?

I can’t be sure these same thoughts were on Grant Morrison’s mind when he was writing Animal Man — but I can speculate, especially since he was inspired to have his hero meet his creator after writing an earlier one-off story, “Coyote Gospel.” That story featured another Chuck Jones Looney Tunes creation, the thinly disguised Crafty Coyote, and ended with an enormous paintbrush reaching in from somewhere just out of frame, looking for all the world like Duck Amuck’s unseen animator.

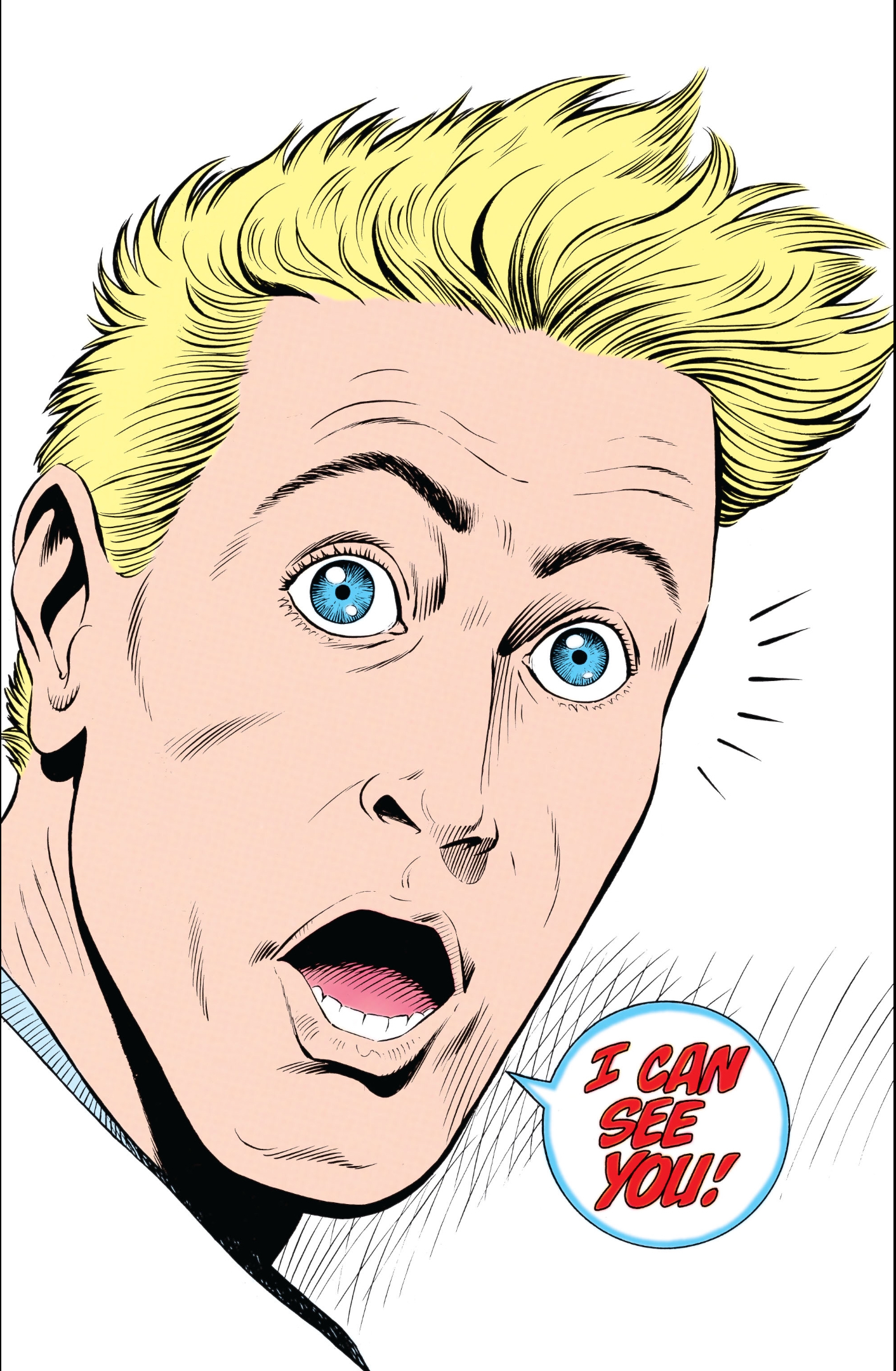

Whatever the inspiration, Animal Man takes this concept to even darker places. Self-aware comic characters were nothing new, of course. Deadpool was still a few years away, but Keith Giffen’s Ambush Bug and John Byrne’s She-Hulk were already chatting up their readers while Animal Man was on the stands. Even straightlaced old Superman habitually winked directly at the readers. They mostly took a Looney Tunes-style approach to the fourth wall, taking our existence in stride. Animal Man goes to much scarier places, something closer to the dark, existential postmodernism of theater like Six Characters in Search of an Author or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Morrison had been laying the groundwork to forcibly enter Animal Man’s world ever since “Coyote Gospel,” but he kicked off 1990 by yanking the rug out from his hero entirely. I first saw Animal Man’s moment of realization completely without context, in an online article much like this one, and it still scared the shit out of me.

This happens after a mysterious character, the Indian physicist James Highwater, appears, being literally deconstructed into a pencil sketch, in the home of Buddy Baker, the Animal Man. Highwater had followed a series of mysterious signs, apparently from Morrison himself, that further lead both of them on a vision quest in the deserts of Arizona (a ritual that, fittingly enough, involves meeting one’s spirit animal). That quest is already underway when 1990 begins, and when Buddy thinks he’s discovered the secrets of the universe, he finds the universe still has more secrets to reveal.

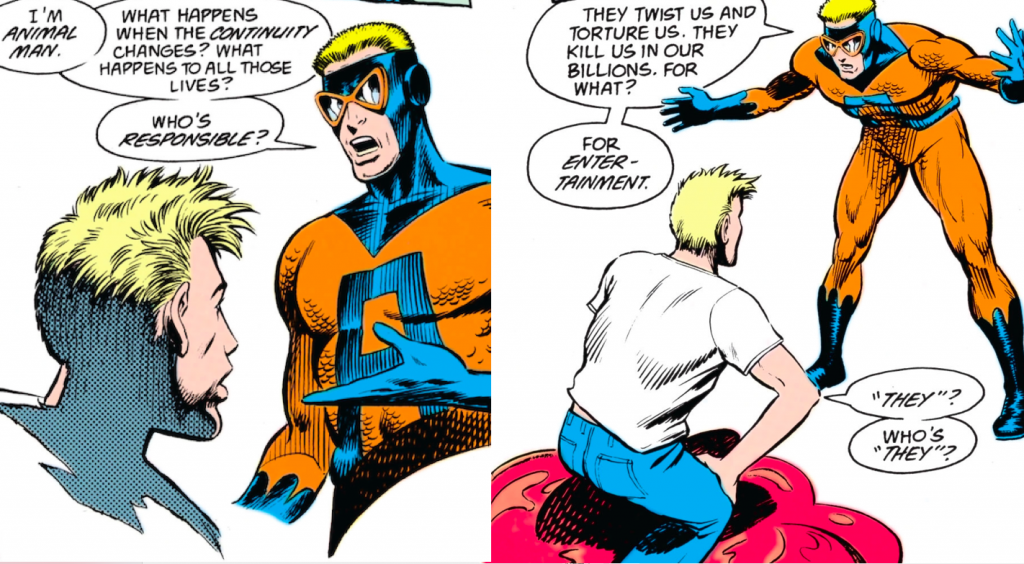

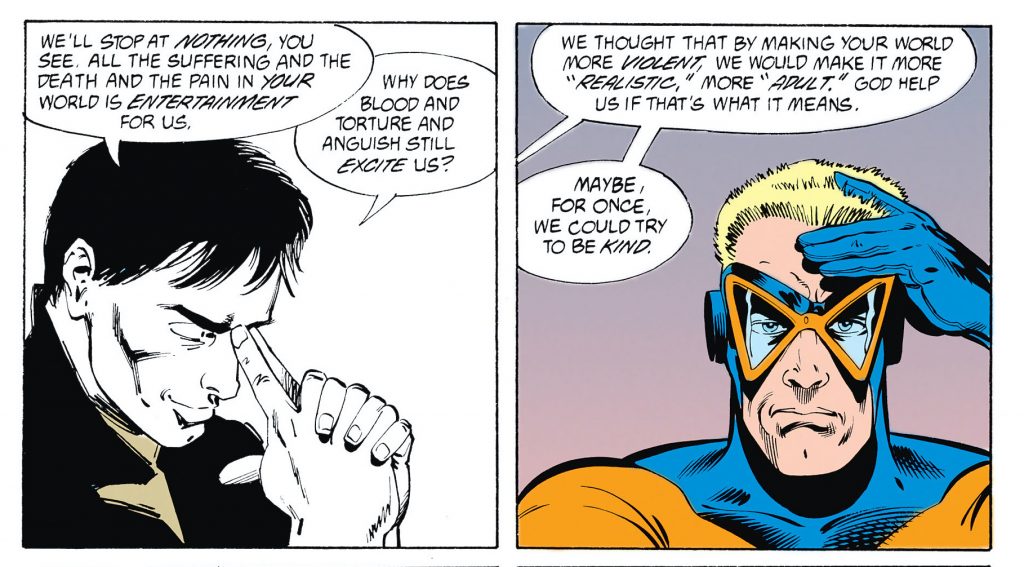

Under the influence of peyote, Buddy meets himself. Not in the usual sense of self-discovery — instead, he sees the ghost of another, dead self, who died when the 1985 miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths rewrote the history of the DC Universe. As we’ve seen, most comics use the fourth wall for brief gags, but Morrison examines the implications more deeply, and they’re very disturbing indeed:

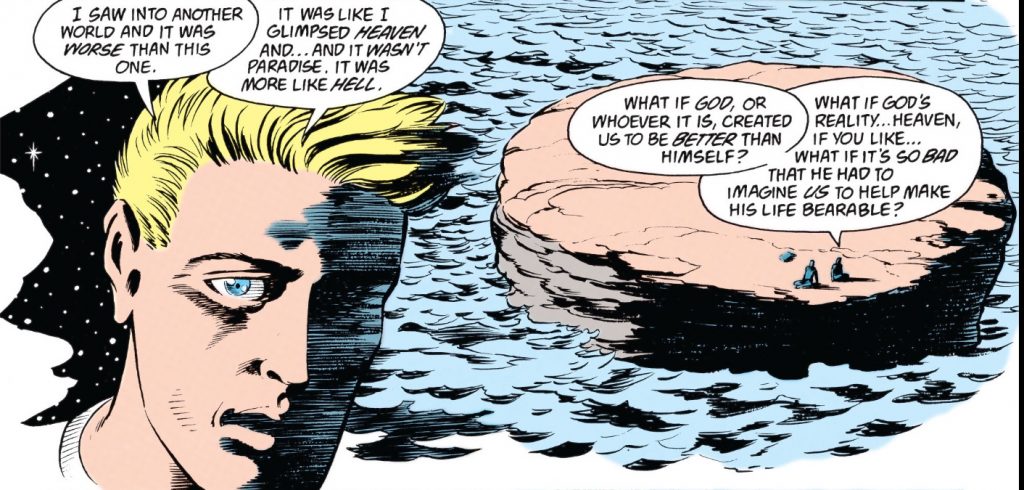

It only gets worse from there. Buddy comes home to find his wife and children have been murdered in retaliation for the ways he has disrupted big business in his crusade for animal rights. He eventually gets revenge, but before he can, Morrison devotes a whole issue to Buddy reacting to his overwhelming loss in more relatable, human ways. Brian Bolland’s cover shows him in an extremely unheroic pose, lying on the bathroom floor in fetal position, pills spilled around him.

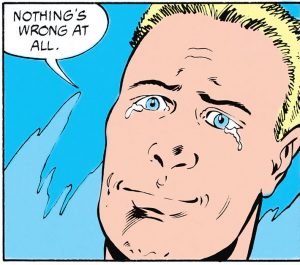

Comics at the time were all about heroes animated by tragedy, but Morrison knows that real tragedy doesn’t animate people. It immobilizes them. Traditional superheroes and action heroes promote ideas of stoicism is manly and emotion is a sign of weakness. Morrison shows weakness is human: Buddy is even seconds away from suicide before his old enemy Mirror Master reveals he can help him get revenge.

Buddy carries it out coldly and mechanically, before realizing that, again, the other comics lied. There’s no catharsis here. He tries and fails to prevent his family’s death with comic book science. Finally, he meets his creator. Their conversation seems to be futile until Buddy returns home to discover Morrison, as his last act before leaving the book to another writer, had given Buddy his family back. It’s one of the most cathartic moments in comics history, which is no small feat given what a cop-out the “it was all just a dream” resolution is, as acknowledged in the story itself, or how much it’s hampered by Chas Truog’s terrible, terrible art.

In 1990, comics were in a very dark place. Creators like Frank Miller and Alan Moore had taken the superhero genre to new, grim places, and dozens of other, lesser writers gracelessly imitated them, filling the racks with suffering and death. Morrison saw this as a cheat, imposing the values of reality on the comic book universe: “They bullied defenseless fantasy characters into leather trench coats and nervous breakdowns,” he says in his memoir-by-way-of-comic-book-history Supergods, “and left formerly carefree fictional communities in a state of crushing self-doubt and dereliction.”

Animal Man was his pushback against these trends. He didn’t see it as postmodern, but as taking his contemporaries’ pursuit of realism one step further. After all, the reality of these fantastical fictional characters is that they are fantastical fictional characters, and the stories would be more believable by embracing that fact rather than forcing them into roles they were never meant to play. The letters printed in its back pages indicate it worked. They’re full of readers whose reaction to the Baker family’s death isn’t shock or intrigue but horror and demands to bring them back whatever it takes. In his on-page appearance, Morrison dismisses this kind of story: “All stories need drama and it’s easy to get a cheap emotional shock by killing popular characters.”

The thing is, he’s too good of a writer for his own good — Animal Man’s death and grief isn’t cheap. It’s incredibly compelling, far more so than the comic-booky story of a Second Crisis caused by the return of all the characters killed in the first one that interrupts the main plot. At some level, Morrison seems to have understood this. It’s unlikely he would have devoted most of a year to a story that amounted to showing other writers what not to do. Even the macho revenge plot takes up a whole issue, and it’s a thrilling issue too. But then, as we’ve seen, the story takes its power from showing how real grief isn’t thrilling or macho at all.

The trouble is, that is what it means, and creating fictions where it isn’t doesn’t do anything to change it. Morrison’s right to a point, of course — most of the attempts to adult up superheroes were, in the supervillainous Psycho-Pirate’s words, “stupid.” And we do need the escape from that harsh reality that old-fashioned comics provide. But grim realism has its place too, and as his other comics from 1990 show, even Morrison himself wasn’t immune to its worst excesses. The real crime of injecting the horror of real life into comic-book fantasy isn’t how it corrupts the fantasy, but how it trivializes the reality. And yet, Morrison begins his Batman story, Gothic with a gangster threatening to force a man’s wife and children into a life of unwilling sex work and offhandedly alludes to mass rape in the backstory of its villain, Mr. Whisper.

And in Doom Patrol, Morrison commits one of the worst sins of grim-ification by injecting rape into the backstory of his heroine Crazy Jane, who has a different superpower for each of her multiple personalities. More generously, you could say that it’s not just peppered in to look mature or add shock value, but an integral part of her character. She is, after all, inspired by the nominal true story of Truddi Chase, who writes in When Rabbit Howls that she also developed multiple personalities after being raped by her father as a child. But the tasteless, over-the-top luridity of Morrison’s approach to the sensitive subject matter tells another story. This year’s journey into Jane’s consciousness in “Going Underground” alludes to a second rape, and a later story would reveal that not only would Morrison go on to pile on more trauma to her past, she was raped by a homeless man! In a church! On Easter! And then she killed him! Like his peers, Morrison takes gritty realism so far it cycles back around to being cartoony again.