“The priest told me it’s not a sin to kill if you don’t enjoy killing. My question is whether indifference is the same as enjoyment.”

“All religious stuff aside, the fact is, people who can’t kill will always be subject to those who can.”

Dear Frederick, thank you for your nice letter, but I am actually a U.S. Marine who was born to kill whereas clearly you have mistaken me for some sort of wine-sipping Communist dick-suck. And although peace probably appeals to tree-loving bisexuals like you and your parents, I happen to be a death-dealing, blood-crazed warrior who wakes up every day just hoping for the chance to dismember my enemies and defile their civilizations. Peace sucks a hairy asshole, Freddy. War is the motherfucking answer.

Generation Kill is straight ground reportage of a slow-motion global tragedy and one of the many things it gets right is the way regime changes, horror, and failure all get felt as fuck-ups and comedy as much as anything else. It’s an immensely funny, immensely quotable show. Its characters drive in their broken-down Humvees and sing off-key renditions of “Teenage Dirtbag” and “King of the Road” and give each other endless, creatively profane shit. They enjoy each other—Simon often lets the camera linger on one soldier reacting to another, a smile gradually and beautifully emerging. It’s a workplace comedy complete with inept bosses and petty schemes. It’s just a workplace comedy where the inept bosses result in catastrophic civilian casualties, tattered infrastructure, and disillusionment. Joke’s on—well, not us. A pretty good working definition of empire is that the joke is always on someone else. Shit rolls downhill all throughout the series, from generals to lieutenant colonels to captains to lieutenants and sergeants… and from there on to the people of Iraq.

It’s a cynical comedy, but still a comedy, one in which the social order will ultimately win out and keep rolling on. Simon ratcheted The Wire up to drama by splitting his cast, making one side struggle against the other to not be the ones buried in the shit as it comes downhill, but that’s not the structure here. We’re only on the one side. Simon is interested in the Problem of America, and so it’s America that Generation Kill is concerned with: a country of high ideals, bloody history, good music, and a completely baffling self-image.

The series puts us with a platoon of First Recon, Marines who specialize in infiltration, observation, reconnoitering, and precision. (Here, they’re used to barrel in unprotected as a ground invasion: “finely-tuned Ferraris in a demolition derby.”) Evan Wright (Lee Tergesen), a reporter with Rolling Stone, gets embedded in Bravo Company and hauled around by Sergeant Brad “Iceman” Colbert (Alexander Skarsgard), Corporal Ray Person (James Ransone), and Lance Corporal Trombley (Billy Lush). The duration of the show is roughly the duration of Wright’s stay, and his role on the show is oddly and touchingly restrained—like the journalist he is, he gets out of the way of the story. He asks a few audience surrogate questions to get Marine slang passed along, but mostly, Simon just immerses the show in these guys’ particular diction and concerns and trusts the viewer to either figure it out or deal with not knowing. Wright isn’t a catalyst, and he shakes nothing up. He’s just there, fond and funny and inexhaustibly attentive to what he’s being given; a character rather than a device. The Marines balk at him at first, but cheer up once they find out he used to write for Hustler. They eventually wind up treating him as a kind of pet, casually looking after him and always willing to feed him if he wanders their way.

“Technically speaking, Brad, but didn’t your biological parents disown you when they put you up for adoption?”

“Point, Ray. I was one of those unfortunates adopted by upper middle-class professionals and nurtured in an environment of learning, art, and a socioreligious culture steeped in more than two thousand years of Talmudic traditions. Not everyone is lucky enough to have been raised in a whiskey tango trailer park by a bow-legged female whose only qualification for motherhood was a womb that happened to catch the sperm of a passing truck driver.”

“At least my mom took me to NASCAR!”

Brad, Ray, and Trombley are directly commanded by Lieutenant Nate Fick (Stark Sands), who is directly commanded by Encino Man (Brian Wade). Fick is smart, principled, fundamentally decent, and devoted to his men; Encino Man never rises above the level of competence necessary to dress himself. In the midst of all this, you have “Captain America” (Eric Nenninger), a skittish, trigger-happy buffoon with the anxious face of a kid perpetually on the verge of realizing that no one actually likes him. Above them all, “Godfather” himself (a gravelly-voiced Chance Kelly), a lieutenant colonel whose dignity and probable skill temporarily masks his bottomless desire for advancement and the approval of General Mattis.

Brad, Ray, and Trombley themselves make up a triptych of highly-trained, highly-capable soldiers. Skarsgard excels as Brad—for pure sex appeal, most people can never top their louche vampire roles, but Skarsgard is at his most irresistible here, a gorgeous, still center, sharp-eyed, sharp-witted, ruthlessly geeky, loyal, and dangerous. Ray is a lovable, irritating mess—Ransone plays him as though he always has food on his chin and half the time, he does. Tasked with driving the team’s Humvee for unpredictably long stretches of time, Ray spends the series hopped up on high-octane caffeine and talking relentlessly, always needling and questing and joking and yet never missing a step. The two of them have the lived-in banter of a long-time married couple (partly featured above).

“Sergeant, I didn’t get to shoot!”

“That fucking sucks, Trombley. Did your recruiting officer tell you you’d get to shoot people?”

“Fucking A he did!”

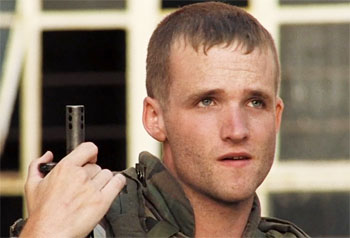

Trombley, on the other hand, is an outlier, and one of the show’s best elements. He’s flawlessly good at what he does, making shots few others could make, but there’s a gaping hole at the center of him. He joined the war to kill people—if he can’t kill people, he wouldn’t mind killing dogs. He joins conversations belatedly and at odd angles, color-blind to the cues of ordinary human interaction. Lush has the baby-faced, always slightly sulky look of a born school shooter. Trombley is young, and Lush plays him young, often imbuing him with a kind of otherworldly innocence—he’s too far off the grid to bear moral responsibility or feel moral experience. He just is. When he’s allowed to, he kills children.

One of my favorite off-kilter moments with him is when, in one of the show’s typical discursive bullshit sessions about race—in this case, the possibly American Indian, possibly not Poke criticizing Pocahontas—Trombley perks up at the mention of Indians like he’s just recognized a word. Right then, he’s Steve Rogers: “I understood that reference.” And what does he pitch in? “My great-grandfather killed Indians. Up in Canada, for money.” Poke, incredulous, gives this a wary respect: “Most white motherfuckers that talk about their people, they say they got a Native American ancestor. Pretend to be down with me. But here you are coming the other way.”

Here he is, always, coming the other way.

But if Generation Kill has a thesis, it’s this: you can live with a Trombley.

Trombley is amoral and deadly, but he’s a flawless soldier. When he kills the two shepherd boys, it’s because the rules of engagement have given them permission to fire on everything within that zone; when he doesn’t have that permission, he doesn’t fire. (A nice touch is that Brad, who feels the weight of the deaths in a way that Trombley literally can’t, takes responsibility for this: he knew what Trombley was and he told him about the change to the ROE anyway.) Trombley may respond to carnage by getting a hard-on, but that same loose screw means that he’s the one to stand up during a seemingly unstoppable barrage to admire the fire they’re taking… and pinpoint its source so they can knock it out. “I just get more nervous watching a game show at home on TV than here, in all this, you know?” he says afterwards. He’s fearless. His big moment of gratification is being told, at last, that they’re shooting wild dogs—“See, Sergeant, we do shoot dogs in Iraq,” he says, and, grinning, bites into a packet of Charms, the bad-luck candy he’d been previously barred from. Unsure, but choosing the direction he’s going to go in, Brad smiles back. Trombley’s one of them.

So your problem in war isn’t psychopathy but incompetence. Even in the land of no-asses, the half-assed man would not be king. The men tolerate the “illiterate fucking retardese” of Sgt. Major Sixta, who chews them out for the length of their mustaches and their untucked shirts, because he’s there for a reason: “Sgt. Major Sixta’s job is to be an asshole. And he excels at the position.” The men tolerate mistakes, which are made by everyone. What they hate is amateurs—the reservists who swoop in to mess everything up and put antlers on their Humvees—POGs (persons other than grunts), and, above all else, idiot officers.

“We’re out here, forty clicks behind enemy lines, and this man of God here, he’s a fucking POG. In fact, he’s an officer POG. That’s one more layer of bureaucracy and unnecessary logistics, one more asshole we need to supply MREs and baby wipes for. And worst of all—worst of all—the motherfucker doesn’t even carry a weapon. When push comes to shove even Rolling Stone picks up a gun but this fucking shill of God, he can’t cover a sector. He’ll never hump ammo or Claymores.”

The sins of Bravo Company are, in ascending order: not doing your job, fucking up your job, and fucking up someone else’s job.

Encino Man accidentally calls in artillery strikes that could kill his own men and gets away with it only because he gets the coordinates wildly wrong. Working beneath him just saps Nate Fick’s will to live over the course of the miniseries—every episode, you can see a little more of the light go out of his eyes as he has to deal with being called a coward for trying to block his CO from getting them all killed. Early on, when his men slightingly refers to Captain America, Nate cuts them off—“If you have a nickname for an officer, I don’t want to know it”—but by the end, he doesn’t even blink at it. He’s one of the most respected officers on the show—every scene he shares with Skarsgard is an implicit lesson in use of eye contact, consistently establishing Brad’s genuine loyalty and deference, putting it on screen even before Brad has to spend time tracking down the gossip against Nate and try to quash them.

“Sir, your leadership is the only thing I have absolute confidence in,” Brad says to Nate; meanwhile, the best Nate can do with Encino Man is, “Respectfully, sir, I have only ever tried to interpret your intentions to the best of my ability.”

That’s the harshest he can afford to get, but Doc Bryan, the caustic Bruce Banner of the unit, accidentally gets permission to speak freely: “Well, sir, it’s just that you’re incompetent, sir.” “I’m doing the best I can,” Encino Man says. Bryan doesn’t even blink: “Sir, it’s just not good enough.”

Weakness and incompetence gets innocent people killed: as Brad says, it wastes the victory.

Equally dangerous is Captain America, buffoonish, terrified, and so desperate to be brave that he’s over-the-top aggressive… so long as that aggression can be directed against, say, a bound and restrained prisoner or an abandoned vehicle. “Denying the enemy transportation!” he chirps as he wastes ammunition destroying a car. He steals Ak-47s off dead Iraqis and fires them off into the night when he freaks out—sometimes while crying over the radios—which leads to the breaking point when one of his men just has to confront him:

“Sir, it’s about the enemy AKs you’ve been firing from your vehicle. You’re endangering us. You’re not calling your targets. The AKs sound like enemy fire… Respectfully, sir? You fire an AK one more time, I’ll fuck you up.”

Workplace shows understand the community as a social unit. Generation Kill gets that Bravo Company can accommodate a Trombley alongside an Iceman. You can have a Rudy Reyes—Reyes plays himself, because the man is a human unicorn no one else could hope to impersonate, a serene warrior Adonis who talks dreamily about finding his true dharma. You can have Ray Person—“the best RTO in the business, as long as you keep him away from your uglier daughters and your smaller livestock.” But you can’t work with a Captain America or an Encino Man. You can’t work under a Ferrando, whose idea of a real coup is gaining a mission to seize an airfield… before British allies can seize it first and get the credit. When Wright talks to him before he finally exits, it feels like a reckoning that can’t quite be achieved: Ferrando isn’t stupid, but he has a carelessness Wright can’t penetrate, and that carelessness, combined with his vanity, is deadly.

“You want logistics, join the Army,” Nate says early on, smiling. “Marines make do.” And they can deal with that—Semper Gumby, they say, “always flexible”—they can deal with inexplicable rules that allow stores to be sold in bulk to civilians but not to military personnel, they can deal with woodland-camo in the desert, they can deal with slow mail. The broken-down equipment takes more of a toll. The top-down idiocy, though, takes the most: as one of the men puts it, “If they say we fought valiantly, I want them to know that we fought retarded.”

So it’s all on the record in the end, wrapped up by one soldier’s documentary video of the invasion thus far, scored to Johnny Cash’s “The Man Comes Around.”

There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names

And he decides who to free and who to blame

Everybody won’t be treated all the same

Nate leaves first. He’s done. The footage lets some of the interpersonal conflicts patch themselves up. In the end, there’s just Trombley, watching, his face aglow: “It’s fucking beautiful.”

When you do war this badly, the only purpose anyone can find is death. Everyone not in it for that leaves early.