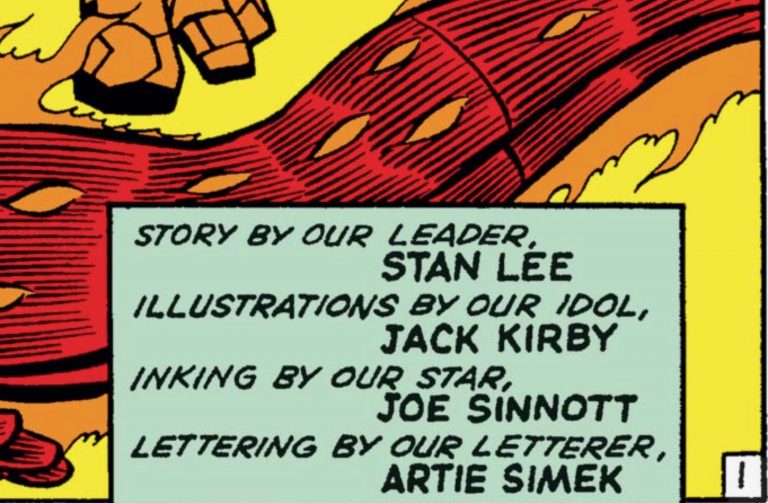

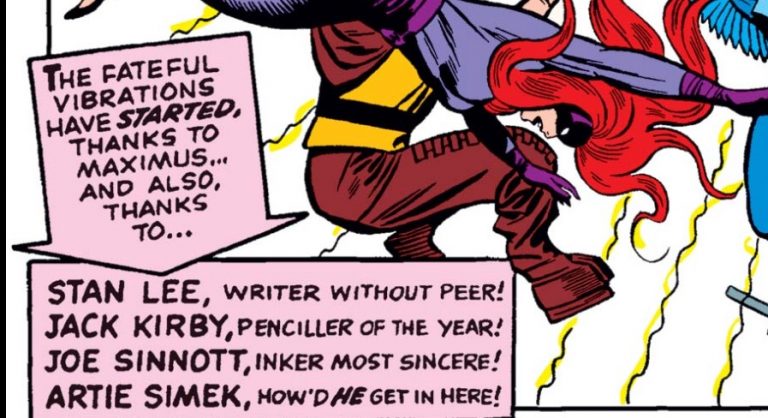

Fifteen years ago, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four stories of 1966 were my introduction to the world of superhero comics. Thanks to my art teacher’s extensive comic collection, I’d already gotten into the humor/superhero hybrids like Captain Marvel (the other one) and Plastic Man, but thanks to the parodies of the dour and edgy comics of the nineties in Calvin and Hobbes and others, I thought the rest of the genre was nothing but a humorless gorefest. After all, if the books I liked were “humor” comics, doesn’t it stand to reason that the rest must be humorless? So I was shocked by Fantastic Four’s deft and often hilarious integration of comic relief through its smart-mouthed team muscle the Thing and Stan Lee’s fourth-wall-breaking and even downright parodic narration. I can tell you that twelve-year-old me thought the credit boxes that build in breathless hyperbole to bag on the poor letterer were the funniest thing in the world.

It was also how I learned the meaning of a word I’d seen in the vocabulary of media appreciation but never really understood – “exciting.” Fantastic Four, along with Star Wars and Jeff Smith’s comic Bone moved me from the kiddie table to the world of real action with real stakes – something I’d previously been too immature to enjoy, actively avoiding it because it made me uncomfortable. I can see now that the reason Fantastic Four made that impression on me is Jack Kirby’s restlessly dynamic artwork, all heavy foreshortening and dizzying angles. And his plots, co-created with Stan by the “Marvel method,” match the art’s relentless forward momentum – like the early episodes of Tintin and the early newspaper-comic serials I loved so much at a time, Fantastic Four seemed to be one huge story stretching out over years.

That was revolutionary when it first came out – one reader complained that the three-part Galactus storyline was too long, and oh, buddy, have I got some bad news about the comics of the future…But the meticulously pre-planned, years-long storylines of later writers like Grant Morrison and Jonathan Hickman can’t match Stan and Jack’s one-darn-thing-after-another – and Stan freely admitted in the letter pages that he and Jack were flying by the seats of their pants, with no idea where they’d end up.

As a result, 1966 begin mid-story, as the Fantastic Four (Reed Richards, the rubber-limbed supergenius Mr. Fantastic; Sue Storm, his wife and the Invisible Girl; her brother Johnny, the Human Torch; and the monstrous Thing) have discovered a hidden family of Inhumans, people who had developed genetic engineering in prehistoric times and now had incredible powers. A stoic character with baller shades and an equally baller mustache is hunting them down to take them to the Great Refuge somewhere in the Himalayas.

It’s a very YA-y plot of a hidden world of people with incredible powers living among us that I ate right up as a child. (This was before their abilities were retconned to come from the alien Kree.) More importantly, it’s a showcase for Jack Kirby, whose design sense was really coming into its own in his third decade of comic art. With the Inhumans, he had the chance to design a whole world of settings, props, and costumes that would make any Hollywood production designer green with envy. The comics are full of his unique style: futuristic designs overlaid on ancient forms, covering abstract shapes that are all Kirby. When I first read this, I thought it was a flaw that everything looks futuristic, even the preserved medieval knight Johnny meets later on. Now I see that’s just Jack’s unique style, and seeing it overlaid on different settings and genres is one of the greatest thrills of his work.

From there, it goes to an even greater showcase for Jack’s imagination, maybe the greatest he ever got: The Coming of Galactus. The title character is a work of gonzo ingenuity, dressed in ornate, bright-purple armor including a tuning-fork-flanked helmet that looks like it weighs more than his head, Galactus is a cosmic being who travels the universe, consuming planets’ energy and leaving barren husks behind. He was a threat at a scope comics had rarely seen before – there’s an urban legend that the story came about when Stan decided to pit the FF against God Himself. Kirby’s assistant and biographer Mark Evanier gives a more mundane origin story – Jack had been inspired by reading in his stocks about corporate raiders who would strip companies for parts and leave the shell behind.

It was mind-blowing at the time, but comics have built on it so much on its foundation it can be hard to see how groundbreaking it was. Now the Marvel Universe is filled with a whole cosmology of unearthly powers, many of whom have taken down Galactus like a chump. Even the eater of worlds himself looks puny compared to future artists’ interpretations of him, a mere three or four times human scale instead of towering several stories high. But the idea was there: here was a threat that could make even superhuman heroes look like helpless underdogs.

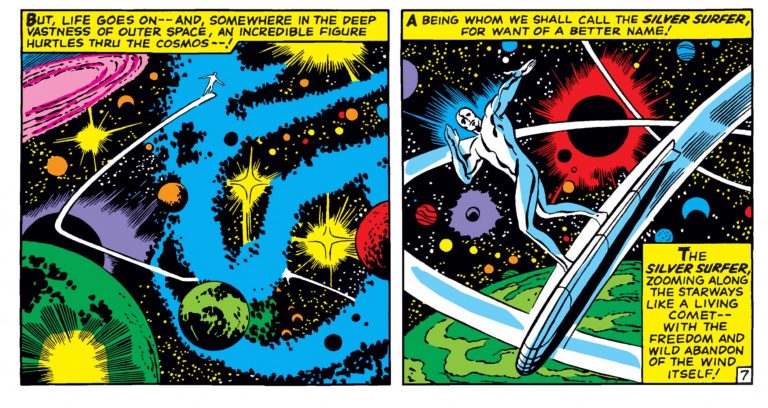

The Coming of Galactus is a masterwork in building tension. Jack pulls out from the Inhumans’ Refuge to the depths of the cosmos, which he presents not as empty “space” but a dynamo of crackling energy and whirling galaxies, where we see Galactus’ unearthly “herald.”

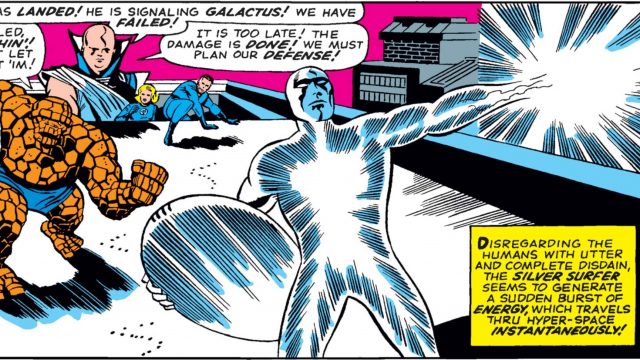

The Skrulls, who had been major threats in their own right in previous issues, are so terrified they “order the entire Skrull solar system blacked out at once!” The story only gets more ominous from there, when, in an image worthy of a biblical apocalypse, the sky literally turns to fire. This turns out to be the work of another cosmic being, the Watcher, who has sworn never to interfere with life on earth unless the threat is very grave indeed. (That last bit would have had a little more impact if he hadn’t constantly interfered in his previous appearances, even to shoo a bunch of supervillains away from Reed and Sue’s wedding.) Despite his efforts, the herald touches ground and summons Galactus, who finally appears on the last page (in a color scheme that fortunately wouldn’t last through his next appearance).

But who is this herald? Stan knew less than anybody when he sat down to write the issue. He was more or less Marvel’s sole writer during this period, and so, to handle his workload, he developed the “Marvel method”: he and the artist would conference about the plot, and then he would write dialogue over the finished artwork. In this case, though, he found something they’d never discussed: “The thing came back and I could hardly wait to start writing the copy. All of a sudden, as I’m looking through the drawings, I see this nut on a surfboard flying through the air. And I thought, ‘Jack, this time you’ve gone too far.’”

Most fans would agree Jack had gone just far enough. Sure, the character was goofy on the face of it. My aunt once caught me reading an old Marvel Handbook and asked, “The Silver Surfer? Is this for real?” Even in the finished story, Stan is tentative, calling him, “A being whom we shall the Silver Surfer, for want of a better name!” But the grace of Jack’s imagery and of his character steamroll over any of our goofy stereotypes about surf culture. And his arc, as Alicia Masters, blind sculptor and love interest to the Thing, teaches him the value of life and turns him against his master, is one of the most powerful the series ever had.

Despite his initial resistance to the character, Stan became very possessive of the Silver Surfer. While Jack was working on an origin story for his creation, Stan had his own ready as he launched the character into his own series with artist John Buscema. In Stan’s version, the Silver Surfer was once a man, Norrin Radd of the planet Zenn-La, before Galactus chose him as a herald. This made no sense in light of his first appearance, and Stan awkwardly tried to handwave the inconsistency.

Despite his limited role in the Surfer’s creation, Stan was still possessive over him, not allowing any other writer to touch him for decades. As for his primary creator, the whole experience was yet another wedge in his increasingly fraught relationship with Stan Lee. After this incredible fertile year – before it was over, he’d created not just Galactus and the Silver Surfer, but also the Black Panther, his enemy Klaw, and, in the pages of a few of his many other books, Ego the Living the Planet and the persistent evil empire of A.I.M., Jack saved all his new ideas for himself, preferring instead to recycle villains from past stories, or from other media, as when he turned The Creature from the Black Lagoon into the Lost Lagoon Monster. In the words of his wife Roz Kirby, “No more Silver Surfers until he gets a better deal.” He’d spend the rest of his career looking for it.

Want to help BurgundySuit find a better deal? Then donate to his Patreon!