In 1925, a major railroad accident took place in the Soviet republic of Georgia, causing a fire that raged for several days. On the second day of the chaos, police arrested a pair of suspicious individuals who had been shooting the disaster for hours with foreign-made film cameras for hours. The suspects turned out to be not spies but filmmakers: director Lev Kuleshov and his student Mikhail Kalatozov. From then on, the young Kalatozov knew he would walk through fire to get the best shot.

Kalatozov had many jobs in his early years, working as a movie-studio driver, an actor, and a cinematographer. His proficiency as a cameraman would prove especially useful later on: a tireless craftsman, he would be among the first Soviet filmmakers to use his own camera filters and put the camera on a moving platform. In 1928, at the age of 25, he directed his feature debut. Their Kingdom, a five-hour silent documentary made in collaboration with Georgia’s first female filmmaker, Nutsa Gogoberidze, was praised for its unconventional approach to chronicling historical events. With an acclaimed feature under his belt, Kalatozov was now ready for a solo outing.

By that time, the USSR was in the midst of its first five-year plan, and the Soviet film industry was considered the most effective tool for trumpeting the hardworking nation’s latest successes. Svanetia, a region of Georgia saddled with poorly developed infrastructure due to its isolation by high mountains, provided a great opportunity to compare and contrast the old way of life with the purportedly unstoppable advance of progress. After commissioning a script from writer/journalist Sergei Tretyakov, Kalatozov arrived in the mountain village of Ushguli to shoot his film. Originally titled The Blind Woman, it was supposed to be a silent drama about the life of the Svan people. The story goes that the dailies were criticized for “formalism,” and Kalatozov opted to re-edit the footage into a silent documentary. (Some sources claim that it was cobbled together by none other than Viktor Shklovsky, but there is scant evidence to support that claim.) The resulting film is an hour-long blend of fact and fiction showcasing Svanetia’s vertiginous landscapes and Kalatozov’s prowess as a visual thinker.

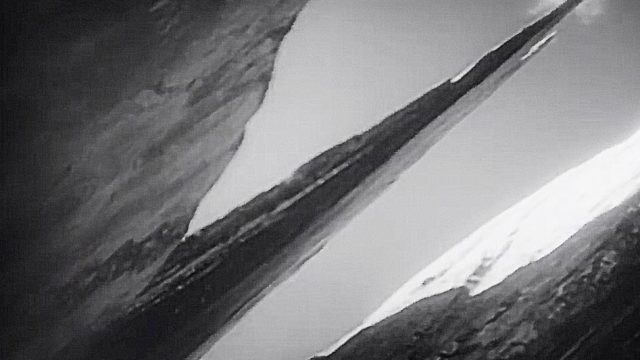

Like many films of that era, it begins with a quote from — guess who? — Vladimir Lenin and a brief description of Svanetia’s sorry state. A map of the region is followed by footage of snowy mountains, rivers, and fortresses. The Svan people have always built fortresses to defend themselves from tax-hungry barons, we are told. This is shown in the first of the film’s startling reenactments: a local man throws boulders from the top of a tower to fend off invaders, and the camera follows every movement, soaring to the sky and plummeting to earth. Kalatozov and co-cinematographer Shalva Gegelashvili use each set-up for maximum emotional impact, bathing the frame in deep shadows and employing canted angles and dramatic close-ups. “A camera angle need not make a subject look beautiful or original; it should be used purposely as a stylistic device informed by the idea of the work,” the director wrote, and yet the film is powerful precisely thanks to its dynamic, vivid imagery that makes the most mundane goings-on look exciting.

The bulk of the film is devoted to the villagers’ routine activities: they raise sheep, card wool, grow barley, and give each other haircuts. The land is inhospitable (“stone, stone everywhere as long as they live”), the work relentless and numbing, the climate harsh and unpredictable. In one sequence, a snowstorm breaks out on a hot summer day, and people desperately try to salvage the harvest as their elders pray for the sun to return. In another scene, a group of men sets off on a journey, and the image of black figures against a snowy expanse calls to mind depictions of the danse macabre.

The villagers’ biggest problem, however, is the lack of salt. Since the only way to obtain it is to travel across mountainous terrain to the neighboring valley, villagers constantly risk their lives to bring home salt while people and animals struggle to make do without it. The struggle is illustrated in a series of disturbing scenes showing animals licking human sweat and urine (“urine contains salt,” an intertitle notes helpfully). The lack of salt is posited as the ultimate proof of the unsustainability of the traditional lifestyle. This point is further emphasized when we see reenactments of some ancient customs (the authenticity of which was disputed by the locals): a rich man’s funeral, which involves theatrical lamentations and animal sacrifice, and the banishment of a pregnant woman whose condition is considered filthy. In the film’s most harrowing scene, a despondent mother mourning the death of her newborn squeezes her breast, and her milk drips onto the infertile ground — a potent metaphor for fruitless labor wringing people dry.

This bleak and intimate portrait of a community is so convincing that the triumphant finale feels perfunctory. About five minutes from the end, a cadre of young, feverishly agitated builders appears out of nowhere and constructs a road to connect Svanetia with civilization. Although the final sequence is punchy and visually interesting (and the way the builders are shot rivals Eisenstein in its unspoken homoeroticism), its tone clashes with the solemn, mythical exploration of man and nature that precedes it.

While contemporary reviews pointed out the incongruity of the ending, Salt for Svanetia was successful with critics, and Kalatozov went on to have a great career, eventually winning the USSR’s first and only Palme d’Or for The Cranes Are Flying. His evocative, distinctive visual style continued to evolve, reaching astonishing highs in the frontier drama Letter Never Sent and I Am Cuba another film that compensated for its blatant ideological messaging with head-spinning camera acrobatics. As for Svanetia, salt shortages are no longer a problem for its people. In fact, Svaneti salt — a mixture of salt and sundry other spices concocted by the locals to make their salt supplies last as long as possible — is now a popular delicacy sold at high prices in other regions.