This review contains SPOILERS.

Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail is a profoundly sad and deliriously funny road movie. It’s also a movie about family units – how much we need them, cherish them, and ultimately how much we debase ourselves and others to keep these units functional. Notions of proper chain of command and loyalty, along with the infinite joys and perils of compassion – these are implicitly and explicitly explored throughout, but most basically The Last Detail is a simple story about masculine rites of passage, rendered with emphases on profane poetry and the soft underbellies of a certain type of man. It’s one of the most moving, yet least sentimental films of its decade, and the way it manages to balance these considerations remains staggering forty-eight years later.

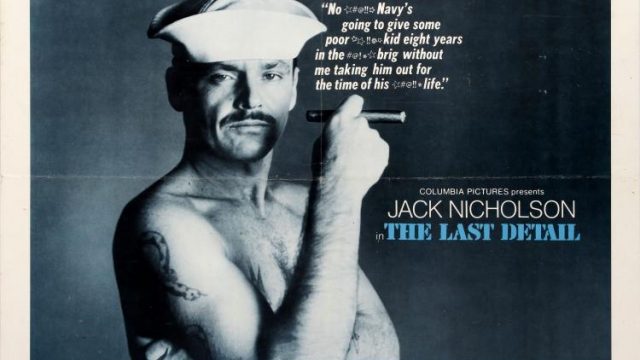

Our two main characters are, ostensibly, sailors in the U.S. Navy, though none of the film takes place on a boat or even very near water. Quickly we get a sense that the Navy has brought a sense of order to their lives, and that order is something they’ve come to count on. The Navy provides a family’s stability, and so, protests about “not going on no shit detail” aside, when “Bad Ass” Buddusky (Jack Nicholson) and “Mule” Mulhall (Otis Young) are tasked with escorting a seaman to the brig, they grouse, but they follow orders. As Nick Nolte’s Colonel Tall puts it in The Thin Red Line, “The only time you worry about a soldier is when he stops bitching.”

The shitbird in question is Larry Meadows (an impossibly boyish Randy Quaid). His crime: stealing forty dollars from the polio contribution box. His punishment: a dishonorable discharge and eight years in Portsmouth Naval Prison. (The shake-your-head excessiveness of this – “Eight years and a D.D.” – becomes one of the film’s most sobering refrains.) As the chief (Clifton James) tells them, the wronged charity is “the old man’s old lady’s favorite do-gooder project,” as if that says it all. Right away The Last Detail seems like it’s going to be a very 1970s type of film – a bracingly cynical look at military injustice through the eyes of a couple of old salts.

Throughout the film the trio hits several cities in the northeast, and gradually Meadows goes from being the shackled, dour face of doom to a jovial, slightly less naïve young man. It’s very much a family road trip, with the smaller unit of Buddusky, Mule, and Meadows testing each other, and the limits of their larger family – the Navy itself. The two men – but particularly Buddusky – take it upon themselves to give their charge a crash course in overtly masculine conduct circa 1973, mostly in the form of object lessons in assertiveness and playful misbehavior. Their hijinks give rise to a strange and profound sense of intimacy between the three.

The thaw between prisoner and captors begins when the latter catch Meadows hiding some stolen groceries up his sleeve (if you’re watching carefully, you’ll see him make the lift from a lady’s shopping cart). Realizing he’s caught, Meadows leaps out of his seat on the train and makes a run for it. It’s a child’s pure flight response, and even though the two sailors are annoyed at having to chase him, how could anyone stay mad at Randy Quaid sobbing through these lines?

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry for stealing the money. I swear I didn’t want it. I’m always stealing junk I don’t need. Quart bottles of hair tonic, model cars. I can’t even build a model car. Just crap. You know? I had money on the books – you can ask anybody. But it’s gone now ‘cause I got forfeiture of pay and everything. But I had money.”

This is probably the most important moment of Quaid’s performance. It confirms that, more than just looking young, he is young – young in experience, young in terms of self-awareness, so young that the notion of throwing him into a jail cell seems criminal in itself.

Mule is perturbed: “Jesus. The kid’s crazy.”

Buddusky concurs: “He’s a fuckin’ mess.”

The pair’s plan to rush the kid to the slammer and pocket a week’s worth of per diem quickly falls awry. Taking him off the train to “walk him around a little bit” and calm him down leads to a cheeseburger and Buddusky Lesson #1: “Have it the way you want it.” This is an interesting counterpoint to another famous “Jack Walks into a Diner” scene, resolved much more amicably: “Melt the cheese on this fer the chief here, would ya?” And honestly, what fucking restaurant doesn’t melt the cheese on a cheeseburger?

This leads fairly organically to Buddusky Lesson #2: “Everybody’s old enough for a beer. Ain’t that right, Mule?” Unfortunately the bartender is a racist asshole, hiding behind liquor laws to refuse service to Meadows (who’s too young) and Mule (who’s too black). So you pull your gun and start screaming at him. As with the disappointed order of toast in Five Easy Pieces, this reaction does not result in said beer, but the trio is so jacked (tee hee) in the wake of the confrontation that they giddily vow not to leave D.C. until Meadows has “a bellyful of beer”.

They miss their train and hole up in a motel room, heroically guzzling Schlitz all night like good sailors on liberty. Buddusky is one of the screen’s great drunken assholes in this scene, playing several different kinds of bad father to Meadows’ son: first, he wants to school the boy in semaphore, and gets close to maudlin when he does so well on his first try; then he lashes out at Meadows for not being tougher, or not being at least a bit angry at the injustice of his situation; finally, he’s despondent and can’t be bothered with the kid, culminating in a splendidly heartfelt reading of the line, “I don’t give a shit,” cigar miserably lodged in the corner of his mouth. In the midst of this revelry, we get Buddusky Lesson #3: “Don’t you ever just want to fucking romp and stomp on somebody, just bite off their ear – just to do it, just to get it out of your system?”

The increasing closeness of the group takes an interesting turn when Buddusky suggests they go with Meadows to see his mother, who’s only a couple of hours out of the way. Meadows spends the trip pointing out landmarks from his past and reminiscing about his teachers and his childhood, but the camera mostly stays on Nicholson, his face either impassive or despairing. The camera moves even closer when Meadows begins speaking about his absent father, and it’s fascinating to watch the subdued reactions of Buddusky, his present father. In the end mom isn’t home, and (saddest of all) this is probably a good thing: when they finally try the door, it’s open, and the den is the squalid mess of a full-throttle alcoholic. “I don’t know what I would’ve said to her anyway,” Meadows reflects.

On the return trip, Lesson #3 is made flesh in the form of a bunch of Marines in a train station bathroom. They gently provoke Buddusky, who escalates things, flashes a smile, and there’s a quick, fairly painless brawl that ends with the trio celebrating their success (particularly Meadows’) with “the finest Italian sausage sandwiches in the world” and a few Heineken. Buddusky Lesson #4: “It’s the finest beer in the world, kid. President Kennedy used to drink it. Huh? Huh?”

After a spirited and clumsy bout of ice skating, Quaid’s gangly limbs flailing with abandon (“He looks like a goddamned big penguin, don’t he?”), the trio stumbles upon a Nichiren Shoshu chanting party (Gilda Radner and Derek McGrath – Crazy Andy from Cheers – notably in attendance). It’s here that Meadows learns about Nam Myoho Renge Kyo and the Gohonzon (“What’s a Gohonzon?” “Shh. I’ll tell you later.”), and he takes up chanting with a zealous fervor. As the saying goes, there are no atheists in foxholes, and while it might seem that Meadows is merely trying to imitate the cool kids – again, in a very 1973 way – he also seems desperate for something meaningful enough to get him through his coming trials, or even powerful enough to deliver him from them.

Next, having been hitherto unsuccessful in their endeavors to make this happen organically, Buddusky and Mule decide to get Meadows laid.

In the waiting room of the whorehouse, the notion of family goes from subtext to text again. Buddusky says he was married once, but that he couldn’t handle his wife’s idea of domesticity: “fixing TVs out of the back of a VW bus.” Mule supports his mother, and clearly enjoys how much pride she takes in his accomplishments. Buddusky’s resigned observation, “Guess we’re just a couple of lifers,” brings to mind a line from The King of Marvin Gardens, which Nicholson’s character delivers to his flamboyant fuck-up brother: “We’ve all done our time, Jason.”

We’re spared most of Meadows’ encounter with young Carol Kane, apart from an obligatory gag about premature ejaculation, and a short dialogue between the two in the aftermath of a second round, courtesy of his benevolent benefactors. Kane’s prostitute has difficulty meeting his eyes, but the look on Meadows’ face carries the hopelessness of a boy who’s only just discovered girls, and who knows he won’t be seeing another one for a very long time. Both actors do terrific, nuanced work, and this scene is typical of Hal Ashby’s approach: he holds on a single medium shot, avoiding cutting to sustain the intimacy.

Ashby came up as an editor, proving his mettle in works like In the Heat of the Night, and his natural sense of rhythm is an important part of The Last Detail’s success. In collaboration with Robert C. Jones, he uses slow dissolves from faces to landscapes to effectively communicate the terminal boredom of the time spent on buses and trains. His jump cuts in the motel room bender sequence are some of the funniest elliptical edits in film history (smashing from Buddusky’s tantrum about stomping “grunts” for the hell of it, to him moping miserably on the edge of the bed as Meadows good naturedly asks him for instruction about “hand signals” is pause-the-movie hilarious). But most importantly, as described above, Ashby has the sense to hold on the faces, usually in medium shots, and often more than one face at a time. He sometimes holds even longer than might seem useful, having the patience to wait for the humor or sadness to reach its apex. As an example, look at how long he lets Nicholson do his unseemly “yodeling in the canyon” cunnilingus routine as Quaid goes upstairs with a young lady: it gets funnier and more tasteless each time.

The group’s final outing, a picnic, captures a certain kind of feeling that will be familiar to anyone who, as a child, found Sunday evenings slightly melancholy: the holiday’s all-but over, but families sometimes feel compelled to make plans. So Meadows, Mule and Buddusky go to a miserable, frozen tundra of a park and cook hot dogs over a hobo fire. Buddusky forgot to get buns, prompting the most transparently marital spat of the film, with Meadows acting as mediator for his warring parents, dipping the dogs directly into the mustard and assuaging mom and dad: “It ain’t bad.” It’s clearly colder than hell (watch Nicholson’s trembling hand as he lifts the can of beer) and Meadows wanders some distance away, chanting for the strength the break a frozen branch and, it’s assumed, his freedom. Buddusky lays it on the line:

“He don’t stand a chance in Portsmouth, you know. Goddamn grunts kicking the shit out of him for eight years? ‘Maggot’ this and ‘maggot’ that.”

Mule doesn’t want to hear about it, but it seems as though Buddusky is considering letting the boy go. Then Meadows takes off, again, and Buddusky channels his rage in exactly the wrong direction, bashing the boy about the head with near-homicidal rage.

Buddusky’s Final Lesson goes unspoken. After doling out the pistol whipping, he and Mule deliver Meadows to Portsmouth, then silently stand by and watch him led away, whimpering and bleeding. If you want an object lesson in “less is more” filmmaking, you could do a lot worse: there’s no saccharine music, no meaningful close-ups, no words (or even looks) exchanged between Buddusky and Mule. So devastating is this moment that we only need to see, in the most basic sense, what’s happening. It’s the bitter fruit that The Last Detail has been not-so-secretly waiting to harvest all along; the viewer has been content to marvel at the film’s astute observational comedy, and now we hear the jaws of the trap (and the clang of the cell door) slam shut.

Michael Moriarty shows up as the officer-in-charge and chews the pair out for beating Meadows, and for their part they stay mum about the prisoner’s pathetic escape attempts, knowing that it will only make his situation more dire: his “not really eight years” will become eight years. Moriarty is a useful diversion: his bureaucratic incompetence allows Buddusky an opening to rant and rail about “candy asses” who don’t understand the importance of redundant paperwork. Meadows isn’t mentioned again.

Do you have a favorite Jack Nicholson performance? In my experience, most people do. He’s the kind of actor who manages to be towering and intimate, and his range is remarkable. The last time I watched One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, during a key scene towards the end of the film, I realized that my facial expressions were unconsciously mirroring Nicholson’s own reaction to the events on screen; over the previous two hours, his humanity had become a guiding light for my own responses – or, my responses were purely visceral, and he’d anticipated them years earlier.

The Last Detail was part of a deluge of noteworthy screen work that Nicholson produced in the 70s, but I think what makes this Nicholson performance my very favorite is the way it takes the angst of an unexamined life in Five Easy Pieces and marries it with the “fuck authority” fire of Cuckoo’s Nest. Buddusky is not a particularly literate or insightful protagonist, but Nicholson imbues him with a captivating worldly sauciness, and punctuates this with moments of avuncular warmth and, occasionally, white hot rage.

Robert Towne writes for Nicholson like no one else, probably because the two had been friends, and the former knew better than anyone how to authentically capture “the voice”; just how much of the dialogue was on the page and how much was improvised is uncertain. It certainly feels more “of the moment” than not, and the lack of apparent worry about overlapping or muddled dialogue adds to that impression (particularly during the motel room bender), but maybe that’s just Towne’s genius. However the division of labor is split, the Towne/Nicholson alchemy manifests itself in moments great and small, and I’d need to transcribe the entire movie to do it justice; here is just a sample of The Last Detail’s glories:

- Buddusky’s inability to get Mule’s name right: “Ain’t that right, Mulhand?” and even better, “Where’re you from, Mulehouse?”

- Buddusky’s drunken toast “to Batman, Superman, and the Human Torch” followed by a bray of laughter, and his explanation that “the Human Torch goes like this…throws a ball of flames off on ya and the fucking building goes up…and he had a littler guy that flies around with him.”

- The slightly surreal duplicate representations of Buddusky trying to charm young Nancy Allen with his Navy horseshit at a party: “Doin’ a man’s job. Talkin’…to ships…” as he accidentally hits the lightbulb with his arm and his eyes follow it back and forth.

- The simultaneously horrifying and hilarious sight of Buddusky in his shorts and cap, poking a finger into Meadows’ chest. When Meadows says that he likes Buddusky: “I’m taking you to jay-uhl, motherfucker.”

- Transcribed as best I could: “AAAARRRRRCOMEONMULEGODDAMNITYAWANNAGETTHEGRUNTSDONCHA?!WEGOTTAGOFIGHTTHEGRUNTSWEGOTTAFIGHTTHEGRUNTS!”

Did I mention that this movie revels in being profane? Gloriously, unequivocally profane.

I don’t mean to give Otis Young short shrift here: he is truly wonderful as Mule. As Rear Admiral ZODIAC MOTHERFUCKER (ret.) pointed out, exasperation is the most cinematic of emotions. Over and over, Young is the embodiment of that here. At the final picnic, he is beyond incredulous that Buddusky forgot to buy buns for the hot dogs. When Buddusky looks like he’s going to lose their entire wad playing darts in a bar, Mule simply turns away and mutters, “Fourteen years. Fourteen motherfucking years.” And watch his reaction when the bearded doofus gets in his face about Nixon. Best of all, even when he’s on track to making time with a young lady, he’s unable to suppress his contempt for the come-on platitudes he himself is mouthing:

Girl: “How did you feel about going to Vietnam?”

Mule: “Man says go; gotta do what the Man says. We’re livin’ in this Man’s world, ain’t we?”

Girl: (with utter sincerity) “Oh, wow.”

Mule: (openly dismissive snort)

Towne’s wise decision to alter the ending of the story in one significant way forces us to re-contextualize the title itself. In Daryl Ponicsan’s novel, Buddusky suffers a fatal heart attack shortly after completing his errand. This, it would seem, is the last detail in the novel The Last Detail. It also means that, literally, this has been the character’s last “shit detail”. Without that heart attack, the last detail of the film is Buddusky and Mulhall walking away from Portsmouth and making painful small talk about how they’re going to fritter away what remains of their time off the base (tellingly, they’ve already reached an unspoken agreement to split up, as so many families do after the loss of a child).

“I hate this motherfucking, chickenshit detail,” fumes Mule.

“Maybe our fucking orders will come through,” Buddusky grumbles.

In the days to come, when they think about their time with Meadows, will Buddusky or Mulhall be able to obscure the last detail of this story, even in their own minds? Will the passage of time turn the sour concluding note into the defining element? Will it fundamentally taint the joy of making Meadows an honorary signalman, getting him drunk and laid for the first time, and seeing him punch out a Marine at the bus station? And what of the boy? Will his time in Portsmouth strip away his sensitivity and optimism, or just break him entirely? The martial drums over the end credits suggest that the Navy doesn’t have time for these concerns.

Stray Observations

- In my history of overwritten reviews, this may be the most overwritten of them all. If you’ve made it this far, a silver lining: I’ve omitted my laborious examination of the film as a variation on the story of Abraham and Isaac, modified for the godless universe of 1970s movie brats. You’re welcome.

- I mentioned that this is a road movie, and I stand by that, since the plot primarily consists of getting from one place to another; but don’t look for any beauty in the passing scenery, or anticipate anything like Easy Rider’s lush motorcycle montages to the strains of The Band or The Byrds. Michael Chapman’s unrepentantly grainy photography shows us a countryside that is absolutely dreary, cities that are cold and forbidding. Johnny Mandel’s score is little more than parades and dirges. To put it this way, if the sun-kissed hippie paradise of the open road in Hopper’s film felt dated six months after its release, the frosty image of three landlocked sailors fresh off a bus, noses red with cold, gazing longingly into a restaurant, is timeless.

- One thing I’ve noticed and wondered about is the recurrence of two lines from Five Easy Pieces in The Last Detail: Tita’s opinion that “sailors are sadistic” becomes Buddusky’s observation that “it takes a sadistic temperament to be a Marine”; Bobby calls Elton a “cracker asshole” and Buddusky refers to the racist bartender that way. These may be meaningless coincidences, but I’ll need to be sure where to send the royalty check when I get “I AM THE MOTHERFUCKING SHORE PATROL MOTHERFUCKER” tattooed on my back.