SPOILERS keep fallin’ on your head.

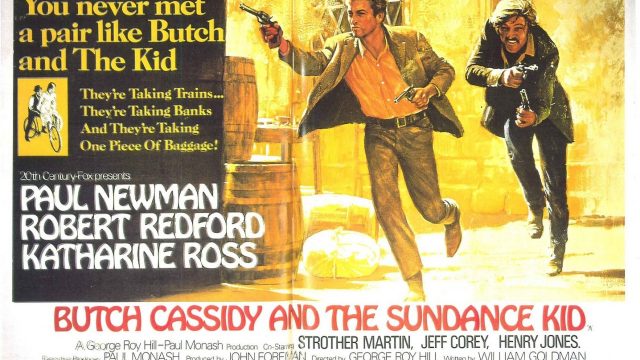

How you respond to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid largely seems to depend on how you feel about hanging out with Paul Newman and Robert Redford. Like all hang-out pictures, this film lives and dies with the charisma of its leads. The movie itself has other things going for it, and more than a couple of strikes against it, but in the final analysis, a viewer’s enjoyment will (and, probably, should) constitute a kind of final reckoning.

This may seem self-evident, but, for that reason, I’ve never really understood the venomous antipathy that a movie like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – which is trying just so hard to be a good time – provokes in certain corners. And yet, my own personal affection for the film notwithstanding, I suspect I’ll spend the next thousand words bitching about it.

Not only is this is a Newman/Redford picture, it’s one scripted by William Goldman, so every moment is staged for maximum chemistry, every line is terribly clever (or building to something clever), and if there’s a story inside somewhere, hey, I guess that’s a good thing too. And a “Most of What Follows is True” story at that.

But is it a western? Does this question even matter?

I’ve always regarded Butch and Sundance a buddy comedy with a melancholy ending (it doesn’t really attempt to earn a label like “tragic”), sporting a few musical montages of varying success, and an extended suspense sequence that works like gangbusters. Our heroes ride horses and wear hats, but aside from that, this has to be one of the least western-feeling westerns of all time.

Lest we forget, this is 1969, and if time ever forced a film to straddle an awkward divide, it’s this one. Indeed, there’s a somewhat surreal quality to watching two of the hippest, most beautiful men in the world play backyard cowboys at a time when the western was on a respirator. That same year, The Wild Bunch came along and blew up the entire genre, and it’s not exactly a secret that the two movies share some of the same DNA (outlaws live too long and go down south to die), though the results are worlds apart. (There’s also the Strother Martin connection – more on that later.)

If there’s an underlying problem here, it’s probably not one of genre, but of tone. Individual scenes play very well, and the sheer brute star power, along with Conrad Hall’s justly lauded cinematography, makes the proceedings go down real easy. But our doomed heroes don’t quite sell their own humanity. They waltz in and out of danger with readymade quips on their lips, ride a bicycle, court Katherine Ross, jump off of a cliff – and it doesn’t cost them a damned thing until the very end. And the film’s considerate enough to spare us even that terrible moment.

Watching it again, what’s most striking is the bigness of Newman’s performance. I’d argue this is the film’s defining characteristic, and it’s hard to decide whether this element is necessary for the movie’s success, or an albatross around its neck.

William Goldman got some of his first work adapting Ross Macdonald with 1966’s Harper, also starring Newman. The contrast between the two projects is startling. Where the role of Butch Cassidy showcases the actor’s charm with rather arch insistence, the earlier film features Newman’s least charismatic work – he’s petty, dour, and exhaustingly cynical from frame one; Butch is grand, optimistic and endearingly naïve – which may account for the relative success of the two projects. (Even a neo-noir junkie like me finds Harper a bloated drag.)

It might be apocryphal, but a story has persisted that Newman and Redford switched roles at the last minute. For the film’s detractors, this probably constitutes proof positive that the film’s “characters” are little more than Hollywood beautiful people whose job it is to act as historical sock puppets, mouth Goldman’s hipper-than-thou dialogue, and mug for the camera. I’ve never had trouble imagining Newman as Sundance (in many ways it’s a part tailor-made for the more taciturn aspects of his 1960s persona, used to great effect in 1967’s Hombre), but Redford as Butch?

Another lingering production tale involves Newman having to redo many of his scenes in a more emphatically comic style. True or not, this absolutely makes sense, particularly when contrasted with just about any other lead performance in any western ever made: Newman seems determined to take his many moments of indignant or enthusiastic verbosity into a decidedly unnatural range, hammering certain words or phrases like his life depends on it.

Among the many “Sell the laughs, Paul” moments:

“You guys can’t want Logan?!”

“Next time I say, ‘Let’s go someplace like Bolivia,’ let’s go someplace like Bolivia!”

“Woodcock?”

And even the cherished, “The fall will probably kill ya!”

Line after line, we feel Newman tugging on that teat for all it’s worth. Maybe that’s why some of the film’s most satisfying moments involve the universe calling Butch to account for his endless bullshit. I’m thinking of Redford barking, “And you, your job is to shut up!” or the stymied silence of the Bandidos Yanquis trying to rob a bank without knowing Spanish. Even more effective is the stark prognosis from wonderful character actor Jeff Corey, which ends with the assertion that the two dreamboats will inevitably “die bloody; all you can do is choose where.” But such moments are the exception, and they sit somewhat uneasily within the film as a whole.

The broadness of Newman’s work gradually seems to affect Redford, who spends a significant portion of the film brooding handsomely, his unflappable gaze (and mustache) doing most of the work, before the snappy rhythms of his costar effectively bludgeon any possible underplaying into submission. This can be seen in microcosm during the sepia-toned sequence that introduces Sundance, a largely single-shot affair that holds on Redford’s glowering face in close-up while we hear Butch affably jawing off-screen. Then Newman physically insinuates himself into the shot of Redford, taking the camera hostage and leading it away.

It’s a nicely staged scene, and director George Roy Hill (The Sting) makes the most of it, but by the time we get our punchline – “I can’t help you, Sundance,” – it’s hard not to feel like it’s we, the audience, who are being played. Of course Redford is the Sundance Kid. We saw it on the poster – hell, we can see it in his eyes – and it’s well understood that he can quick-draw anyone’s sorry ass, especially this off-screen voice accusing him of cheating.

Here and elsewhere, Goldman is being too damned cute to sustain the drama; real danger is often conspicuous in its absence. This is probably why the best part of the film involves the pair riding like hell to get away from a posse of top-flight hired guns. The latter’s gradual progress in doggedly pursuing them is observed from afar – D.P. Hall earning his pay, and his Oscar, with some lovely work – and without musical accompaniment. It’s a wonderful sequence, and worth celebrating, but it’s over too soon, and it almost feels like a fugitive from another film.

Speaking of fugitives, Katherine Ross acquits herself just fine in a part that feels more thankless with each passing year. Not only does she get a rather creepy introduction by way of a gun-point striptease (that turns out to be something like foreplay, so we can safely laugh at it – ha, ha, ha), she then has to serve as den mother and love interest for our two adolescent cowboys. She smiles through a series of montages, goes to Bolivia with them, teaches them a few useful Spanish phrases, then fucks off so that she doesn’t have to watch them die. (To be fair, the audience itself could be co-indicted on some of these counts.) Who said there were no good parts for women in 1969?

And then of course there’s Bolivia.

Remember how The Wild Bunch spends much of that film in Mexico? How the country and her people become characters in their own right? How the depravity of Mapache and the idealism of Angel do battle for the souls of the gang? How the sadness of the entire nation seems to infect our antiheroes, building to the most cathartic and cataclysmic violence the screen has ever known?

Well, there’s nothing like that in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. If the film’s to be trusted, Bolivia is a place where heroes go to rob peasants, bitch about the peasants not having enough money, and meet up with the eccentric (or, as he puts it moments before being shot, “colorful”) Strother Martin. Martin, who becomes a serious contender for MVP status with a scant five minutes of screen time, elevates the whole enterprise (“Morons. I’ve got morons on my team.”) but he’s also a walking, talking reminder of that other 1969 western.

Yet another reminder is the rather overwrought slow-motion outburst of violence that follows a confrontation with some homegrown bandits, who mistake Butch’s pleading “por favor” as an invitation to throw down. The moment itself isn’t poorly executed, but once again Butch Cassidy can’t resist an opportunity to turn a deadly situation into a highly improbable verbal gag, confessing to his partner that he’s never had to shoot anyone before.

“One helluva time to tell me,” observes the expressionless Sundance.

I don’t know if this revelation falls under the “Most of What Follows” designation, and I don’t care; this film’s representation of Butch and Sundance, with their easy back-and-forth and complete loyalty to one another, in concert with their profession, makes the moment ring completely false. I suppose we could rationalize that Butch is such a fast-talking snake oil salesman that he’s never needed to kill a man, but that feels like reaching.

(See? I knew I’d spend the bulk of this piece throwing shade at a movie I like.)

The film famously ends on a sepia freeze frame – Butch and Sundance’s last moment on Earth – but has the film earned the right to shoot for such a downbeat sendoff? Is a commitment to “sorta truth” enough to justify an ending like this?

As a kid, I thought it was one of the saddest things I’d ever seen, but in hindsight, it was probably only the sadness of seemingly invincible figures being blindsided by their own destiny – all that “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” optimism for naught. Cop-out or not, it’s hard not to admire the final shot – a zoom-out on a simulated ancient photograph, two outlaw superstars frozen forever in their final, desperate moment.

Maybe the film is just too agreeable. It makes you suspicious. In the midst of laughing at certain lines, it’s hard to ignore that such amusement is actively undercutting any reality the story might have. Director Hill associated with his share of lovable rogues in life (J. P. Donleavy and Gainor Stephen Crist among them – respectively, author of and model for The Ginger Man), and if I’m wagging a stick at him for keeping the proceedings too light to foster tension, I’ve got to admit that I’ve never heard anyone call the movie “boring.” So maybe these aren’t significant aesthetic criticisms so much as personal quibbles.

And hey, maybe its attempts to be ingratiating only fall particularly flat if you’ve just watched The Wild Bunch. Or if you loathe distractingly anachronistic musical montages. Or if you prefer overtly genre pictures to toe the line, as it were. For her part, Pauline Kael singled out the obvious studio looping for ridicule. I get the sense that David Thomson never really cared for Newman or Redford, so of course he’s particularly ornery about the movie. Roger Ebert gave it two-and-a-half stars out of four, but the review itself reads like a laundry list of grievances.

If my own complaints about the film sound petty in a “can’t see the forest for the trees” way, I have to explicitly reiterate something: I always enjoy watching Butch and Sundance; I’ve easily seen it a dozen times, with no regrets. The problem is, when the final volley has been fired and the credits have rolled, I’m haunted by the sense that I’ve been duped, that the problems afflicting the film could only be glossed over by a zealous apologist, one blinded by nostalgia, or vainly seeking approval in Newman’s thousand-watt blue eyes.

“Boy, you’re a romantic bastard – I’ll give you that!”