Its hard not to compare Star Wars and Dune when reading the latter decades after their respective releases, as Lucas obviously knicked and filtered some of Frank Herbert’s ideas and storytelling through his own process. Wars has also completely permeated popular culture while Dune remains on the edges, an object that is just as grand and ambitious but is nowhere near as easy. Each shares similar goals, depicting alternate universes where mysticism and harder political realities tensely co-exist. Lucas and Herbert both recall Drunk Napoleon’s notion of artists creating good, pulpy work by throwing everything they think is cool or interesting into the mix. Lucas combines drag racing, Eastern philosophy Campbell, and Flash Gordon. Herbert uses ecology, drugs, Arabic culture, Messiahs, and geopolitics to tell his story.

But Lucas, for all the epic and religious elements of Star Wars, preferred to keep his protagonists quippy and flawed, bantering amid all the wonder of the galaxy. There’s no room in Dune for a scene like Luke and his friends bursting out in laughter and relief once the compactor stops.

Nothing in the tone of Dune has much room for wiseassery. What Herbert chose to focus on in tone and scale is graver and immersed in religious awe, and every critical juncture for the Hero is another moment in Paul’s journey towards the constant terror of tremendous Godhood – and the cost required to accomplish this destiny. Beloved commentator Miller wrote about Streets Of Fire that the text, instead of riffing on its own world-building or directly commenting on the tropes, treats the mythology with deadly sincerity. The characters here similarly have no distance from Spice or Paul Mua’dib or the falls of the houses – they are living completely in this narrative space.

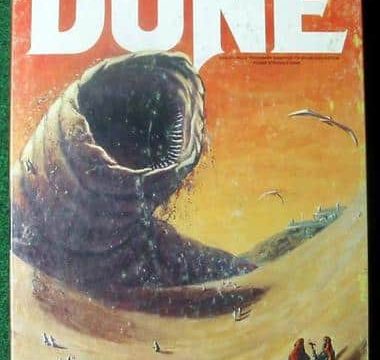

A friend of mine gave me his copy of Dune and asked me to read it. The cover was rather mysterious and beautiful – shadowed figures lost amid the vast desert terrain, blue sky drowned out by enormous pillars. I knew the reputation and promised him that I’d read it. A few months later, battling the depression that loomed over his whole life, he would kill himself. I kept the dog-eared book on my shelf, vowing for years to plow through it someday, even if the thing did require a glossary. I finally immersed myself in the book after turning twenty-six.

I was soon struck by the earnestness of the thing, as well as how colossally real the myth of Paul felt, tinged with the glorious purpose of all epic stories, yet how adult the entire story is too. Paul’s Messianic status will lead directly to genocide, death, and war, and the real journey Paul takes is towards completely accepting his fate and everything that involves. I wondered if my friend felt a similar relentless pressure, if he understood something about the inescapability of things and the burden Paul carried, but its impossible to ask him that now.

I do know that the older I get the more I understand that kind of Recognition, that mythic acceptance of oneself and the evil we often commit, while Luke’s mostly uncomplicated heroism fades, year by year, into the places where childhood things go to stay. Dune, absurd as it is, has stuck with me, a story where great burdens and mystic transformation inhabit the same uneasy, endless spaces.