“That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.” – Michael Corleone, The Godfather

“Your country ain’t your blood, remember that.” – Santino Corleone, The Godfather: Part II

These two quotes effectively summarize the central conflicts in the first and second volumes of The Godfather. The first film is about the choice Michael must make between being true to himself and being true to his family. The second is more expansive, going backwards and forwards in time to show how this family came to be, and what the consequences have been for its descendants and adopted country.

In other words, this is a story of immigrants: how they came to America, how America molded them, how they, eventually, begin to mold it.

Director Francis Ford Coppola, of course, was aware of the Corleones’ outsider status in American society from the first film. Michael’s conflict in that film, between assimilation into American society and loyalty to his family, sensationalizes a familiar dilemma for many second-generation immigrants. The tension between being “a good American” (in the words of the undertaker whose speech opens the movie) and a member of “the family” runs through the whole film. But the movie’s scope is limited to the book’s singular focus on the Corleone clan.

With the sequel, Coppola was free to expand his vision, in time as well as space. The original’s scenes of hard men forging dubious allegiances in dark, hermetic rooms are complemented with scenes of the family out in public, vacationing in Havana, glad-handing politicians, and being called before congressional investigations. And in the parallel story of young Vito Corleone’s rise, we see him navigate the Italian immigrant neighborhoods of 1910s New York, not as a cloistered mafia don, but as a family man just trying to get by. The effect of these choices is to pull the Corleones into the world around them, and let the audience see how they fit—or don’t.

The film opens in Sicily at the beginning of the twentieth century. The terrain looks dry and barren, and the first people we see are pulling a coffin over it. The coffin holds the father of young Vito Andolini, whose life moves from bad to worse with absurd rapidity. His father is dead and his brother has fled for the hills as the movie opens. His brother dies in the funeral procession. His mother takes him to the local mafia don to beg for his life, he refuses to listen, and she pulls a knife on the don, sacrificing herself to let her son escape.

Vito’s arrival on Ellis Island initially comes as a relief from the madness and violence of Sicily. That place held no future for Vito; this new country, with its statue welcoming “the wretched refuse” of the world to its shores, seems to hold out some hope — but here, too, the obstacles seem nearly as foreboding. Vito is lost in the teeming masses, shunted into endless lines, his name changed to “Corleone” by a clerical error. A smallpox diagnosis from an overworked doctor sends him into quarantine. In a small room, he gazes at Lady Liberty again, this time from the window of his cell.

This opening, already audacious in its willingness to spend the first ten minutes of screentime with actors the audience doesn’t know, sets up the dichotomy for the rest of the film: the Sicilian way of life, with its endless vendettas and death, holds no future, nothing but death. America may hold something different… but is it in reach, or will it always remain on the other side of the glass?

Back in the present, the Corleone family seems to have gotten over to the other side: all three of the surviving Corleones have non-Italian spouses, and the first communion celebration that Michael hosts for his oldest son is a loud, public affair: a senator drops by, and it’s difficult to tell if the men in the parking lot with cameras are FBI agents or society reporters.

But behind closed doors, the façade drops. “I don’t like your kind of people,” snarls the senator. “I don’t like to see you come out to this clean country in your oily hair, dressed up in those silk suits, and try to pass yourselves off as decent Americans.” Fredo’s wife, drunk and angry, yells “Never marry a wop! They treat their wives like shit! I didn’t mean to say ‘wop!’”

Though it feels like a relic of the past today, the discrimination faced by Italian immigrants to the United in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was formidable. Sicilians, especially, were considered suspect, their darker skin and proximity to Africa leading many to claim that they weren’t “real” whites. In the present day, where the image of a lone child refugee locked away in quarantine feels painfully relevant, it’s easier than ever to see the Corleones as a family of immigrants, caught between trying to assimilate into the world around them — to “become legitimate”— and retreating into comforting Old World family structures that further cut them off.

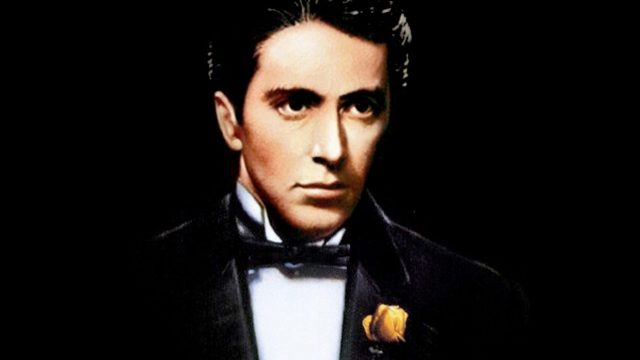

It’s Michael, in particular, who attempts to bridge these gaps. Before the events of the first movie, he appears to function as a “model minority,” fighting for the United States (and, though he fights in the Pacific theater, nominally against his father’s country) in World War II, going to college, and marrying Kay, by all accounts willing to assimilate and become a good American. In allowing himself to be dragged into the family business, he throws all that away.

In the sequel, he’s putting on the appearance of that person, but no one buys it. Kay notices that he seems in no hurry to “go legitimate,” and at a congressional inquiry, after reading a statement in his defense, the chairperson dryly responds, “I’m sure we’re all quite impressed. Particularly with your love for our country.” He has been relegated to outsider status, at least in polite society.

I must have watched The Godfather Part II half a dozen times, and I’m still not sure I could explain the patchwork of conspiracies and double-crosses that comprises Michael’s plot. I am sure I have no idea who ordered the hit on Michael through his bedroom window. But when I see the story as a second-generation immigrant trying to choose between tribalism and assimilation, this confusion becomes an asset rather than a liability. After all, Michael doesn’t know who ordered the hit either.

So while his situation would seem complicated, and seems even more so by the sequence of hits and double-crosses he may or may not order, it really comes down to a choice: the worldly, thoroughly Americanized Hyman Roth, offering possibilities of further expansion and enrichment on one hand, the old Italian family, with its promises of tradition and stability, on the other. With whom does he wish to ally himself? And what happens if he chooses wrong?

When he first learns of the existence of Black Hand agent Don Fanucci, Vito asks his friend, “If he’s Italian, why does he bother other Italians?”

The friend responds, “He knows they have nobody to protect them.”

It’s this, the immigrant minority’s need for “protection” and their inability to get it from the police, that causes Vito to turn to crime. Don Fanucci’s racket has already put him out of a job…why shouldn’t he try to take Don Fanucci’s, and possibly provide some real protection for the people in his community? If his “business” weren’t extortion, robbery, and murder, he would be seen as an exemplar of market disruption.

Roger Ebert infamously disliked the sequences with young Vito, interpreting them as a counterpoint to Michael’s storyline: “We’re left with the unsettling impression that Coppola thinks things would have turned out all right for Michael if he’d had the old man’s touch.” Vito’s story is a counterpoint to Michael’s, but I think Ebert makes a mistake by attributing it to the behavior of the two characters: it’s more a referendum on systemic issues than on the people involved.

Vito’s success comes from a good idea at the right place in the right time. His story is simpler because his world is simpler; he is not besieged by federal police or old resentments. After killing Don Fanucci, the yellows of Sicily recede from the cinematography of Don Vito’s scenes, replaced by a cold blue tint. He has broken with his past, is in a new country, and has started an up-and-coming criminal enterprise with Prohibition only four years away. When he settles his own family debts, it is a luxury, a final superfluous break with a past he had left behind long before.

Does Michael have this choice? It’s difficult to say, because he never really tries to make it. He is drawn further and further into the world his father created.

The final shot-reverse-shot between him and Kay confirms this. She is standing in the doorway, backlit by clean blue light, the woman he was set to marry as a college graduate with a Navy Cross and a family that was his family, but wasn’t him. He is in the house, bathed in the sort of light that viewers today still associate with the Godfather films: the yellowed hue of close shadowy rooms and Sicilian dust.

He closes the door on her, of course.

Tragedies are often marked by protagonists who are unable to adapt to changes in the world around them, and are brought down by people who better suit the times in which they live. Rare is the tragedy that suggests its protagonist, at some point, had the chance to adapt, and refused. In The Godfather: Part II, we see the moment where a boy, shut in a small room, takes his first steps into a new world that seems to offer endless possibility. And we see the moment where another man, having been brought up in this world of possibility, closes himself back into his room. With his family.