You owe it to all of us to get on with what you’re good at.

– W. H. Auden

We loved killing time and had perfected several ways of doing so. We wandered the hallways carrying papers that indicated some mission of business when in reality we were in search of free candy.

– Joshua Ferris, Then We Came to the End

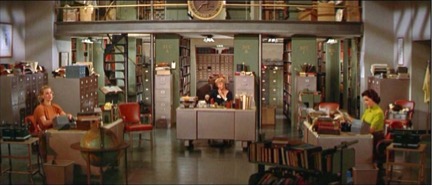

What I come back to in Walter Lang’s Desk Set is its fantasy workplace. The chemistry between Hepburn and Tracy is predictably excellent, the low-key crackle of like minds recognizing each other, but the real love story here is between Bunny Watson’s team and the Federal Broadcasting Network reference library where they work. It’s not a question of vocation—no one here is Hildy Johnson, newspaperman—but of enjoyment and the bittersweet suspicion that they would never enjoy themselves as well anywhere else.

When it comes to the human relationships, Desk Set is realistic, and sometimes surprisingly frank. When it comes to the job, it gets starry-eyed. That makes it the forerunner not so much of the job-as-plot-device run of rom-coms like How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days—thank God—but of the more optimistic workplace comedy, where coworkers become family and everyone really believes in, say, putting on a Harvest Festival, and the goal is for nothing to ever really change.

Romance at its best, whatever its players are, combines adventure with security; utopias are much, much better at the latter than the former. Trying to do both pulls Desk Set just a little bit off-balance, but in ways that are more interesting than damaging.

Like most utopian stories, Desk Set starts with a stranger being introduced to paradise.

The stranger is Richard Sumner (Spencer Tracey), an efficiency expert and methods engineer who also apparently singlehandedly designs complex computers while personally conducting site visits to oversee their installation and customization, suggesting that efficiency may not actually be his strong suit. He’s firmly out of the Eccentric Genius mold, wearing mismatched socks and forgetting the day of the week. He is, as the network president’s secretary puts it, “a character… some kind of nut, I think. Or somebody very important. Probably both.”

Sumner has a unifying sense of humor and warmth, but the movie ultimately has to use him as a feint. In order to have any conflict at all, Bunny Watson (Katherine Hepburn) has to think it’s possible that he might really destroy her utopia, and Sumner, well into a warm and realistic flirtation with her, would completely misread the social cues of a once-friendly office gone arctic-level frosty. It doesn’t quite work, partly because the original play was bent slightly out of shape to insert the joy of Hepburn/Tracy. Screenwriters Phoebe and Henry Ephron did an admirable job welding the distractible, ultimately benevolent engineer to the distractible, wry romantic lead, but the seams show around the plot.

Sumner has come, we learn eventually, to oversee the installation of his machine EMERAC: an “electronic brain” that will dominate the floor space of the library and, everyone worries, the work of it as well. (EMERAC, or Emmy, is glorious in a fifties tech kind of way, like a Lite-Brite crossed with Ask Jeeves.)

Sumner’s familiarity with his machine’s virtues and limitations means he considers it self-evident that Emmy will do only the rote grunt-work of the reference department, pulling hard-to-find statistics and making rapid calculations; Bunny is less convinced. And, really, she should be. The flimsy reason for Sumner’s secrecy is that he was asked to conceal a coming network merger to keep stock prices down, but the relevance of EMERAC to the merger is that, effectively, without the merger, EMERAC would mean lay-offs.

Sumner’s familiarity with his machine’s virtues and limitations means he considers it self-evident that Emmy will do only the rote grunt-work of the reference department, pulling hard-to-find statistics and making rapid calculations; Bunny is less convinced. And, really, she should be. The flimsy reason for Sumner’s secrecy is that he was asked to conceal a coming network merger to keep stock prices down, but the relevance of EMERAC to the merger is that, effectively, without the merger, EMERAC would mean lay-offs.

But, because this is a fantasy, Desk Set peels back from that at the last moment, as the EMERAC machine in the payroll department flubs and sends out pink slips to everyone in the network, proving that humanity can’t be entirely replaced. (Open the library doors, HAL.) A more plausible mistake, and one that still resonates, is the way EMERAC can’t distinguish fake information from real: it’s just fifties Google, turning up results based on popularity.

It’s that combination of reality and cheat that makes Desk Set both lasting and too flawed to be a masterpiece. What it is instead is a remarkably appealing confection, sweet but not too sweet, always with just enough bitterness or saltiness to make it interesting.

Part of that realism comes simply from the casting of Hepburn and Tracy, who are far older than romantic comedy characters are generally permitted to be, and who are allowed to look it. Hepburn is gorgeous, but her face is visibly lined, and the high collars she wears to hide her neck are as much Bunny Watson’s carefulness and pride as her own. Tracy is also lined, and his hair is completely white. That Bunny has spent seven years in a dead-end relationship is evoked frequently, in frustration and pain: if she clings to the caddish-but-not-too-caddish Mike Cutler, her boss, it’s partly because she doesn’t feel she can start over.

“You’re like an old coat that’s hanging in his closet,” Joan Costello’s Peg tells her. “Every time he reaches in, there you are. Don’t be there once.” Bunny says, “He’d just buy himself a new coat,” and it’s an estimation of herself that it’s painful to see. “What makes you think he won’t anyway?” Peg asks. Bunny considers it, and falters: “Well, if he did, it… that would be awful, wouldn’t it?”

You go along thinking tomorrow something wonderful’s gonna happen. You’re not gonna be alone anymore. And then one day you realize it’s all over. You’re out of circulation. It happened, and you didn’t even know when it happened.

Sumner has less loneliness, but only because he’s less compromising; he hasn’t had any better luck in finding suitable companions. (His account of his fiancée, whose letters to him during the war were lengthy explanations of fashion trends, is one of the more priceless parts of the movie. Explaining how he orchestrated her jilting of him for his friend, Sumner defends himself from the charge that it was a “dirty trick”: “What are you talking about? They’re very happily married. If she never writes him a letter, he’ll never know the difference.”)

They’re both starved for a meeting of the minds—and for some sexiness, which is simmering but present. When Bunny and Sumner are caught in a rainstorm, he waits the rest of it out at her apartment, dressed in the monogrammed dressing gown she bought for Mike Cutler—a Christmas present for a disinterested, absent lover turned into a kind of appropriated intimacy with another. And Sumner’s delight in Mike discovering and mistaking the situation is obvious. Spencer Tracy wears the living hell out of that robe, with the full confidence of a man who knows he has the better claim to it, initials or no. And when their flirtation, with the thrill and informality of the network’s Christmas celebration and with Bunny’s tipsiness, turns more obvious, as they sit in the stacks and talk, there’s an almost teenaged feeling to them, a rediscovered youth.

In the grand tradition of romantic comedies, both their sex appeal and their suitability is conveyed through banter and wit. Bunny first attracts Sumner’s attention when, over a lunch of vending machine sandwiches eaten on the building’s roof in December—“No, no, don’t worry,” he says, oblivious, “I never get cold”—she aces his set of confounding memory tests and logical puzzles.

In the grand tradition of romantic comedies, both their sex appeal and their suitability is conveyed through banter and wit. Bunny first attracts Sumner’s attention when, over a lunch of vending machine sandwiches eaten on the building’s roof in December—“No, no, don’t worry,” he says, oblivious, “I never get cold”—she aces his set of confounding memory tests and logical puzzles.

“I’m in the habit of associating many things with many things,” Bunny says, to explain her uncanny ability to form mnemonics on the fly: “Aren’t you going to ask me how many people got off the train at White Plains? Three… You see, I’ve only ever been to White Plains three times in my whole life.” “Well, supposing you’d only been there twice.” “But I wasn’t. I was there three times.”

At this point, she’s showing off, adding questions he never even thought of asking: she’s sparkling with the pleasure of it, and it’s no wonder he falls in love with her.

They come together over intelligence but also, pivotally, over work, which brings us back to the fantasy of it.

One of the signs that Mike Cutler is unsuitable is, surely, that he cares about his job only as a career, as a series of advances: he cares about his job but not about his work. Indeed, when Sumner asks after the Reference Department, he’s told Cutler’s in charge. “Well, [Bunny Watson] runs it, but he’s her boss.” Sumner, a smart man: “Let’s not bother with him.”

So they both love what they do and appreciate other people loving it too, but the fantasy extends beyond that. It’s in the warmth of the reference library—the color palette is believable but bright and warm, and the layout is well-balanced; it’s one of the places where the movie owes a special debt to the play, to the theatrical significance of staging—and the easy camaraderie of the people working there, from the way Bunny and Peg rub along, boss and subordinate made into equals by long friendship to the way Bunny offers advice and advancement to her youngest employees.

A good job, Desk Set suggests, is one where you have entertaining work—enough to keep you busy, but not enough to completely fill up the day. You need time to gossip—catty, unconvincingly married Bradley Smithers seems to perpetually be by the water cooler, waiting to pass on information, sometimes helpfully, sometimes with that crucial oh-I-hate-to-be-the-one-to-tell-you vibe of schadenfreude, and so much flows through the office grapevine of secretaries and assistants that trying to keep information out of it becomes a plot point. You need the leisure of boozy Christmas parties where callers are given inaccurate information about reindeer. You need the little creature comfort of an office philodendron. You need the freedom to smoke—one of the most ominous signs of EMERAC’s possible tyranny is that its machinery is too delicate for the librarians to smoke indoors, which is given even more emphasis than its stringent and uncongenial temperature requirements. For the most part, that fantasy has aged well. It’s remained true to human desire, if not to human reality, but it’s melded with just enough reality—the threat of lay-offs—to give it a veneer of plausibility.

And, now, to give it a veneer of melancholy. Because Desk Set is a fable—a reassuring balm applied to fifties technophobia, a story of the time people thought computers were coming for their jobs but really they were just coming to make their jobs even better—and now the truth of its happy ending seems, if not unbelievable, than temporary. You don’t need a human connection anymore to find the words to “The Night Before Christmas.” And you probably can’t smoke indoors.

But none of that can change the humor of Sumner proposing to Bunny through EMERAC and EMERAC saying she shouldn’t marry him—“Well, I told you myself that EMERAC could make a mistake.” If it’s impossible for me to entirely believe in the misfires—or at least the longevity of the misfires—of the weapons that would be turned on the work utopia, Desk Set shows me that I want to believe in them. Utopias are a good way of exploring what we value and, in the limits of their plausibility, exploring what we understand.