The cultural shorthand for early-70s American filmmaking is that directors had a significant degree of leverage over the studios. Except, when they didn’t. Case in point: not until Two-Lane Blacktop was released on DVD (in a proper aspect ratio, even) in the late 90s could you see the (in)famous ending, where the film seems to burn up in the projector. As Kent Jones points out, the Universal studio projectionist (concerned about the potential damage to the reputation of projectionists everywhere) was strongly in favor of the decision made by the suits to cut the final image from the studio print.

Monte Hellman, the director, said that the ending was inspired by a similar moment of cinematic combustion in Persona (1966), written and directed by Ingmar Bergman. By the time Hellman completed the editing of Two-Lane Blacktop, what started out as a prototypical American road movie about two guys in a hot rod had a dissipative undertow that felt more related to European cinema. Even if Two-Lane Blacktop had fewer psychological flashpoints than Persona, both films framed the recurrence of communication breakdowns and fragmented identities in wide-screen compositions.

In Two-Lane Blacktop, the two leads, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, were non-actors known far more for their musical cred: Taylor was a burgeoning 70s-singer-songwriter superstar, while Wilson was the drummer for the Beach Boys. In the film, they hardly speak. Conversely, Warren Oates, building his reputation as an actor’s actor, plays a middle-aged hot-rodder, who meets up with Taylor and Wilson on the road, and has an obsessive need to fill in the silences by telling invented stories about himself.

There’s a girl, too, played by non-actor Laurie Bird, known, in the film, as the Girl, just as Taylor is the Driver and Wilson is the Mechanic. Oates is GTO (as he drives a Pontiac GTO). The characters’ names all denote a sense of, at best, limited possibilities. Oates’s forceful delivery of GTO’s increasingly convoluted and desperate monologues convey the impression of America as a dream of open roads receding in the rear-view mirror.

Given the film’s evanescent plot (loosely based on a street-level view of hot-rod culture), we are compelled to pay attention to these characters, even when how they come across doesn’t exactly reward our interest. The Driver is a hardcore asshole who retreats from the spotlight as much as he can. The Mechanic is goofy and pedestrian, probably ending up, as Charles Taylor remarks, “at forty, in some crummy garage, maybe tooling around with a sports car on the weekend.”

GTO is more sympathetic. In a later scene—which, in a more mainstream film, might promise a better chance for redemption—he tells the Girl (all three men take turns chasing her) that his time is running out and he needs to find some sort of permanence, “Cause if I’m not grounded pretty soon . . . I’m gonna go into orbit.”

That feeling hits home to most, and was shared by Joni Mitchell, who in the same year as the release of Two-Lane Blacktop, released a masterpiece, Blue, about the ups and downs of a rootless life. The album starts with, “I am on a lonely road, and I am traveling, traveling, traveling,” and in the poignantly regretful “This Flight Tonight,” she is high above the world, momentarily free from all concerns, including James Taylor, back at the film shoot, whom Mitchell was seeing. But, even while drinking champagne and listening to music in her headphones at full blast, she can’t forget him.

Perhaps also forgotten is that projectionists may have played more of a role in 1971 than is usually acknowledged. Peter Biskind reports, in his print-the-legend chronicle of New Hollywood, that after The Last Movie, directed by Dennis Hopper, was screened for the suits at Universal, their stunned silence was broken by the projectionist’s remark, made in the adjoining room, “They sure named the movie right, because this is gonna be the last movie this guy ever makes.”

Tellingly, Biskind, while regaling us with his insider knowledge, provides very little of an impression of what the film actually looked like. As a fairly accurate barometer of its artistic sensibility, The Last Movie won the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival (which Biskind does mention), but it turned off American critics, killing its audience draw, and the studio buried it. The Last Movie has gone down in history as a film maudit (a cursed film) and a Career Killer.

Finally made widely available by a DVD release in 2018, The Last Movie, however you look at it, proves to be visually stunning, like color-saturated postcards arranged with a painterly eye, thanks to Hopper and cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs. But the visual beauty is a set-up, because Hopper’s truly deconstructionist Western is full of mind-fuckery. Hopper places the end at the beginning, thus disrupting the continuity that popular hero/outlaw cowboy pictures rely upon, and then provides misleading explanations for these narrative gaps by inserting “scene missing” cards.

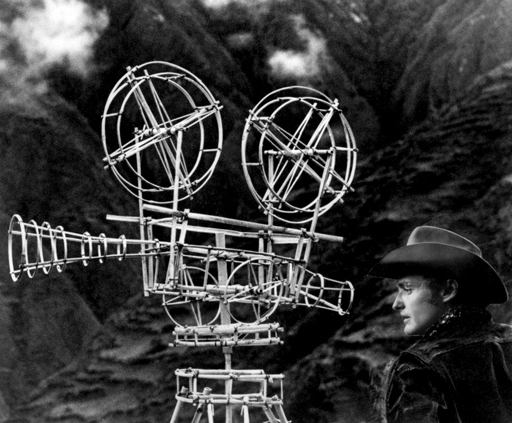

Whereas Two-Lane Blacktop uses silences to show how life on the American home front was spiraling into alienation, The Last Movie’s pissing on the legacy of John Wayne denounced American global imperialism. Hopper plays a stuntman, who stays behind after a Western about the death of Billy the Kid finished shooting in Peru. While he pursues a few money-making schemes, he is recruited to play the leading role in an imaginary film the locals have created, using cameras made out of straw and staging violent scenes that look terrifyingly real, to envision the death of Billy the Kid as a passion play.

Whereas Two-Lane Blacktop uses silences to show how life on the American home front was spiraling into alienation, The Last Movie’s pissing on the legacy of John Wayne denounced American global imperialism. Hopper plays a stuntman, who stays behind after a Western about the death of Billy the Kid finished shooting in Peru. While he pursues a few money-making schemes, he is recruited to play the leading role in an imaginary film the locals have created, using cameras made out of straw and staging violent scenes that look terrifyingly real, to envision the death of Billy the Kid as a passion play.

Hopper is a skilled actor able to disclose the tarnished psychological complexity of the Ugly American. Not only does he behave badly (not a far stretch from the insane life Hopper was leading at the time, fueled by full-blown egomania after the massive success of his previous film, Easy Rider); his existential panic in believing he will actually be sacrificed as the finale of the locals’ “last movie” is a sarcastic take, as Nick Heffernan observes*, on American fears of “savage retribution” for their exploitation of overseas territories.

Considered together, Two-Lane Blacktop and The Last Movie use cinematic images of deconstruction to portend a spiritual reckoning for the American dream. Charles Taylor calls the ending of Two-Lane Blacktop, the film immolating in the middle of a close-up of the Driver, a “beautiful and awful benediction Hellman lays on his movie and his characters.” In The Last Movie, the final words are of the village priest, who says, “Blood is everywhere.” You can ask, “Apocalypse When?”–but it depended, in 1971, on where you were looking.

*There’s no available link for this reference: Nick Heffernan, “The Last Movie and the Critique of Imperialism,” Film International 4, no. 3 (2006)