This article contains spoilers for The Wicker Man.

The staying power of a cult favorite like The Wicker Man lies mainly in its ingenuity and solid execution. The massively influential film’s trope-twisting, genre-bending concepts are nearly as fresh as they were over forty years ago. As a story that comes down to many ideological clashes rooted in the concept of sacrifice, the movie is also undeniably a product of the hypnagogic era of the early seventies – but grounded in an organic sense. Ranked as one of the top horror films of all time by various publications and heralded as the Citizen Kane of horror, what exactly is it that keeps modern-day critics and fans enthralled?

The film experienced a less than favorable critical reception at release. Both concept and production were rushed attempts at a new form of storytelling. Following a moment of hardship in the British film industry, the film’s production studio, British Lion Films, was facing financial turmoil and upset. A condensed filming time meant shooting spring scenes in the autumn by gluing flower buds to trees. It also meant budgets were so tight many involved were reportedly not paid for their contributions. One of those number was Christopher Lee, who played the eerily charismatic Lord Summerisle. Lee went on to call this the greatest movie he had ever starred in, though he always referenced the never released 102-minute version of the film. This original version had been sought after by both Lee and the film’s director Robin Hardy for decades, but little hope has remained for its recovery following the deaths of both men. The theatrical release, despite executive wing-clipping and a horribly bumpy production road, eventually landed in revered cult film territory.

British television actor Edward Woodward was cast as the movie’s main character, Sergeant Neil Howie who investigates the disappearance of a girl named Rowan after receiving a personalized letter regarding the incident. He arrives at the secluded island of Summerisle. This agrarian island is inhabited by Pagans and governed by Lord Summerisle. As a Calvinist, Howie is immediately at odds with the bawdy lifestyles and rituals of the villagers. He also seems to lack the appropriate language to get any of them to open up to him. At first, villagers deny Rowan’s very existence. The unsettling detective work leads Howie to find incontrovertible proof of her existence, but by now the villagers insist on referring to her in very ambiguous, strange language. There are plenty of secretive meanings behind the conversations, but his brash method of charging into situations, flinging accusation and condemnation alike, offers little help in way of uncovering the information he seeks. Instead, he is masterfully manipulated by each villager and ultimately Lord Summerisle himself, leading to Howie’s death in the final scene of the film.

Sergeant Howie does not exude likability, but it’s hard for a first time viewer not to feel some kinship to his cause, if not his personality. He is trying to save a little girl, and he is alone in a land that seems enchanting, but which slowly unravels a sinister darkness. The film is filled with great contrasts even beyond the primary clash of the prude, stiff nature of Christianity and the fluid, sensual stirrings of Paganism. There is a sense of horrified wonder in each unfamiliar sight the Sergeant witnesses. The film masterfully evokes this through numerous vivid musical scenes depicting Pagan rites. Most striking of all is the way the film exposes some of its most insidious scenes in broad daylight, with the merry tunes and broad smiles of the villagers juxtaposing the seeming viciousness of their rituals. Both the bright, saturated colors and psychedelic folk nature of the music lend a surreal sense of disbelief as the simple villagers gleefully perform ceremonies that are fearful and loathsome to Christianity.

Beyond the taunting nature of paranoia which fills the film, there are things we gradually discover about the Sergeant himself that begin to explain his reason for being on the island. He is so staunchly religious, he is engaged to be married and has still never bedded a woman. The openly sexual appetites of the villagers are wildly upsetting to him, and each time their sexuality confronts him, he seems to dig in deeper with his sense of moral rigidity. One of the most alluringly strange scenes of the whole film is when the innkeeper’s daughter, Willow, (played by Britt Ekland), performs a potentially magical musical number. She sings a haunting folk tune with suggestive themes, twirling her nude body around her bedroom and bashing her fists against the walls in tune with her primitive dance. On the other side of the wall in his own room, Howie finds himself drawn to the sounds. He presses himself against the wall, clearly struggling to contain his lust, though he ultimately prevails and returns to bed. Commonly interpreted as a test by the Pagans, this scene also offers a way that Howie may escape the nightmare that still lies before him. His status as a virgin, among other things he represents, is necessary for him to be a worthy sacrifice.

While a virgin sacrifice is a common trope in itself, the movie still finds a novel take. Howie discovers enough to learn that the crops from the previous year were a failure, and that the Pagans seek to rectify this through human sacrifice. He believes that the villagers will choose the missing girl he is seeking. This epiphany of his own victimhood at the conclusion of the film is shocking in that it flips the normal perception that young virgin girls are the most powerless form of sacrifice. When Rowan sees Howie, she springs a trap and pretends to be afraid of the Pagans. She leads the Sergeant to what will soon be the place of his death. With a delighted innocence, she runs to the other villagers and asks if she has performed her duty well. It’s a revelation as relieving as it is unnerving. Now the audience is finally aware of Howie’s status as a pawn every step of the way. His religious offense and standoffish nature regarding the sexual practices of the natives further proves his suitability as the ultimate martyr in this horror. This reverses the age-old construct of sexual promiscuity as a sin that should be punished by brutal slayings, as witnessed in countless slasher flicks.

The buildup to this discovery is the boiling point of the sporadic Pagan sensibilities that have been background noise for the rest of the film. There is a foreboding intent behind the animal masks that begin springing up on the villagers the day of their May Day celebration. Hiding their expressions and their ambition, they join together in a procession of hooting and merriment. There is still a pervasive sense of debauchery despite the bulky, elaborate costumes and hidden identities, which allows Howie to sneak into the festivities and remain, as he believes, unnoticed. The entire celebration is the culmination of the sprouting tension between the joyous naivete and sage cruelty of the ancient religion. This helps illustrate one other core aspect of the film – the importance of the island’s settlement. Lord Summerisle impudently informs Sergeant Howie that his grandfather, in keeping with the Victorian times, settled the island and brought a specially engineered form of fruit that would thrive there. He also convinced the islanders to embrace the Paganistic beliefs of the Old World. This establishes the religion as an instrument of control, as well as the modified produce which the villagers will come to rely upon for their daily lives. There is also a consistent comparison of human and animal that can be found symbolically in the villager’s masks and in the animals that are burned to death along with Sergeant Howie. This sentiment is echoed in Lord Summerisle’s monologue toward the beginning of the film, where he praises animals for their lack of philosophical compulsion. Summerisle also alludes to a struggle of dominance for man over beast when expressing to Howie that the game of the “hunted leading the hunter” has come to an end. While it’s hard to say whether this was intended as a critical look into harmful hierarchies established through religion and colonization, by design or otherwise, it certainly lends to the helpless and trapped quality behind the concept of necessary sacrifice.

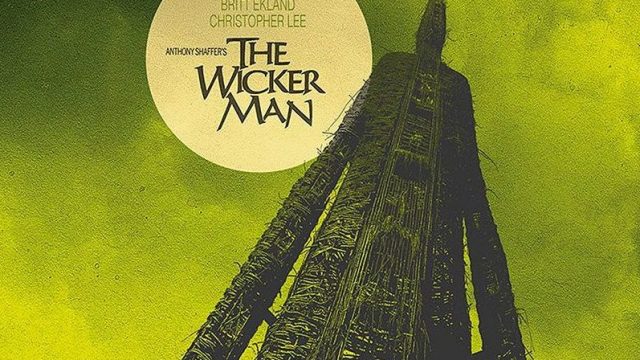

The Wicker Man plays a game of hiding in plain sight, which can be evidenced even in the title of the film itself. The wicker man erected by the Pagans is part of the breathtaking quality of the movie’s final reveal. The movie’s tense, terrifying moments are all portrayed without gore or visible violence. Despite the pervasive feeling that something is amiss, no one has been killed or maimed up to this point. The chilling nature of Howie’s death, and the duality of the Pagan religion, is elevated by the understated whisper of harm throughout the rest of the film. The giant wooden structure shaped as a man has now become the tomb where Howie meets his end. Even as the flames climb, he insists on attempting to shout his own Christian prayers over the ritualistic chanting and singing of the villagers down below. As the camera pans out from the burning effigy to settle on a glowing orange sunset, the complexity of relative religious morality remains a dancing flame in the mind of the viewer.