Calvin and Hobbes left the funny pages shortly after I was born, but I was still lucky enough to discover it when I was around the same age as Calvin. My parents had received a near-complete set of book collections as a wedding present, and my dad would sit me on his lap and read from The Lazy Sunday Book (his rendition of Calvin, as a “song sparrow,” belting out “On Top of Spaghetti” always had me in stitches). When I learned to read for myself, we had moved to a new house, and I trekked through all the books (out of order, unfortunately) as we unpacked them. Once I was old enough to have some money of my own, I filled in the gaps in Mom and Dad’s collection with the later, two-by-four shaped volumes at the end of the series, after creator Bill Watterson negotiated for a fixed half-page every Sunday. I still think those are the best, partly because of Watterson’s increased creative freedom, but mostly because they’re the ones I read after I developed the critical faculties to appreciate them.

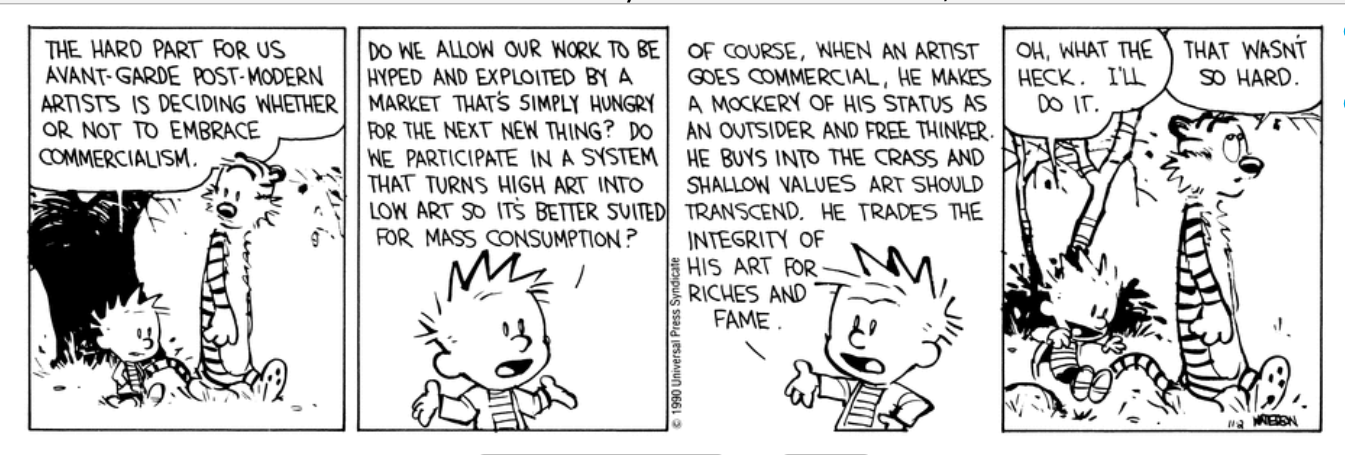

In 1990, Watterson was deep in the thick of those negotiations. Universal Syndicate wanted to turn his characters into a merchandising cash cow, and he was doing everything he could to fight it. His refusal to budge on his principles for the potential of a multimillion-dollar payday, his decision to end the series at the height of its popularity five years later, and his current Salingerian reclusiveness make Watterson a strange figure: an uncompromising artiste in an inherently commercial and artistically limiting medium. All he had was four little boxes a day, more on Sundays, all of it destined to end up as birdcage liners just 24 hours later. But as for what he did within those parameters, art is the only name for it.

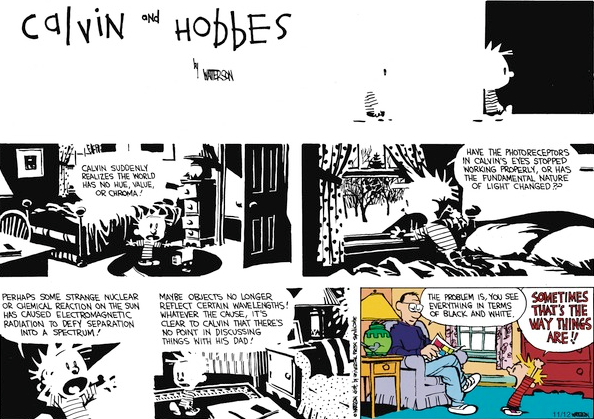

He drew from his arguments with his bosses for one of his most artistic strips. They claimed he was seeing everything in black and white, so he forwent his weekly dose of color to literalize that in a striking, high-contrast image of a black-and-white world. But in some ways, the syndicate was right. Charles Schulz had proven it was possible to create a deeply personal masterpiece while allowing fans to show their appreciation with a variety of products. The only other comparable merchandise juggernaut in comics is Garfield, and that was never intended to be anything more. Over in the sister medium of comic books, writers like Grant Morrison and Al Ewing have proven it’s possible to reinvent characters that appear on everything from pajamas to potholders in strange and daring ways.

And as a result of the inability to buy official merchandise, a bootleg market cropped up, eventually leading to the current ubiquity of “Calvin peeing on whatever you please” windshield decals. This misappropriation of Calvin’s image did far more harm to the public image of Watterson’s artwork than any stuffed Hobbes ever could — and without any of their own products to compete with it, neither he nor Universal had the legal standing or financial motivation to do anything about it. (And Watterson apparently said no to making a movie with Steven motherfucking Spielberg, and I don’t know if I can ever forgive him for that.)

But looking at other media, Watterson’s stance becomes clearer. Look at all the genuinely countercultural musicians whose art has become advertising jingles and whose faces have become cuddly corporate mascots of controlled rebellion. Or look at Mickey Mouse, who has become so completely swallowed up in corporate branding it’s hard to remember he ever had a personality to begin with.

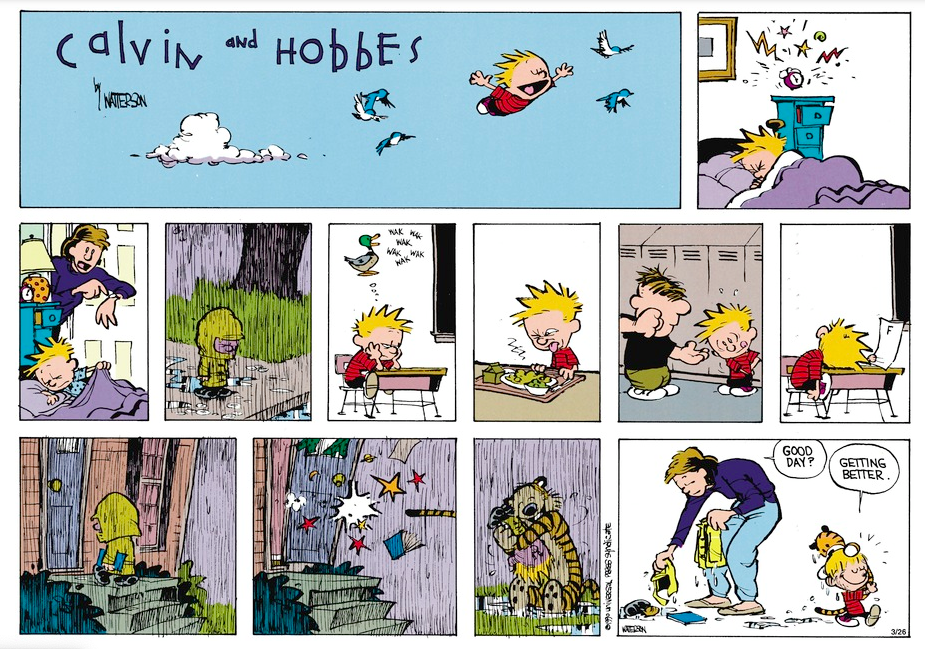

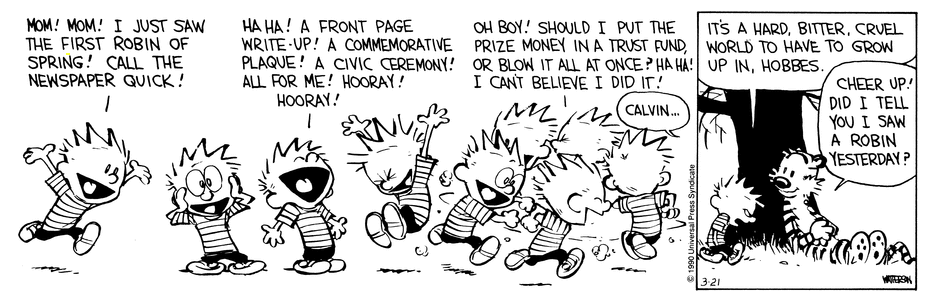

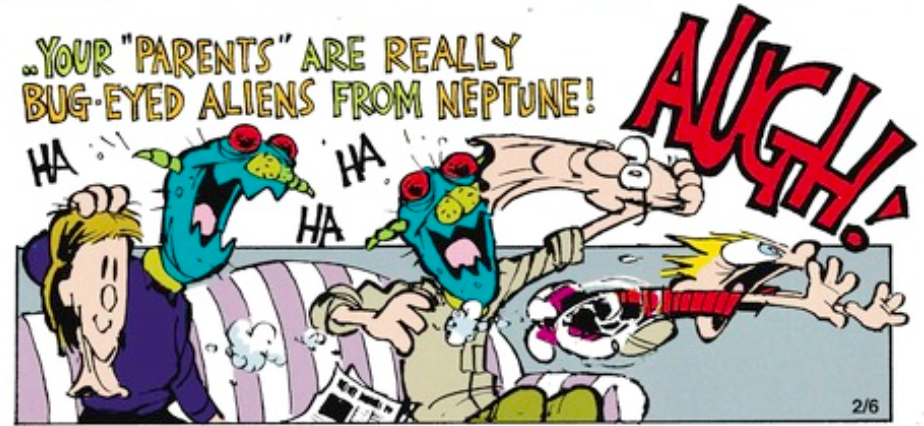

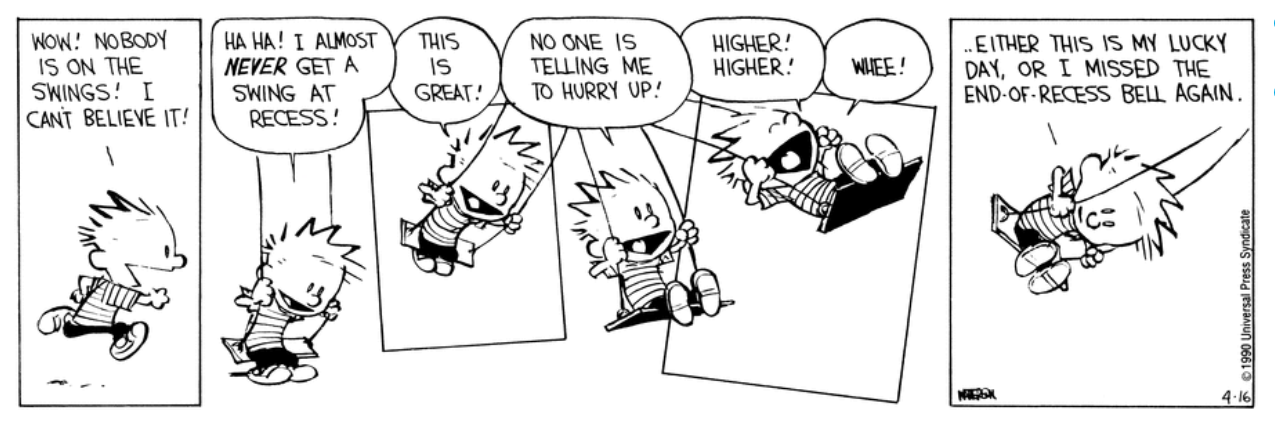

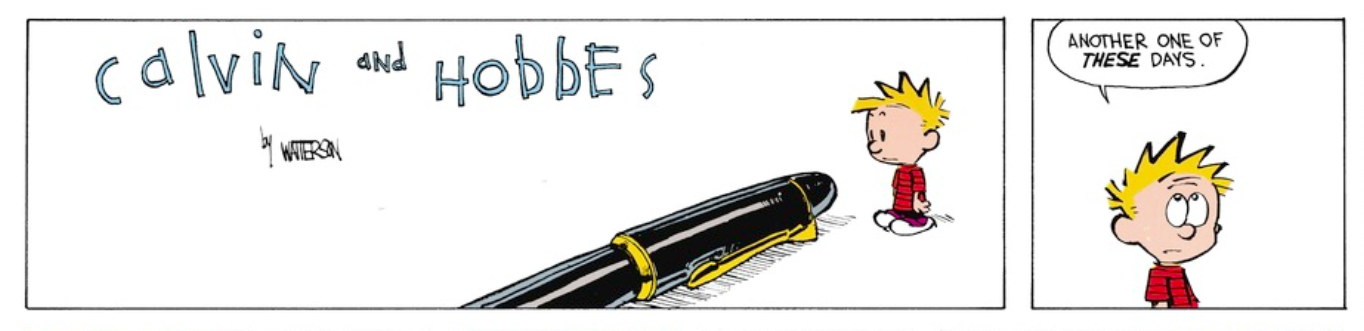

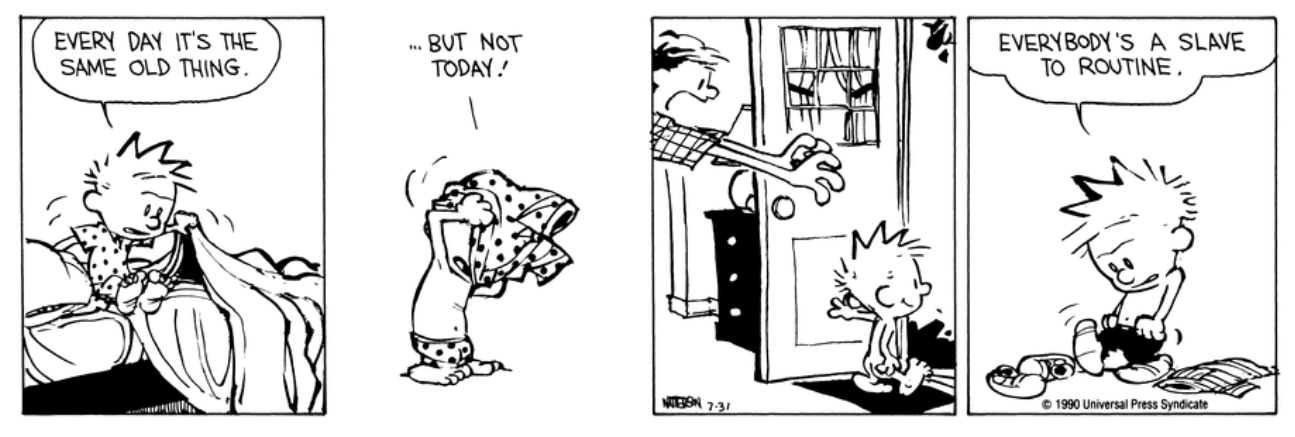

That certainly would have been an unhappy fate for Calvin and Hobbes. These are characters who have developed in a way only the protagonists of popular, serial fiction can: developing complexity through what you could more uncharitably call inconsistency. Depending on what the gag calls for, Calvin can be full of childlike wonder or jaded misanthropy, an intellectual discussing complex issues with an extremely improbable vocabulary or a perfect encapsulation of a real six-year-old. Over thousands of daily installments, all these mismatched parts add up to a greater whole. Calvin’s push-me-pull-you between awe and cynicism plays out over the whole strip. Watterson’s a bit too old to qualify as Generation X, but some aspects of Calvin and Hobbes reflect, or maybe even anticipate, that generation’s attitude. As Calvin himself put it, the world bores you when you’re cool, and the other characters are all defined by their different varieties of heavy-lidded response to Calvin’s shenanigans. Even in the face of impossible wonders, sometimes Calvin can’t muster up more of a response than this.

But Calvin’s imagination and sincere love for Hobbes (when they’re not at each other’s throats, anyway) give the strip a beating heart.

But Calvin’s imagination and sincere love for Hobbes (when they’re not at each other’s throats, anyway) give the strip a beating heart.

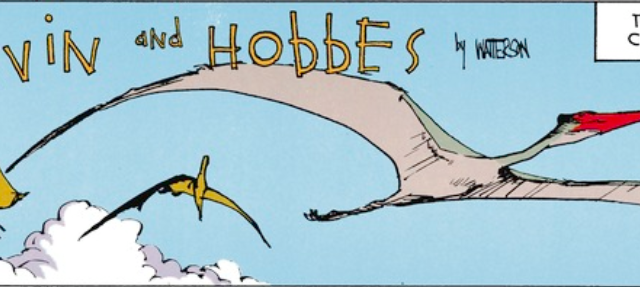

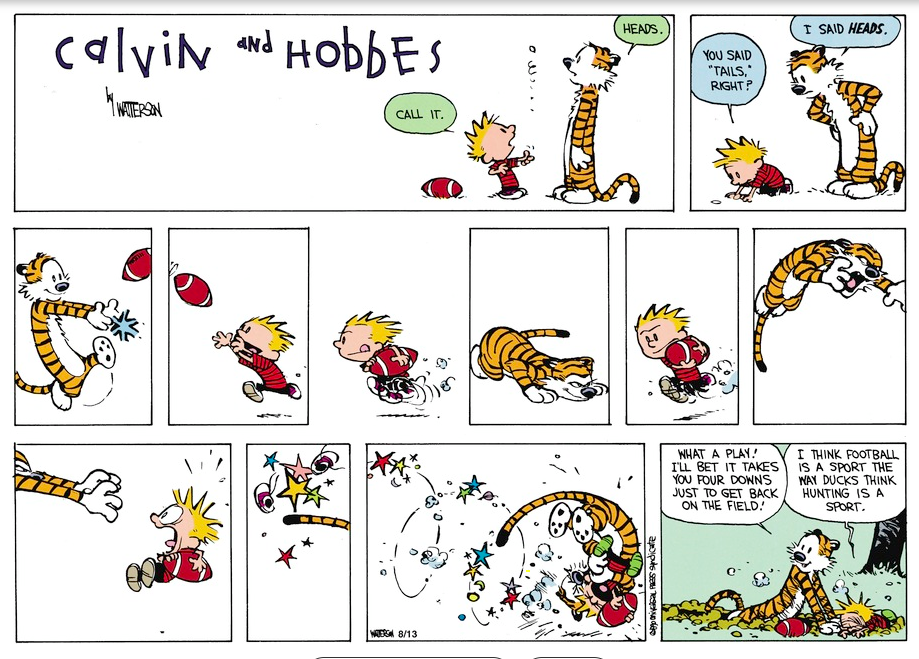

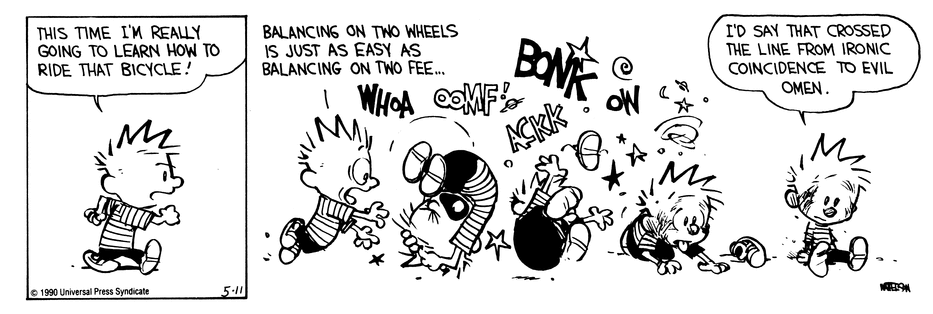

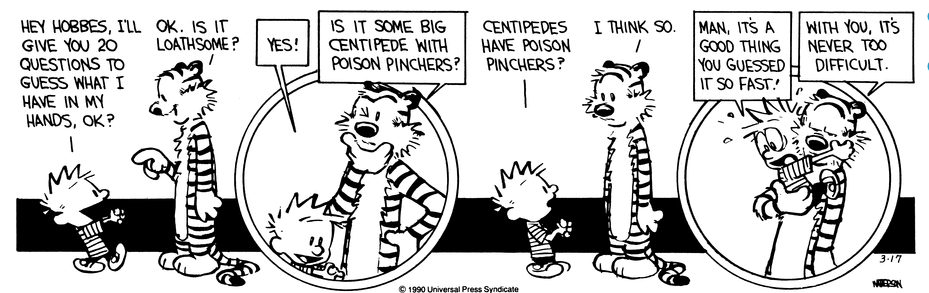

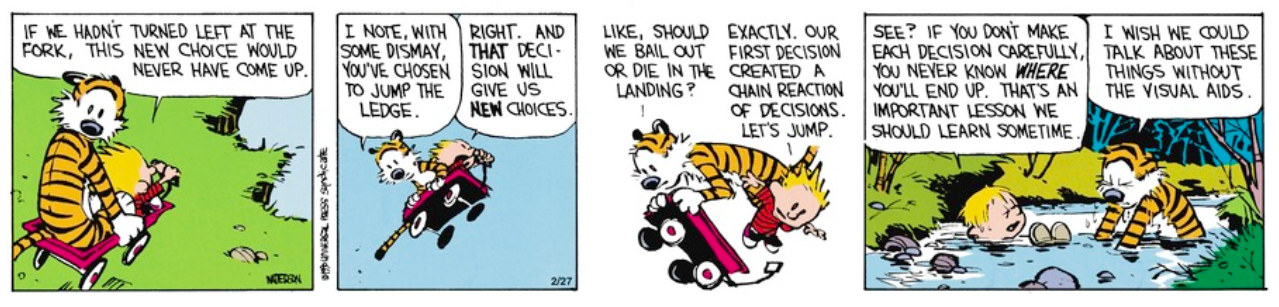

Calvin’s imagination is matched only by Watterson’s own, and if 1990’s strips (collected in Scientific Progress Goes “Boink” and Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons) don’t reach the heights later episodes would after he freed himself of the syndicate’s restrictions, they show Watterson straining to do as much as he could within them. The pre-half-page comics were bound to a set number of panels in a set number of sizes so that editors could chop them up and run them in different formats. Even before he was free to ignore them entirely, you can see Watterson rebelling against his parameters, dividing panels up or smashing them together, reshaping the panel borders or dropping them entirely.

Calvin’s imagination is matched only by Watterson’s own, and if 1990’s strips (collected in Scientific Progress Goes “Boink” and Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons) don’t reach the heights later episodes would after he freed himself of the syndicate’s restrictions, they show Watterson straining to do as much as he could within them. The pre-half-page comics were bound to a set number of panels in a set number of sizes so that editors could chop them up and run them in different formats. Even before he was free to ignore them entirely, you can see Watterson rebelling against his parameters, dividing panels up or smashing them together, reshaping the panel borders or dropping them entirely.

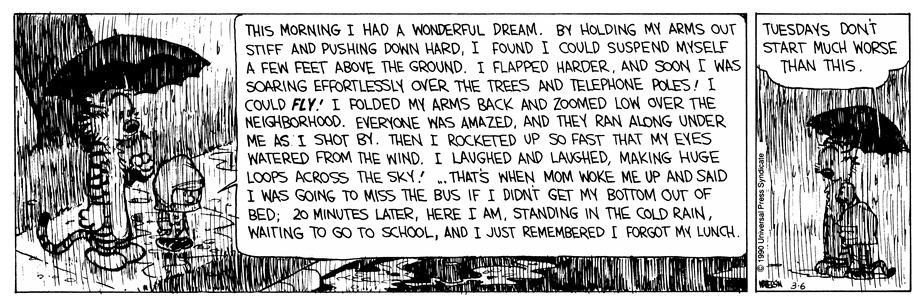

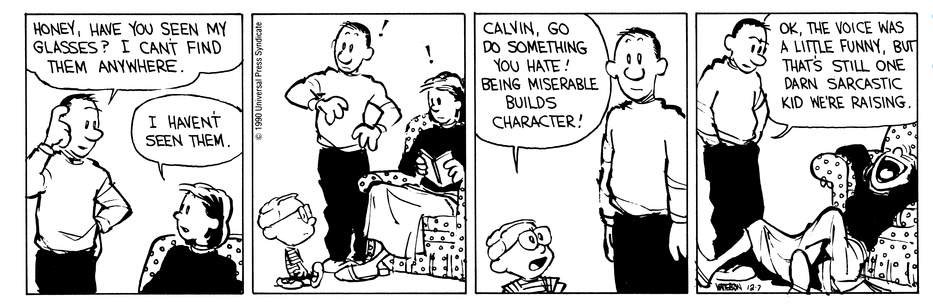

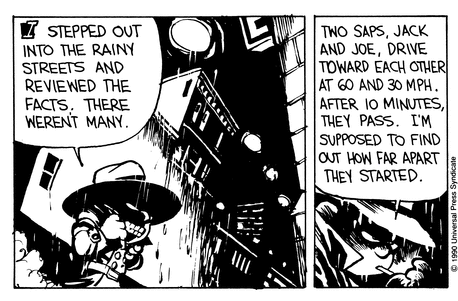

Other times, he expanded the text to tell an entire mini-story in two panels.

Watterson was obviously sweating under his bounds. The previous year, he had devoted an entire week to a mostly wordless, nearly abstract sequence of Calvin growing until he reaches the size of a galaxy. “My original idea,” he says, “was to do this for a month and see how long readers would have put up with it” — or more likely, to see how long the syndicate would let him get away with it. It reminds me of the gifted child who acts out because they’re bored studying below their level (so does Calvin, while we’re at it).

All of Watterson’s blood, sweat, and tears fighting the syndicate opens up the question of why, exactly, he bothered. By 1990, newspapers were far from the only game in town, and artists like Art Spiegelman, the Hernandez Brothers, and Frank Miller (may his credibility rest in peace) were proving that comics could be pretty much whatever you wanted them to be. More recently, books like Building Stories and In the Shadow of No Towers have come close to reproducing the dimensions of the early full-page newspaper comics that Watterson tried so hard to recreate.

He experimented with something similar in the anthology volumes (Sunday and the Essential, Authoritative, and Indispensable Calvin and Hobbes), expanding Calvin’s world with splash pages and poems that ignored the page-and-panel format altogether, all hand-painted in watercolor. Watterson even says in The Calvin and Hobbes 10th Anniversary Book that “I could easily have gotten more freedom and more money by abandoning newspapers altogether and publishing elsewhere,” but he isn’t forthcoming with the reasons he didn’t.

It’s true he’d lose his mass audience, but his refusal to merchandise suggests he didn’t much care. And the success of books like Maus, to say nothing of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which exploded from a self-published comic to the one of the era’s biggest multimedia phenomena, or Watterson’s own books — still in print almost forty years later! — suggests that audience would happily follow him into a new format.

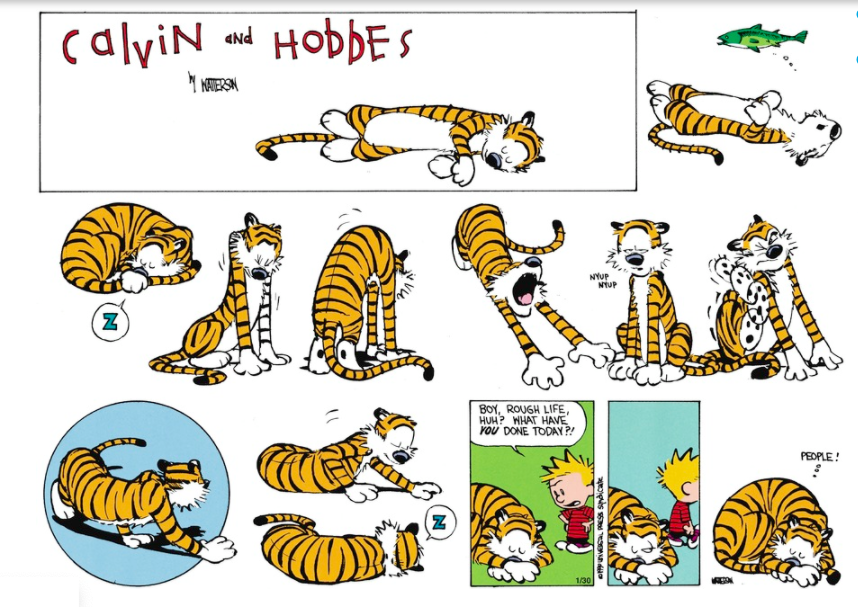

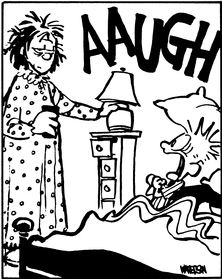

Whyever Watterson chose such a limiting art form, the artistry itself is above reproach. He may have resisted adapting his characters to animation, but on the page, they’re already incredibly animated, their bodies warping in motion and their faces in emotion, the mouths or trademark black dot eyes expanding to several dozen times their size.

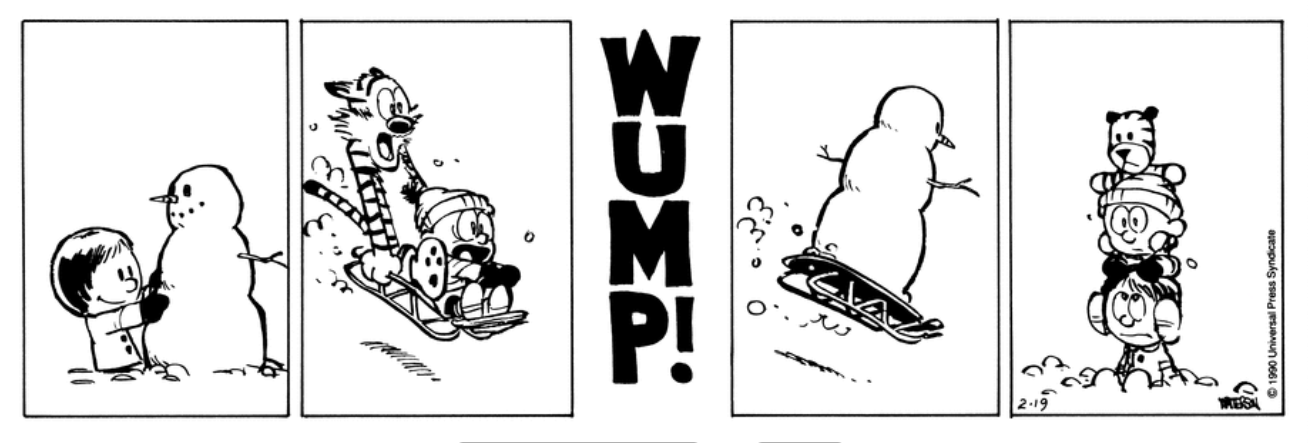

Like John Stanley, Watterson used the medium’s unique ability to combine the subtle and the unsubtle. 1990 saw the debut of the “noodle incident” running gag, which Watterson explains “is left to the reader’s imagination, where it’s sure to be more outrageous.” And it is, to the point where “noodle incident” has literally become synonymous with unexplained and inexplicable references. That approach is central to Calvin and Hobbes, which makes its outrageous gags that much more outrageous by only showing us the aftermath and preserves the reality of Calvin’s world that too much cartoon violence would shatter.

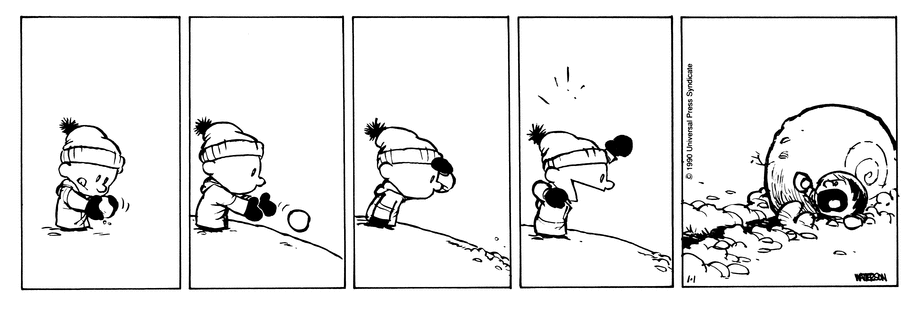

That’s especially true in this strip, which takes a limp gag and makes it hilarious by removing both the dialogue and the action. The basic concept is implausible even by the lax standards of cartoon physics, but by moving the cartooniest moment into the gutters between panels, replacing it with a giant “WUMP!” Watterson spins it into gold.

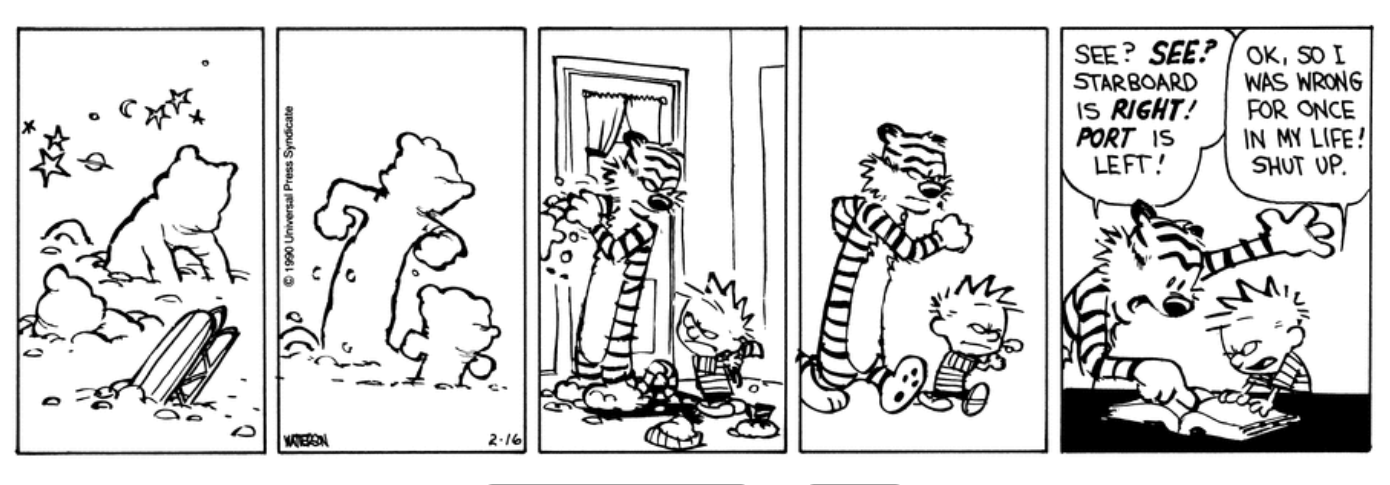

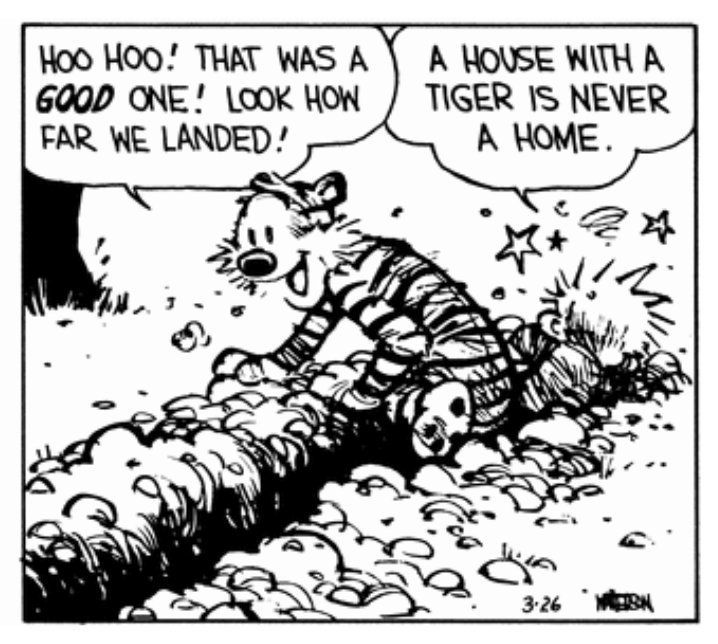

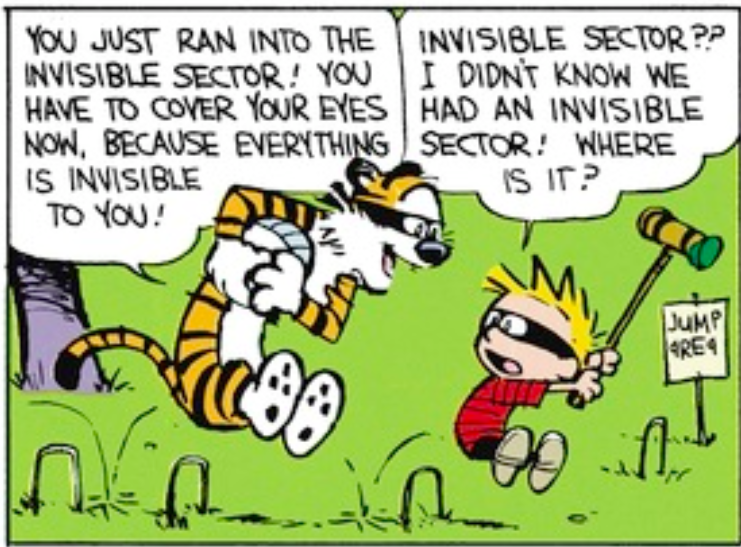

That approach is most evident in the many strips of Hobbes pouncing on Calvin. Sometimes, we see the impact, as both characters stretch like they’re caught in a black hole.

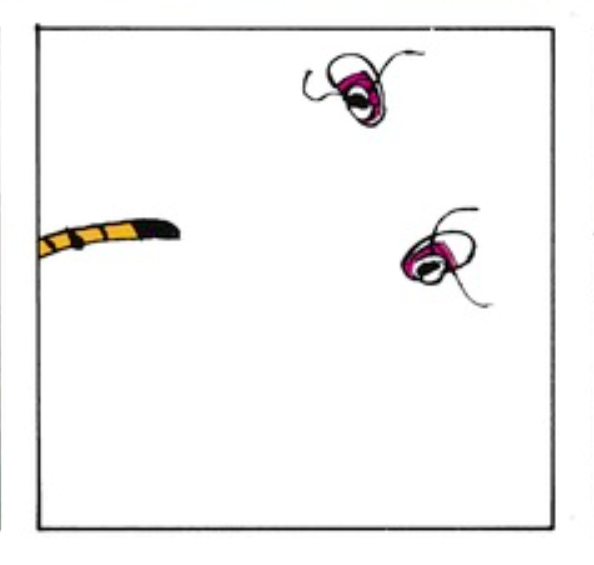

But more often, we only see the aftereffects, as Calvin’s clothes or shoes hang in the air behind them, gracefully floating as Watterson suggests their movement without most cartoonists’ motion-blur cheats, nothing visible of the characters themselves but the end of Hobbes’ tail.

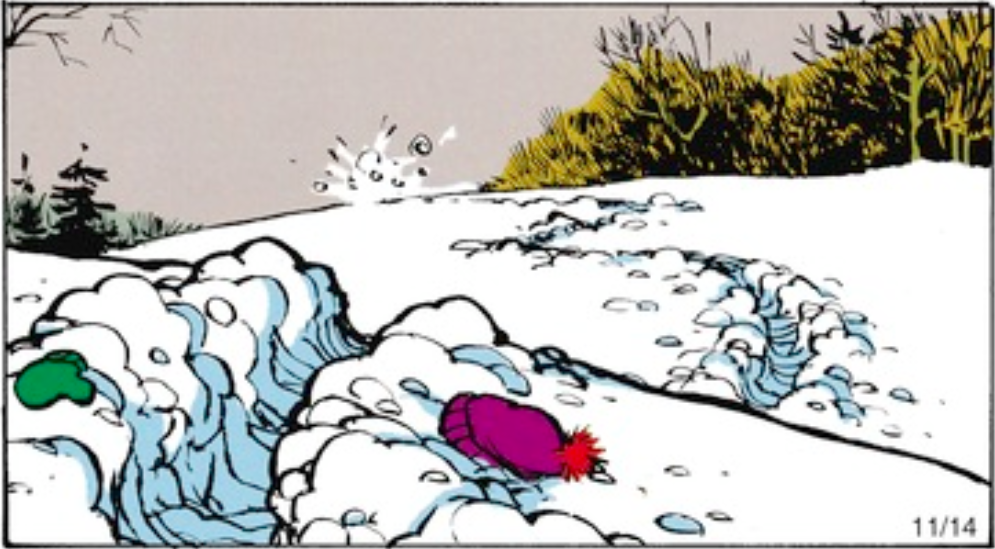

In some cases, Watterson uses the strip format itself to suggest movement, warping the panels to follow his characters.

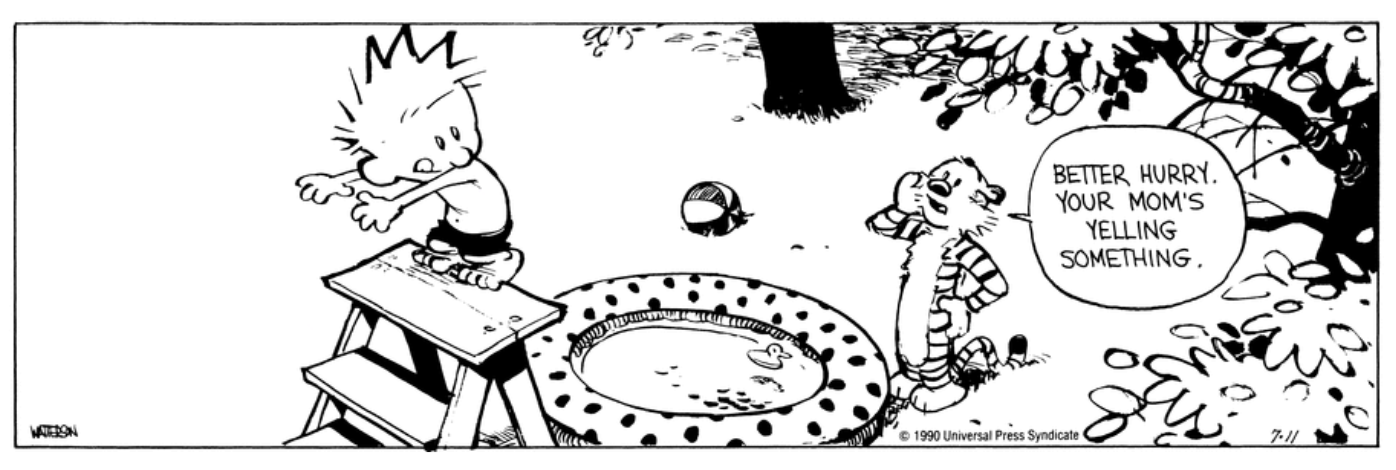

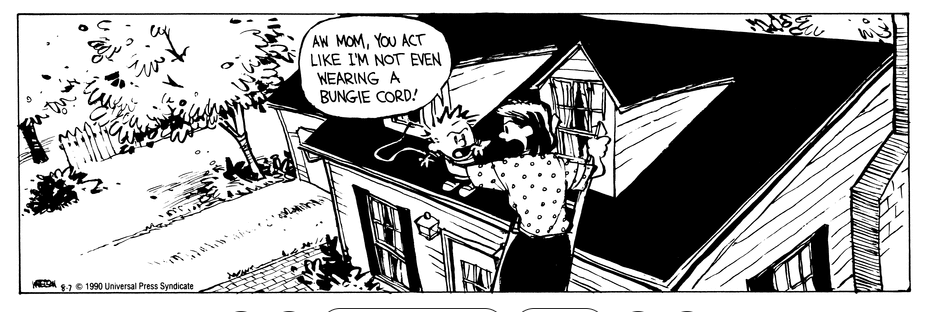

Other strips only show us one scene out of the middle of some bigger misadventure, drawing laughs out of our attempt to make sense of what circumstances could have possibly led there. “Your mom’s yelling something” is far funnier than any specific thing she could have yelled.

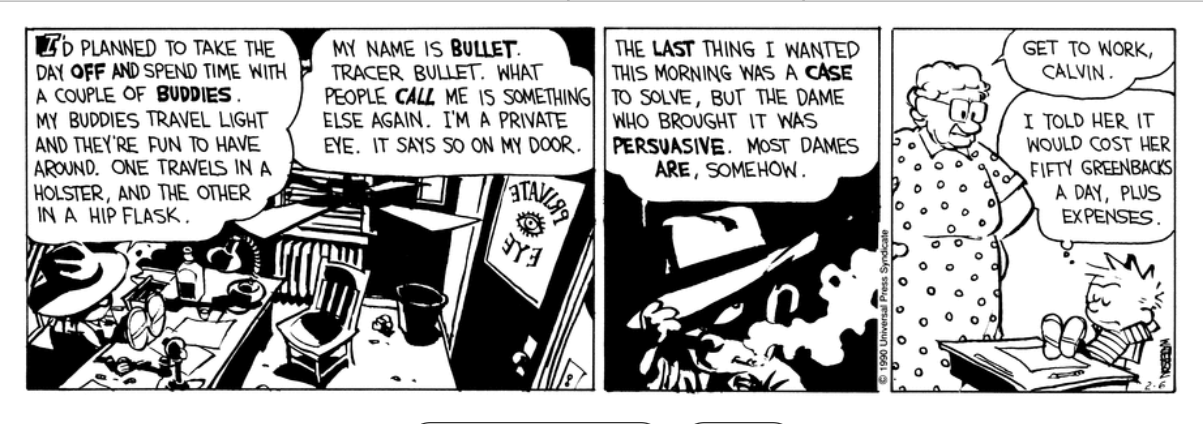

A lot of readers’ favorite part of Calvin and Hobbes is the extended storylines, which could go on for weeks and end up somewhere completely different than they started — Watterson himself admits “I never write stories with the ending in mind, because I want the story to develop a life of its own, and I want the resolution of the dilemma to surprise me.” One of 1990’s stories featured one of the rare appearances of Tracer Bullet, Calvin’s detective alter ego. “I don’t attempt them that often,” Watterson says. “I’m not at all familiar with film noir or detective novels, so these are just spoofs on the clichés of the genre.”

He’s too modest. Has there ever been any better hardboiled dialogue than “The inside of my head was exploding with fireworks. Fortunately, my last thought turned the lights out when it left” or “Susie had a face that suggested that somebody upstairs had a weird sense of humor. But I wasn’t going to her for laughs. I needed information”? Certainly, the artwork shows his familiarity with the visuals of film noir, reproducing the heavy shadows in gorgeously stark black and white. Sometimes, Calvin turns almost abstract as his outline is swallowed up in darkness.

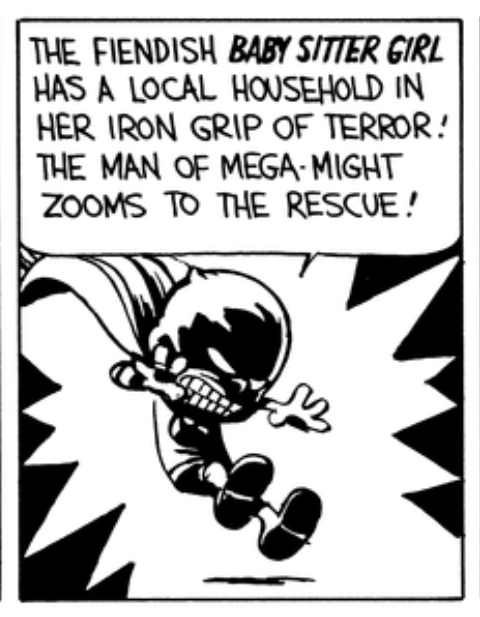

Calvin’s other alter ego, Stupendous Man, shows more experiments with shadow to create an odd amalgamation of Dark Age-style artwork and Silver Age-style bombast.

Another 1990 story is one of the few Watterson drew from his own childhood, and it’s easy to see its resonance with his adult life as he wrote it. When baseball season starts, Calvin’s bullied into joining the team, with disastrous results. There’s a bright side, though, as the final installment shows him inventing Calvinball, which only has three rules: you can never play the same way twice, you have to wear a mask, and you can’t question the masks.

It’s an addition to Calvin’s character that says a lot about him, and a lot about Calvin and Hobbes. In 1990, Watterson was chafing under the syndicate’s rules. By 1995, when Watterson ended the series, he seemed to have decided there was no way to create art for mass consumption without having to play by someone else’s rules and that he wasn’t willing to do that anymore. That would certainly explain his current reclusive lifestyle, especially if you believe the rumors that he torches his paintings as soon as he finishes them.

His departure was a great loss to the world of comics and of art in general. At least we’ll always have that decade’s worth of comics, in which he created a magical world. Let’s go explore it.

Want to subsidize Sam’s explorations? Then donate to his Patreon!

Want to subsidize Sam’s explorations? Then donate to his Patreon!