Was any director a better fit for New World Pictures than Joe Dante? Formed in 1970 by Roger and Gene Corman, the company’s goal was to make “low-budget films by new talent” before “distributing them internationally,” according to David A. Cook’s book, Lost Illusions. Corman provided many a first-time director with a chance to learn their craft directing schlocky movies, with several notable figures starting their career with him, including James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola and Ron Howard. This was Dante’s realm too, albeit with a better sense of playfulness in his works. After all, who can forget the memorable scene in Gremlins, when the movie’s story grinds to a halt in the town’s bar, allowing us to revel in the titular creatures’ behavior, acting as an anarchic corrective to the sleepy suburb? Featuring the cartoonish vermin as they get drunk, gamble and shoot each other, it provides the spectacle any self-respecting B-moviegoer might demand in a typical piece of schlock. The clever twist here is Dante figuring out how to combine elements, not only giving us what we want, but playing off our expectations as well.

However, before he could play in the studio sandbox, Dante had to prove his mettle at New World Pictures. According to a 2010 Entertainment Weekly article discussing the making of Piranha, Dante began his filmmaking career as a trailer editor, adding in footage of exploding helicopters to each preview, regardless of whether or not they factored into the plot. As Corman put it, “our trailers were better than the picture very often.” After proving himself as an editor, Dante was eventually able to secure a job alongside fellow trailer editor Allan Arkush, directing a movie called Hollywood Boulevard, about a Corman-esque low-budget movie studio. Following the success of that movie, which was the cheapest New World film produced to date,or a grand total of $60,000, Dante was able to fish around for a bigger project, picking something that had some more teeth.

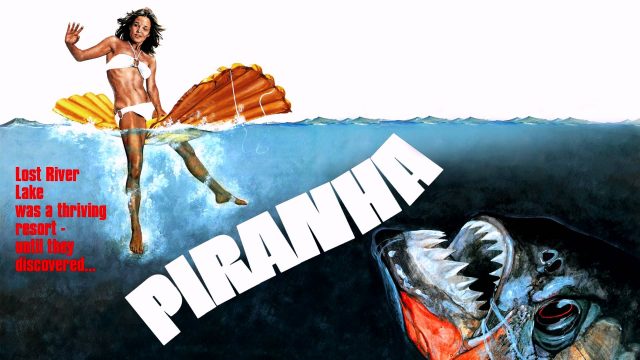

Released in 1978, Piranha was one of several movies to capitalize on the runaway popularity of Jaws, itself an enhancement on your typical creature feature. As one Universal executive said, “what was Jaws but an old Corman monster-from-the-deep flick?” Ironic then, that the studio which had taken the Corman movie mold and pumped it up to blockbuster status nearly prevented its B-movie rip-off from being released. Universal was prepared to issue an injunction against the release of Piranha, fearful that the film would cannibalize ticket sales from Jaws 2, which had been released earlier that year. Fortunately, Dante’s movie had a champion in Steven Spielberg, who held back the legal tide by speaking positively of the movie, according to Joseph McBride’s book, Steven Spielberg: A Biography. As a result, the movie was able to swim upstream, grossing $6 million in the U.S. alone, easily recouping its $600,000 budget.

Now that we’re done treading water, let’s move on to the meatier aspects of the story, barebones though it may be. One thing it is not is dull, continually moving forward, ensuring you never have to suffer from dead weight, or anything striving for—God forbid—art. The story begins in Texas, where we see a young, nubile couple doing the most romantic of activities: moonlight hiking through the brush without flashlights.

Fortunately, the two manage to avoid injury and sneak onto an apparently abandoned military test site. Given how it’s summer, the two of them are only too happy to take a dip in the compound’s pool, to ensure it “won’t be so funky,” in their sleeping bag. Only after the female hiker, Barbara, strips down to her underwear and nothing else do things go wrong, of course. At first, it’s only a nibble, which her boyfriend, David, assumes was a playful act. But those early bites soon morph into a feeding frenzy, the piranhas consuming both hikers. To borrow from another movie: Yes, Barbara, they’re coming to get you. Especially when you go for a swim in their tank.

The opening credits then begin to roll, meaning we’ve already received our money’s worth, taking in titillation, death and blood, while giving us that Jaws fix. The comparisons to that classic movie don’t stop there, with Piranha winking to its progenitor in the next scene. We get introduced to Maggie McKeown, played by Heather Menzies, deeply invested in a Jaws arcade game at the airport, as we hear that, yes, the white zone is for loading and unloading only, without a ready retort from Vernon.

Maggie is getting ready to head out into the wilderness for her next assignment. Working as a skip tracer, a position that hasn’t appeared in the movies too often, Maggie has been assigned to track down the two hikers. Her boss is worried about her, given how all her past assignments have remained strictly within the city limits. “I’m two-thirds bloodhound, I told you that when you hired me,” she says to put him at ease, before briefly panicking when she can’t find her plane ticket.

While the script, written by John Sayles, doesn’t necessarily have many straightforward gags, there are plenty of knowing moments that play off the expectations of your typical B-movie. Take for example a scene on the river after Maggie has accidentally released the piranhas, in an attempt to locate the hikers’ bodies, studiously absent from the pool even though a dog skeleton remains present. A father and his son are attempting to fish in the river, but the boat is caught on something, which naturally means the father got tangled up in it too. Short of ringing a dinner bell, it’s hard to find a better set up, where the punch line is the father getting dragged into the water by the hungry horde. The audiences are satiated with an all-too-perfect set-up, and the fish get their meal. Bon appétit.

Dante and Sayles also play around with B-movies’ penchant for titillation. At the midpoint of the movie, Maggie and her deputized civilian, Paul Grogan (Bradford Dillman), whose primary character traits are drinking and surliness, find themselves detained by the military. A colonel is interested in hushing up the whole affair, keeping the two in a tent under guard by a military policeman, played by Sayles. Grogan asks her to come onto the soldier to keep him distracted long enough for him to jump the MP. But Maggie spots one potential flaw in the plan, asking, “but what if he’s gay?” After a short pause, he decides that if that is the case, “I’ll distract him.” Compare this to any other B-movie and you can see the influence Dante had on the production. Ordinarily, you’d expect the woman to expose herself, the guard would get knocked out and we’d move on. But Dante was clearly more willing to play with the form, delaying the expected by poking fun at it first.

Needless to say, this is not a movie that takes itself seriously, and it implores you not to either. One can spot Dante’s predilections towards tearing down any pretensions about the movies. As he seems to say in this film and many others, the movies may be capable of great beauty, but where’s the fun in that? Take what might arguably be one of Piranha’s most iconic scenes, set at a riverside camp for young children. In most creature features, these kids would be off-limits, with a nervous producer concerned about good taste and decency. But Dante plows ahead, turning the kids, set up in inner tubes, into a floating smorgasbord. One can imagine Spielberg chuckling at this scene when he first watched it, seeing someone with the gall and willingness to do what he couldn’t with Jaws. Welcome to the world of Piranha, where nothing is sacred, and even the kids get turned into fish food.

As with most monster movies produced on the cheap, there’s always a concern that the effects won’t live up to the hype. While the principal goal of New World Pictures was making a quick profit, it’s understandable that all the awareness of B-movie traditions can come to naught if you spot a zipper on the monster, moving it from a fun movie to a laughable one. Fortunately, two men were able to help bring the mutant piranha to life, proving their talents would guarantee them a spot in movie history. Phil Tippett, known for his work on two of the original Star Wars movies and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, was the creature designer and animator while Rob Bottin provided the specialized make-up. As a result, the team was able to replicate existing piranha footage of the time, according to Dante.

While Piranha isn’t great art, it’s never trying to be, and the movie’s sense of play is a big reason it has remained so durable. This isn’t something that can be replicated, though it is one of Corman’s more successful franchises, even spawning two remakes and one sequel. Yet the charm of the original still holds water. They say a school of piranha can skeletonize a cow in several minutes, especially if it’s starving. It’s hard to say if the movie Piranha has the same effect on a cow, but if nothing else, it will remain an udder delight, skeletonizing any lesser imitation for years to come.