2007 was a formative year for my relationship with the movies. It was the year I chose to take them seriously, as an art form instead of solely as entertainment. Sure, I had enjoyed the popular delights of lightsabers and magic wands, bullwhips and superhero tights. But movies had become the newest facet of my developing personality, and I was eager to see what else was out there.

Fortunately, 2007 was probably one of the best times to explore cinema. With the Coen Brothers’ Academy Award-winning No Country for Old Men, the eminently watchable legal thriller Michael Clayton, Paul Thomas Anderson’s meme-able There Will Be Blood, and my personal favorite, Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz, it was a superb gateway into a more expansive set of directors, genres, and styles.

However, there was a snag. While many of these films have continued to take up real estate in my brain, the only way I could experience them was through trailers and the even more memorable mash-ups (including an absurdly perfect music video using clips from There Will Be Blood cut to Kelis’ song Milkshake) on YouTube. Due to each movie’s R rating, I couldn’t see most of these until they completed their theatrical run and I could get them to my parent’s house on DVD.

But there was still one movie I was able to see in a theater due to its PG-13 rating. Granted, by the time I saw Breach, it was at the last-run dollar theater outside the city, and my Dad and I had to sit in the corner of the very front row. But it still left an impact on me. You could call it my cinematic Rubicon, with The Dark Knight and later Ponyo cementing the idea of giving movies (and later television) more thought as an art form than just something to pass the time.

We start the movie not with actors, but with a performer of a different variety. It’s former Attorney General John Ashcroft giving a press conference in early February of 2001. As he announces the end of an internal FBI investigation, including the arrest of one Robert Hanssen, he notes how a “very serious breach” has been closed.

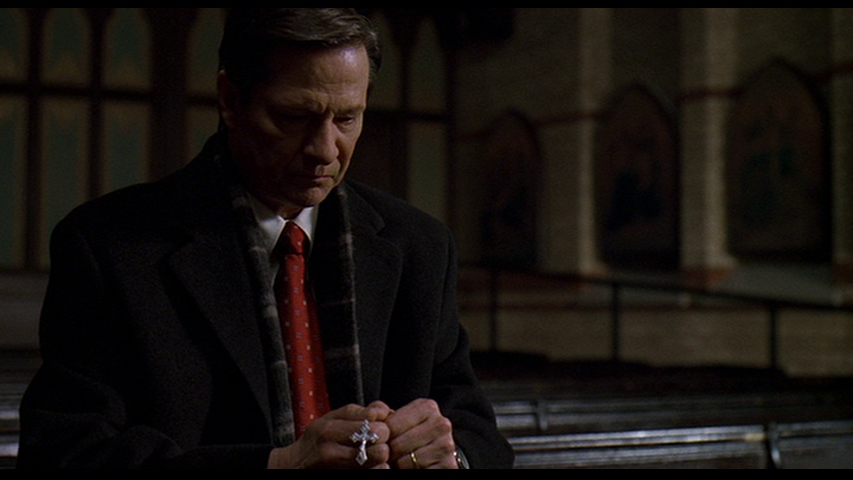

Following some statements from Ashcroft about American freedoms being targeted by external forces (somewhat hypocritical, given what followed), we jump back two months. In a Catholic church, set to the melancholy, sparse piano score by Mychael Danna, we meet our central, doomed figure, praying with a rosary.

Perhaps the greatest strength of this movie, upon re-watch, is Chris Cooper’s performance, which seems to slowly transform throughout the movie. Starting out e with a slight air of sadness, Cooper slowly reveals additional layers to us, without ever giving us the key to understanding this guy. Hanssen is a cipher, who can play the hard-ass boss, loving family man, zealous proselytizer, and more. No wonder I was pleasantly surprised when I saw Cooper in The Bourne Identity a few years later. Given all the unique flavors of Hanssen Cooper was able to play, who’s to say he couldn’t run a top-secret assassin ring inside the CIA, in addition to spying for the Russians?

If Cooper is the magnetic presence around which the movie revolves, who is his opponent? The one who helped bring down an agent with over 20 years of experience? Why, a young upstart recruit, one with the ambitions but not the means to become an agent. Enter Eric O’Neill, played by Ryan Phillippe, our Clarice Starling, but for office intrigue instead of serial killer pursuit.

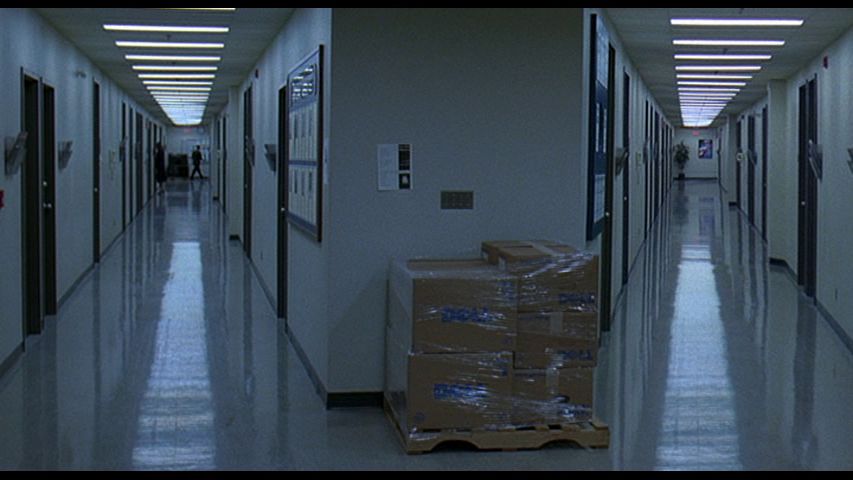

Aside from Cooper’s casting, one of the most effective storytelling choices is to portray the FBI as unappealingly as possible. Forget any high-tech gadgetry or moody lighting. This is the FBI by way of Office Space, complete with a small role for Gary Cole as another agent (though middle manager would be equally apt), sans the trademark Lumbergh glasses.

Billy Ray’s direction enhances that feeling, avoiding any showy direction or flashy editing. Tak Fujimoto’s cinematography is equally effective in that regard, adhering to a realistic look, complete with the flat, washed-out lighting you would get in any office. Forget the thrill of chasing criminals, or the suspense that comes from spying on a foreign country, the movie implies. The real battles are for who gets the nicer corner office with a window, or the arcane turf battles that take the form of canceled meetings.

Yet, while the minimalistic style is relatively effective in portraying these imposing institutions as petty, vain, and incompetent, there is a limit. Unlike Veep or In the Loop, both of which also highlighted how institutional incompetence and missteps can cost lives and resources, jokes are few and far between. This should be expected, given how Ray has framed this as a thriller, but there have been more effective movies portraying bureaucratic skullduggery, ones willing to push the stylistic boundaries slightly more. In All the President’s Men, for example, Deep Throat is lit as a phantom by Gordon Willis. He can appear and disappear in the parking garage without ever needing to do anything as dull as walking, and the movie’s all the stronger for it. Meanwhile, Breach keeps things cut and dry, even though Hanssen was clearly anything but.

While the look of Breach didn’t stick with me as much as similar movies had, the script, as written by Ray, Adam Mazer, and William Rotko, does an effective job of highlighting how draining and crushing it can be to work at the FBI. For O’Neill, he must wall off the secrets he’s accumulated from his wife Juliana (played by Caroline Dhavernas with a touch-and-go Eastern German accent), while dealing with demanding, difficult bosses. Laura Linney, playing a senior agent spearheading the investigation, has no social life (or even cat, it turns out) to speak of and has fully committed herself to the institution. As for Hanssen, he’s hardly a role model, often demeaning O’Neill at work before turning around and intruding into his personal life. No wonder O’Neill left the Bureau right after his boss’s arrest.

Breach is, ultimately, a minor work for me, one that represents a gateway which led to more interesting fare. Yet Cooper’s performance still stands out, to the point where I had to mentally readjust when the actor arrived onscreen in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. Breach provides no easy, straightforward answers regarding Hanssen’s actions. Even after getting arrested, he doesn’t explain himself to Dennis Haysbert’s Assistant Special Agent-in-Charge. Instead, he posits a question, referring to Aldrich Ames, though he may as well be speaking about himself.

“What good does speculating do? He spied. The why doesn’t mean a thing.”

That may be as fitting an epitaph for his career as a mole as anything. For Hanssen, who spent decades pretending to spy on the Soviets before turning around on the U.S., the rationale for doing so was immaterial, the movie suggests. Even after the Cold War had ended, he was the spy who refused to come in from the cold.