“Sometimes your worst self is your best self.” – Frank Semyon

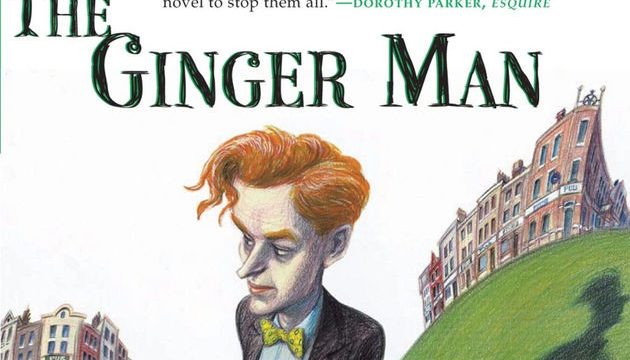

J. P. Donleavy died last year, at age ninety-three. As expected, his obituaries invariably made mention of The Ginger Man, a debut novel that anticipated and overshadowed his entire body of work to come: it’s ribald, bewitching, evocative and achieves a kind of refined crudeness that miraculously avoids being tonally confusing. That is to say, it’s refined in manner but crude in content, like a cherubic serenade emanating from a pile of trash. It’s also hilarious.

Sociologists (and more than a few English teachers) have suggested that there is a correlation between being “a reader” and possessing higher-than-average levels of empathy. This is presented as wholly positive, though it can sometimes be a curse. The Ginger Man places us squarely within the existence of a sociopathic hedonist, and the people who have the misfortune to meet him are kept at a distance: at best they’re temporarily amusing; at worst they’re obstacles to be overcome. Finding oneself in the head of this sort of character is not going to be everyone’s cup of tea, but the writing itself is so beguiling, and the laughs so consistent, that I’m quite happy to leave others to fret about any problematic elements.

In the book, Sebastian Dangerfield and his associates face and/or initiate all manner of mayhem, most of it fueled by Power’s Gold Label and stout. Sex and violence are general. Lies and betrayal are on every page. His wife and infant daughter alternately abandon, and are abandoned by, him. His one-eyed friend O’Keefe miserably pines for his first piece of ass. Miss Frost’s respectability is tainted when she is seduced by Dangerfield. Percy Clocklin muses about unnatural relations with farm animals. Mary wants Dangerfield’s “big tree of love” at every turn. Egbert Skully just wants his rent money. Dangerfield, unparalleled in the art of walking between the raindrops, avoids creditors while anxiously awaiting news of his father’s imminent death and a possible financial windfall. There’s an impromptu trip to London. Each page turn shoves, everyone (including the reader) inexorably towards chaos.

It’s hardly a didactic book, but I’ve learned a lot of lessons from The Ginger Man. Probably the most lasting and significant one has to do with the transactional nature of human relationships – and the lurking potential of turning one’s life into a waking nightmare should one take this notion to its absurd conclusion. (A close second would involve the necessity of maintaining dignity while swimming in a sea of debt.) The Ginger Man presents id without end, amen, amen. And since it doesn’t deign to editorialize about the amorality of its scoundrel antihero, it’s not likely to move up (or even retain its position at #99) on Modern Library’s “Hundred Best Novels of the 20th Century” list, should it be revised. Such is the uneasily moralizing nature of criticism in 2018.

But that’s not to suggest that the novel was received any more favourably in 1955. Unscrupulously published as pornography in France, banned in both Ireland and the U.S. for a time and expurgated for years to come, Donleavy himself would chronicle the tumultuous journey of his debut work in The History of the Ginger Man, and describe what fortified him in the face of adversity:

Ah, but what about literature and art. The hope to be part of which throbbed in every citizen’s heart. And made the excuse for him to go on living the next day and the next with the indifferent present being made tolerable by adorning the days ahead with rosy dreams. These, for target practice, always being promptly shot down in flames by your listeners, who in a public house, need have no mind for having to please a host or hostess.

Although written some forty years after the original novel, the above passage displays classic Donleavy construction: begin lofty and head for the ditch. Witness the opening of The Ginger Man itself:

Today a rare sun of spring. And horse carts clanging to the quays down Tara Street and the shoeless white faced kids screaming.

If all modern writers are the misfit sons and daughters of James Joyce, Donleavy was clearly vying for a more direct kind of lineage. The clipped stream of consciousness narrative style that followed Leopold Bloom through Dublin is in evidence, but where Ulysses can seem like work, The Ginger Man doubles down on broad comedy, scandalizing the reader with its brazen luridness. Along with Ireland, and problems of censorship, the two works share a seeming disdain for traditional plotting. However, Donleavy doesn’t shy away from singular dramatic moments as Joyce does, and The Ginger Man has a looser structure, displaying none of Joyce’s obsession with densely packed symbolism or allusion. Instead, Donleavy is concerned only with rendering events with a lyrical immediacy:

Dangerfield was running like a madman down the middle of the road with the cry get the guards pushing him faster. Into a laneway, bottle stuffed under his arm. More yells as they caught sight as he went round and down another street. Must for the love of God get hidden. Up these steps and got to get through this door somehow and out of sight quick.

Heart pounding, leaning on the wall for breath. A bicycle against the wall. Dark and racy for sure. Hope. Wait till they are by the house. Feet. I hear the heavy heels of a peeler. Pray for me. If they get me I’ll be disgraced. Must avoid capture for the sake of the undesirable publicity it will produce. Or they may take clubs to me. Suffering shit.

Donleavy was a master of the sentence fragment, but he also artfully avoided expressive punctuation. I have no idea how literary humour functions, exactly, but I do know that his clinical, disinterested rendering of human thought and speech works like gangbusters:

“God damn this house. It’s the size of a closet and I can’t even find my own foot in it. I’ll break something in a minute.”

“Don’t you dare. And here, a revolting post-card from your friend O’Keefe.”

Marion flicked it across the room.

“Watch my correspondence. I don’t want to have it thrown about.”

“Your correspondence, indeed. Read it.”

Scrawled in large capitals:

WE HAVE THE FANGS OF ANIMALS

“E. O aye.”

This terseness yields some of the book’s finest moments. Upon reading a (only slightly exaggerated) newspaper account of his own whimsical drunken carnage in a pub the night before, Dangerfield responds with a single word, his misplaced moral outrage palpable:

“Libel.”

There’s a balance between solemnity and profanity that is central to all of Donleavy’s work. Arguably this is manifested most gracefully in his debut novel; later works sometimes veer sharply in one direction or another, with mixed results. Donleavy is a great (or possibly faintly tragic) example of an author who emerged fully formed, then spent the rest of his career riffing on the themes and character-types established at the outset. Obviously, for at least one reader, this consistency is more feature than bug, but it’s also useful for the neophyte: if you’re not enchanted by the first few chapters of this book, you can comfortably be Donleavy-free for the rest of your life. (Although his non-fiction venture, The Unexpurgated Code: A Complete Guide to Survival and Manners, is indispensable.)

I first read The Ginger Man at the age of twenty. It cast a powerful spell over my life for the next ten years or so, and traces linger today. It obsessed me. Someone who’d always refused to revisit books, thinking it indulgent or a waste of time, I read the novel nineteen times in fairly rapid succession. I bought copies for my immediate family and friends. No doubt it indirectly inspired my most impetuous and foolhardy ventures – fathering a child through carelessness (good); concurrently getting engaged to another woman (bad); drinking and stirring up all manner of shit while affecting the speech and general conduct of a stalwart gentleman (pending). The online handle that I’ve had for the last twenty years was inspired by a subsequent Donleavy novel, The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B. In probably the most embarrassing example of my mania, last summer I followed a car sporting the vanity plate “GINGRMAN” into a lot, breathlessly asking the driver if he loved Donleavy’s work as much as I.

Ron Howard: He didn’t. Instead he offered a rather poignant tale of discrimination. Apparently so-called “gingers” are not allowed to donate sperm, and children with red hair and freckles are often the last children to be selected for adoption.

The exploits of the title character are largely based on the experiences of Gainor Stephen Crist, another American studying at Trinity College courtesy of the G.I. Bill. By most accounts Crist was a handsome, randy rogue – endlessly charming and erudite – and positively up to his eyeballs in debt. Although not nearly the irredeemable blackguard that Dangerfield is on the page, chaos did seem to follow Crist everywhere. But his powers of persuasion and highly evolved sense of survival allowed him to garner credit in some of the most parsimonious pubs in the country. His literary avatar lives on, a devilish inspiration to anyone who’s felt compelled to seek fortification in spirits, run headlong from natural consequence, or find consolation in depravity while affecting an upright posture.

God’s mercy

On the wild

Ginger Man