Oh, mother! Oh God, mother! SPOILERS! SPOILERS!

(There are three phases to this review’s SPOILERS, and they’re marked below. If you haven’t seen the film, I strongly encourage you to do so before you get to the last, or even the second-last, phase.)

“I know your kind, he said. What’s wrong with you is wrong all the way through you.”

– Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

“Ninety-nine years is a long, long time.”

– Pam Grier

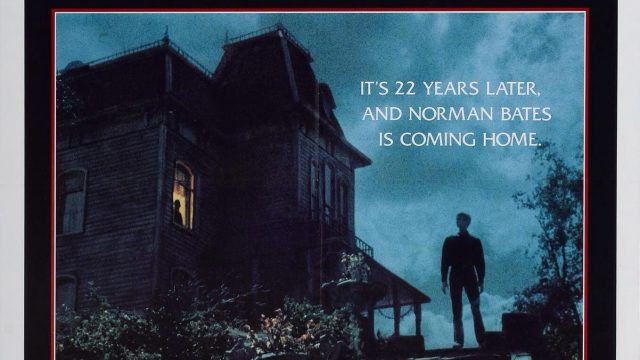

Psycho II opens with a reprise of its predecessor’s most iconic scene. This is a misstep, and it suggests some sort of fundamental lack of confidence in the entire venture. Perhaps even in 1983 – prime sequel time, to be sure – Universal and director Richard Franklin understood that they would never escape the silhouette of Alfred Hitchcock and his masterpiece. As foregone conclusions go, this is a hard one to take issue with. Even after the follow-up arrived in VHS rental houses, I have vivid memories of its cover offering the frank reassurance that the film does, indeed, contain the classic shower scene. Hardly dignified, and one could be forgiven for thinking it some sort of consolation prize shoehorned into a film that must be quite dire.

Psycho II is not dire. At first blush it sounds completely superfluous; worse, its very existence threatens to undermine the power of its predecessor. Fortune smiles on unlikely enterprises, however, and Psycho II is a very good little film.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score does much of the heavy lifting throughout, just as Bernard Herrmann’s did with the first, though their respective loads are quite different. Herrmann’s “black and white” score utilized strings exclusively, and tended to pitch toward states of near-panic, if not outright frenzy; Goldsmith uses piano to tentatively establish melancholy, then complements it with eerie synth and delicate orchestration, nudging the film into the realm of a sad haunted house tale. Yes, the deserted Bates place would be a literal representation of this, but we also have the now-vacant corners of Norman Bates’ (Anthony Perkins) rehabilitated mind, once occupied by the mother half of his personality.

This main title theme is the first thing one notices, the old Bates home looming in the background. It’s a beautiful piece of work, marrying profound sadness with soaring melodiousness. It also establishes the profound regrets and dim hopes of the central character. Norman spends most of the movie behaving like a shy adolescent – and good for him, because when he lets the mask slip, he’s fucking terrifying – and being locked up for twenty-two years seems to have banished his mother persona, or at least sent her into remission. But the character is hardly “good as new.”

SPOILERS – PHASE ONE

In a classic example of hero/villain switcheroo, Norman Bates is now a socially maladjusted underdog trying to go straight, and Lila Loomis (Vera Miles) is a vindictive prankster, still bitter about the murder of her sister twenty-two years ago – not without some justification, though for the purposes of this narrative, she’s undoubtedly wearing a black hat. At least that’s how I see things. I suspect how a viewer responds to Psycho II is largely dependent on their feelings about institutional rehabilitation, or perhaps preexisting opinions about the validity or possibility of forgiveness following murder.

The first film famously delayed introducing Perkins and Miles – top-billed in both movies – but the second is off like a starter’s pistol, establishing the central conflict in just two lines, spoken by characters off-screen, as the camera moves in on Perkins’ gangly frame seated in a courtroom:

Judge: Norman Bates is judged restored to sanity, and is ordered released forthwith-

Lila: What about his victims?!

The phrase “restored to sanity” is a howler in any context, but Anthony Perkins plays the part with an uncertain decency – every inch of him is consumed by twitchy trepidations and an eagerness to please – and the film around him has the good sense to make his reactions the most important factor. Yes, it seems that Norman Bates is our protagonist.

“When he murders again, you will be directly responsible!” Loomis yells at Norman’s psychiatrist, Dr. Raymond (Robert Loggia!), before storming out of the courtroom.

As I’ve said, this is a kind of haunted house story. But what’s doing the haunting is more insidious than any ghosts that might jump out at us, or even the remembered image of a twisted young man committing murder in the guise of his dead mother; Norman is a man-child who is fleeing his very memories, even as he returns to the place where they are most likely to recur.

Which is to say, coming home was probably always a bad idea for Norman Bates, but it’s easy to admire the character’s moxie – returning to the scene of his crimes confident that he can leave his traumas behind and start again. Or maybe he just has nowhere else to go. Perkins makes us feel every inch of this. It’s a damned impressive performance, and would be so even without the lingering shadows of his work in 1960.

“Damn cutbacks,” Dr. Raymond muses on Norman’s doorstep, lamenting the fact that there won’t be a social worker available to check on him. Would professional supervision on an outpatient basis have kept Norman out of the turmoil that comes to engulf him once more?

Norman starts work as a cook’s helper at a local diner, where he meets Mary (Meg Tilly). After she has an argument with her boyfriend, Norman offers her (creepily or collegially – take your pick) a room at his motel. Unfortunately, manager Warren Toomey (Dennis Franz, at peak sleaze) has turned the Bates Motel into what Norman adorably characterizes “an adult motel”, and all that that entails, so he promptly fires Toomey and offers Mary the guest room in his house. She accepts, though she does take some convincing.

“This is the first night I’ve spent in this house in years, much less along,” he tells her desperately. “A lot of my…troubles…had to do with this house. So, you see, I’m as scared as you are, just for different reasons.”

Apparently Perkins and Tilly didn’t get along too well on the set, but none of that shows. As the pair develops a platonic closeness, Norman begins to fall victim to some rather cruel pranks: someone’s dressing up as his mother, calling him and speaking in her voice, sending him notes, and generally undermining his newly-acquired sanity. Norman suspects Toomey, but Toomey disappears, and he’s not the type of guy people go looking for.

(Naturally “disappears” is code for “gets murdered”, but the audience is pretty much in the dark about the killer, assuming they’re willing to entertain the notion that it’s someone other than Mr. Norman Bates.)

For that matter, there are other unexplained disappearances. A pair of teens, apparently having wandered off from Camp Crystal Lake, sneaks into the basement of the Bates house to toke up and make out. Guess how that goes.

SPOILERS – PHASE TWO

Once Norman’s sanity starts to slip away, it’s revealed (to the audience, not to him) that Mary is actually the daughter of Lila Loomis, making her the niece of Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane. It seems that Mary and Lila have been partners in a gaslighting for the ages, actively undermining his state of mind, hoping that he’ll snap, attempt to murder someone, and get locked up again – this time for good.

Tom Holland’s script has the good sense to not waste a lot of time on Mary’s conflicted loyalties; as soon as the audience is privy to this plot, Mary’s had enough, and recognizes the monstrosity of her mother’s plan. More than that, her own feelings of guilt lead Mary to lie to the police, offering an unsolicited alibi for Norman during one of the murders. She becomes his de facto caregiver, trying to convince him that he doesn’t “have it in him – not anymore.”

But we’re not so sure. Some of his behavior towards Mary seems like an awkward and one-sided courtship. At other times, he becomes incensed with her, seemingly on the brink of violent rage, as when she won’t concede that he’s becoming increasingly erratic.

In the film’s most devastating moment, Norman weeps and confides to Mary that there are no more “good things” to remember about his mother (save the scent of phantom toasted cheese sandwiches) because the doctors “took them all away.” In lesser hands, this entire scene might seem a bit too precious, too staged, or too overtly “actorly” to be believed, but Perkins, Tilly and Goldsmith, with some invaluable help from Dean Cundey behind the camera, carry the day.

Psycho II is very much a product of its time, but it’s also home to some striking cinematic contradictions. The original was a cheeky, exploitative mindfuck made with peerless skill, shrill set pieces and very sharp humor. The sequel retains the humor, but it’s a much gentler piece of work; this in itself is strange, given the film’s thoroughbred slasher lineage and the ever more creatively sadistic trajectory that typified the genre at that time.

And although at first blush one might be tempted to lump it with the Nightmare on Elm Street sequels as yet another example of the “root for the killer” trend, we’re not cheering for Norman to commit murder so much as wanting to see him protected from the destructive bitterness of Lila Loomis. For her part, Loomis is killed in the basement, caught red-handed by someone dressed like Mother as she herself is getting ready to put on Mother’s wig to further torment Norman. No danger of missing that irony.

The story resolves itself with Mary dressing up as Mother in a misguided attempt to get Norman to behave himself. It backfires, with Mary accidentally knifing Dr. Raymond (about to catch her in the act of tormenting his patient). Visibly addled, Norman then heartbreakingly promises to take the blame for Mary/Mother just like he did last time. The cops are on their way though, having found Toomey’s car in the swamp, and as he tries to get Mary/Mother into the basement to hide, she stabs him several times.

It’s then that Mary sees Lila’s body under a pile of coal, and deduces that Norman was the killer all along. She raises the knife just as the police burst in and shoot her.

SPOILERS – PHASE THREE

Having been successfully gaslighted back into his mania, Norman kills exactly one person in Psycho II – the kindly, silver-haired Mrs. Spool, with whom he briefly worked at the local diner.

Emma Spool may be Norman’s biological mother (as is her claim), his aunt, his surrogate mother or none of the above. In any case, she seems to have some of the more bothersome Bates genes; in the kitchen, taking tea with Norman, she delicately confides that she, in fact, did away with all those nasty people. “When I saw what they were trying to do to my poor little boy, I couldn’t stand it,” she says with a tiny smile, “and one by one…”

This is my favorite kind of plot twist in a genre that is positively drunk with them – a mother ex machina, if you will. Five minutes earlier, the drama had effectively reached its conclusion, with the late Loomis ladies getting their wish: Norman has returned to his cinematic default setting, confident in the belief that his “real mother” is actually alive and well, calling him on the phone and bringing brutal justice to those who might wish her son harm.

Back at the courthouse, in a sly reversal of the original’s long-derided psychiatric exposition dump, Sheriff Hunt (Hugh Gillin) had laid out the improbable narrative for the district attorney’s staff. He was mostly wrong, of course, and when he saw that his listeners were incredulous, he pointed out that the sight of Mary Loomis in Norman’s mother’s uniform, standing over his huddled, wounded body and brandishing a knife, would’ve convinced anybody. “She’d gone mad,” he declares. “It was horrible.”

But then along comes Mrs. Spool to pay a visit, a timely reminder that no, Mary Loomis didn’t kill anyone (except poor Dr. Raymond). Neither did Lila, or Norman himself for that matter – at least not lately. Instead it was the polite old lady, the one who was so eager to reassure Norman on his first day of work: “I’m the one who encouraged Mr. Statler to give you the job,” she’d said. “I think it’s very Christian to forgive and forget, don’t you?”

Now she sips tea with Norman, and the mother and child reunion is only a motion away.

“After all,” Mrs. Spool continues, “you’re all I have in this world.”

Then this:

Norman carries Mrs. Spool’s corpse upstairs to his mother’s previously established perch at the window. “Make sure you don’t start playing with filthy girls again!” she chastises him, now sounding much more like the croaky and birdlike “Mother” that we remember.

We close on Norman’s silhouette looking down at us, and “Mother” looking down on him from her window, dusk settling in, an ominous Goldsmith sting playing us out.

Art, even if it’s somewhat lacking aesthetically, can change the way a person thinks and feels about important subjects. For me, seeing Psycho II at a young age opened up an avenue of empathy that might otherwise have remained closed – an awareness that rehabilitation is possible, that even the most monstrous crimes are committed by flesh-and-blood human beings, and that we lose sight of that at our peril.

But it would be the most scalding of hot takes to suggest that Psycho II is preferable to 1960’s Psycho in any way, shape or form (though it has its champions, Tarantino among them) and I wouldn’t stoop to that. I can admire how deftly it maneuvers the characters, the interesting business the script gives them, and the crafty way it returns our ostensible protagonist to the status quo. But what I find most endearing about Psycho II is its willingness to play with audience sympathies and expectations, and its commitment to replacing the lurid thrills of the original with a weary sadness, roman numerals in the title or no. In the end, Norman suffers the worst revenge imaginable – his madness prevails, which means we all lose.

Scattered Thoughts

- It bears repeating – Anthony Perkins gives a moving, nuanced performance here. But he is often hilarious too, particularly when he’s trying to be as normal as possible, as when he introduces his friend-who-happens-to-be-a-girl to his court ordered buddy: “This is Dr. Raymond. He was my psychiatrist in the institution.” This guy could teach Mr. Rogers a thing or two about open-faced earnestness.

- John Gavin, who played Sam Loomis in Psycho, died this week.

- I wonder if the folks at Universal deliberately waited until Hitchcock’s death to mount a sequel.

- Of the three characters who don mother’s outfit in Psycho II, none are Norman.

- Robert Bloch wrote his own version of Psycho II as a novel, and it’s quite the different animal.

- Director Richard Franklin would helm Cloak and Dagger the following year, which is interesting for a number of reasons: it stars little Henry Thomas, who would later play Norman in the flashback sequences of Mick Garris’s Psycho IV; it features John McIntire, whose booming voice and deeply craggy face were so memorable as Sheriff Chambers in Psycho; most remarkably, both Cloak and Dagger and Psycho II are concerned with characters who fabricate imaginary figures to cope with painful situations – namely the loss of their mothers.

- Psycho III was directed by Perkins himself, and it’s not bad either. Darker, more morbidly funny, filled with tips-of-the-hat to Hitchcock, and featuring a deliciously slimy turn by Jeff Fahey, it towers over most of the boilerplate slashers being made in 1986. But it’s definitely more willing to embrace the “slasher” designation, for better or for worse.

- One of the most impressive commenters on the old IMDb message boards went by the handle ecarle, and his erudite musings about the original Psycho are one of the chief things I miss about that place. I seem to remember him having mixed feelings about the sequel, mostly rooted in its softening of Norman’s character – not the “Mother” persona, but the young man himself, who is considerably seedier and more unlikeable in his original form. (If you happen to be reading this, ecarle, apologies if I’ve misrepresented or otherwise mangled your views.)

- Anthony Perkins and Robert Loggia share some very interesting scenes in this film. But they also have the distinction of starring in two of the most surreal breakfast food commercials ever broadcast. Here they are: