“How’re you gonna keep ‘em down on Crystal Lake after they’ve seen Manhattan?” quipped the studio exec.

Jason Goes to Hell is the ninth installment in the Friday the 13th series, and the first one produced by New Line Cinema. Paramount’s last stab, Jason Takes Manhattan, was generally regarded as a disappointment – a cinematic pricktease that dangled the promise of mass urban carnage in front of the audience before delivering a slow boat to Vancouver. The film had a terrific ad campaign, one so effective that box office returns were guaranteed, barring a very bad reception. How bad?

Here in Ontario the film was (somewhat inexplicably) slapped with a hard R-rating, which meant that nine-year-old me wasn’t getting in, no matter how persuasively dad argued my case to the dude in the ticket booth – and if blindly loyal dorks like me were kept out, what hope did the movie have?

No matter: As I would discover on VHS some months later, Jason Takes Manhattan is no one’s idea of a great slasher film.

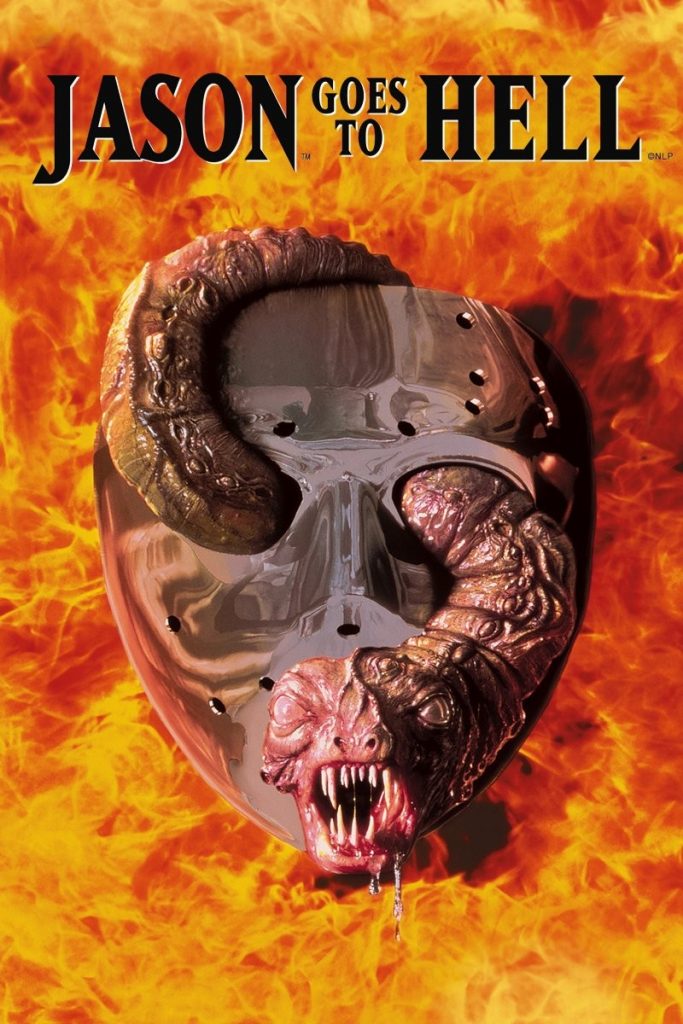

Four years later and it was the same scene again – me pouting while staring at a poster at the local multiplex. (Quite a poster, no?)

This was even more culturally significant than taking the character off the homestead; they were actually going to kill Jason Voorhees. Uh, like in The Final Chapter. But for real this time. Pinkie swear.

In any case, it’d been a long wait for more Jason – roughly analogous to the concurrent break between the Dalton and Brosnan Bond handoff – and the most pressing question (setting aside, “Are they really going to kill him this time?”): Could this franchise still produce a passably entertaining piece of schlock?

Yes and no, as it happens.

Jason Goes to Hell isn’t afraid to get crazy. For those of us who’d begun to bristle at the almost religious adherence to structural and story-based repetition of the series, there’s a lot of fun to be had here. The opening sequence generates a great deal of goodwill by gleefully subverting expectations. To wit, the obligatory babe in the woods (who dutifully baits the hook, stripping down for a shower immediately upon arriving at her cabin) is part of a sting operation to catch the undead killer. It’s wildly successful too, and a SWAT team unceremoniously guns him down – blows his ass up in fact. Heeding the Chicago wisdom of Malone, they brought a rocket launcher to a knife fight.

Anyway, Jason explodes, parts of him fly through the air, including the mask-sporting volleyball of scar tissue that is his head, and the still-beating heart.

As the SWAT bros give each other jubilant high-fives, a solitary black man in a cowboy hat watches from the shadows. “I don’t think so,” he murmurs.

So far, so good.

The premise that drives the next eighty minutes also gets points for…well, not originality; it’s mostly cribbed from better movies, like Jack Shoulder’s The Hidden, but at the very least it’s bold: Jason’s heart is so damned evil, that it physically leaps from person to person via the mouth, taking command of various bodies one at a time. First up is the coroner (the always-watchable Richard Gant, so righteous and so wounded on Deadwood) who, in a wonderfully off-putting piece of silent acting, warily glares at the heart atop the scale for a good thirty seconds before wolfing it down.

At any rate, following rules established by Cannon’s ninja films, only a Voorhees can kill a Voorhees, blah blah, so bespectacled, letterman-jacketed Steven (John D. LeMay, who’d previously played a different character on the Jason-free Friday the 13th TV series) goes on an extrajudicial mission to see that a member of this suddenly expansive family tree (which now includes his own daughter) can fulfill the film’s genetically-mandated mission. He alternately battles Jason’s different avatars, gets implicated in the murders himself, and rather nebbishily tries to protect his ex, Jessica (Kari Keegan), and their infant child.

This somewhat less-than-riveting Voorhees extended family drama continues apace, with Jason’s rancid heart changing chests every fifteen minutes or so. The most memorable body transference (and the series’ single most dafuq moment) involves a sheriff’s deputy being stripped naked, tied to a table with thick leather straps, then forcibly lathered up and shaved prior to ingress – all romantically bathed in the glow of a roaring fire place. This indignity isn’t enough apparently, as the deputy’s discarded body later dissolves into a goo-covered skeleton. Onward and upward, Jason.

Call me crazy, but as a primitive example of meta-genre filmmaking, I think there’s a lot to enjoy here. Steven Williams injects just the right kind of measured lunacy as bounty hunter Creighton Duke, the first scene’s skeptical observer, and a character so broad that the film can barely contain him. Everything he does is fascinating, from his bargain to provide information to our beleaguered hero in exchange for breaking one or two of his fingers, to his musing that the name “Jason Voorhees” makes him think of “a little girl in a pink dress sticking a hot dog through a doughnut.”

We’ve come a long way from dialogue like, “Hey Chrissie – how much further to the lake?” or “Camp Crystal Lake is jinxed.”

Also interesting is the way Jason Goes to Hell anticipates the indictments of media exploitation that drove the satirical engine of the following year’s Natural Born Killers (where American Casefile would become American Maniacs). Just as Robert Downey, Jr.’s Wayne Gale progressively becomes more directly complicit in the murders perpetrated by his subjects, Steven Culp’s Robert Campbell goes from being a generally unpleasant belt-and-suspenders sleaze merchant to a literal medium for Jason’s madness. As Jason’s shell, this guy is the recipient of more slow-mo bullet wounds than any character since Peckinpah sent Warren Oates to Mexico for the last time. Take that, A Current Affair.

The movie is cheeky in other ways too: the final moment of the film is too sassy to be casually spoiled here, but it hints toward the kind of self-awareness that would later drive the Scream franchise, and in view of subsequent films, has a surprising prescience; The Evil Dead’s book of the dead makes a brief appearance; Billy “Green” Bush drops by for a few minutes, then gets mistakenly stabbed with a ceremonial dagger; oh, and at one point, Jason’s essence or heart or whatever it is assumes the form of a baby skeksis-looking demon, darting up the checkered skirt of a previously murdered Voorhees-twice-removed to take control of her corpse.

These aren’t the modest and reliable pleasures of the earliest Friday films, but for a low-budget slasher film made a full decade after the genre’s heyday, you could do a lot worse. Director Adam Marcus may be a neophyte, but he maintains a brisk pace, and the stranger elements of the plot aren’t undermined by excessive jokiness; rather than scornful ofthe material, he largely seems content to tackle it head-on, without the comforting ironic distance of something like Snakes on a Plane.

One key element that doesn’t work at all is Harry Manfredini’s shrill, bombastic, entirely synth-based score, which lacks the low-key charm of his earlier work in quieter scenes, where it was as essential to creating a sense of the remote, isolated locale as the call of a loon across the lake.

Likewise, the attempts at Crystal Lake world-building are not entirely successful. Twin Peaks this ain’t, and the film’s attempts at establishing “local color” fall rather flat; there’s plenty of eccentricity, but it’s couched in exposition and performed with a community theatre commitment to scenery chewing. What I’ve always relished about the first few Friday the 13th films is the unflashy way they establish time and place, and how readily that helps to build atmosphere. The diner scene in the first film, for example, is populated with completely taciturn extras, who look all-but ready to fade into the wallpaper when an outsider asks about Camp Crystal Lake.

But even if this new approach to the townsfolk is too broad to be effective, it’s certainly never boring; hard to begrudge any film the opportunity to have Rusty Schwimmer explain the economics of shaping burger patties like Jason’s mask (the hole meat can be used in another burger) or allowing Steven Williams the chance to order “a side of Voorhees fingers.” Little touches like these are instrumental in moving the meter from “folly” to “proud folly.”

The masked killer would return in Jason X, which not only sends him into space, but also features a cameo by body-horror guru David Cronenberg. Occupying similar tonal real estate – not scary, sometimes audaciously high-concept, frequently amusing – the ninth and tenth installments of the series often feel like cinematic misadventures, but spare a moment to ponder the sequence of Jason’s travelogue: Manhattan, Hell, space. Is it any wonder the series has had such difficulty moving on? No more worlds to conquer.