“All the things that used to be inside me are outside me now. And so I can see all of the things inside you, Doctor. But inside of me is empty.”

On March 20, 1995, ten members of the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo released packages of nerve gas on the Tokyo subway line, in the deadliest act of terrorism in modern Japanese history. The cult, lead by former con man and self-declared messianic figure Shoko Asahara, blended elements of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, Hinduism, Yoga, apocalyptic Christian prophecy, the writings of Nostradamus, and even some ideas gleaned from science fiction to form an ideology built around igniting a third world war and purging the world of its sin in a nuclear armageddon. Aum Shinrikyo primarily targeted scientists and intellectuals for recruitment, and by the time of the subway attack, they had amassed over a billion dollars, had built compounds to manufacture and stockpile chemical weapons, and had plans of obtaining a nuclear bomb.

There’s something particularly unsettling about cults. We can wrap our minds around terrorism motivated by politics or profit. We can even wrap our minds around the random violence of a single madman. But how is it that one man can project his madness over an entire community? If these men claim divine or supernatural power, don’t they in some way demonstrate it when they can make others kill and die for them? How is it that so many people can drift so far from their rationality and humanity so easily? These stories shake our foundational knowledge. They make us question how fragile our attachment to our sanity is, how limited our understanding of reality.

In 1997, that social paranoia would form the basis of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s horror masterpiece, Cure. The film follows homicide detective Kenichi Takabe (Kôji Yakusho), whose wife Fumie (Anna Nakagawa) is suffering from mental illness. Fumie’s illness is handled with a light touch. She’s a beautiful, sweet, and patient woman, but she forgets things and sometimes she acts without reason. Takabe will return home from work to find the washing machine on with no clothes in it, or see that his wife has made him dinner, but forgotten to cook it. In one scene we see her walking to her psychiatrist’s office. She crosses a bridge and suddenly halfway across she forgets which direction she’s going. In a later scene Takabe comes home and finds the door open and Fumie missing. He searches for her in a mad panic, fearing she may have been kidnaped or killed, and finds her wandering the streets, having gone for groceries and forgotten the way home. Takabe loves his wife, but she’s becoming a burden. At times you can see the shadow of their old relationship, how much he relied on her for an escape from the horrors of his job, and the frustration she feels at no longer being able to be an active useful member of their marriage. Takabe is patient and understanding and he has begun reading psychology textbooks. This is a man who does not believe in problems beyond his capacity to understand and solve. Fumie is taking a more holistic approach. She is kind and patient and upbeat, feeling her way through a life that is often beyond understanding, trying not to be any more of a burden on anyone around her than she must. The first thing we see in the film is Fumie, meeting with her psychiatrist, and reading Bluebeard, a French folk tale about a man who murders several of his wives. This is an ominous selection.

The next thing we see is the first killing. A young man walks through a tunnel and breaks a large piece of pipe from the wall. He goes and meets a woman and they sleep together. The two seem happy together and comfortable with each other, but without warning and without emotion, the man takes the pipe and beats the woman to death before carving the letter X into her throat. He then goes to the shower to wash the blood off of himself. Kurosawa shoots the film mostly in long static takes, his camera pulled away from the action. We can see the characters’ body language, but not their faces. The camera does not react to the violence on screen, which is a chilling effect. It makes the violence feel unplanned, as though we are noticing something that the filmmakers have missed. It also gives the violence a detached, matter-of-fact-quality to it. Here are two people comfortable and content with each other, now one is killing the other, now here’s a person and some dead thing. One state of being is not presented any differently from another. There’s no special importance given to a human being. Nothing extraordinary about taking or losing a life.

Takabe is called in to investigate. He finds the killer cowering in a cabinet, naked and terrified. This is the latest in series of murders in which the victim’s body has been mutilated in the same way. In each case a killer has been caught and there is no doubt to their guilt. There is no connection between the killers. The details of the mutilations haven’t been released to the public. There are no books or movies that include this detail. The killers are unable to articulate why they did what they did, but Takabe’s colleague and closest friend, Dr Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), assures us that they are perfectly sane. Sometimes these things “just happen” he tells Takabe. “People like to think a crime has some meaning, but most of them don’t.” Takabe can’t accept this. He lives in a rational world where people do things for reasons, and actions can be understood.

Now we are on a beach. The ocean roars on the soundtrack. Two figures are very small, alone. The plot of the film progresses in this jarring way. We are thrown into situations with no bearings. Observing characters we don’t know, often doing mundane tasks. It’s a disorienting effect, depriving us of a point of view character for many of the most dangerous scenes. The stillness and the distance make us feel as though we are sharing the physical space with these characters. Since there is little editing or camera movement, the illusion of the screen as a “window” separating us from an immediately present reality isn’t challenged.

Here we are introduced to our villain, Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), and he enters in humble fashion. A wispy, wiry young man with a peach-fuzz mustache, he hardly seems capable of supporting the weight of his own body. He wears an oversized coat over an oversized sweater and even his hair seems too big for his head. He’s always half collapsed or teetering against a wall, drifting in and out of consciousness. His delivery is foggy and unfocused, his dialogue is noncommittal and runs in circles. He asks the other man on the beach, Tôru Hanaoka (Masahiro Toda), where they are, and when Tôru answers he asks, “where’s that?” When asked where he’s going, he responds, “Nowhere”. When asked who he is, he can’t remember.

Tôru takes pity on Mamiya, and brings him home with him. Tôru is an elementary school teacher, and you get the sense that he’s a pretty good one. He’s chatty, and a little goofy, a little excitable. He’s gentle with Mamiya, but he’s focused, pushing for practical information and keeping the conversation from drifting off track with the deft hand of someone who’s spent a lot of time talking to children. Tôru has a wife, Tomoko (Misayo Haruki), and if there’s a single skill I wish young directors would learn to develop, it’s how to stage multiple actors on screen at the same time. Haruki is only in the film for a matter of seconds, and yet we get a strong sense of her character, and the dynamic of this marriage. Tôru is bustling around the kitchen, and his wife enters. She’s wearing a nightgown, and is clearly tired, but helps him make a cup of tea that he’s fumbling with, as he moves to do something else. The space is small and cramped, but the two have an easy intimacy with each other. They move about each other in a natural intuitive way, with the awareness of each other that people have when they are in love. It’s quick, and the movie doesn’t draw our attention to it, but we like these people, and we have a sense of them as a generous, responsible, and loving young couple.

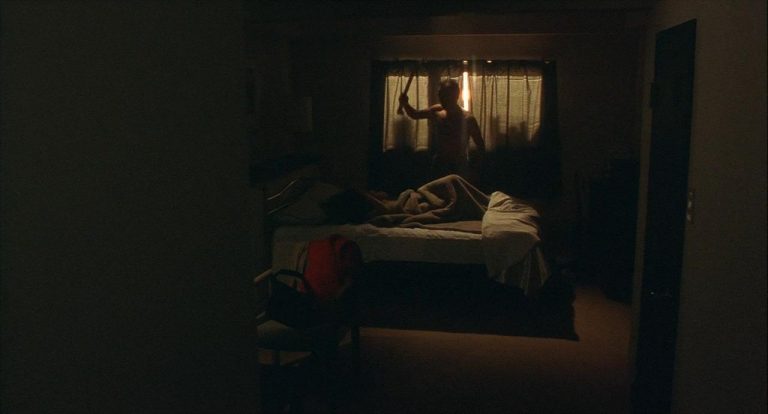

Tomoko goes to bed, and Tôru talks to Mamiya, trying to help the stranger regain his sense of himself. Mamiya for his part is fleeing the camera. He’s drifting out of the conversation, unwilling to answer anything, moving around the room generally making a mess, and pushing Tôru to talk more about himself. Mamiya seems unthreatening, ineffectual, and not entirely conscious of his actions. But in truth he’s carefully setting a trap for his host, and when he draws his lighter he suddenly becomes controlled and attentive. The film begins cutting in closeups here, and the effect is unsettling. A break in the natural rhythm, as the director suddenly imposes his will over ours, commanding our focus in a way that he hasn’t before. This time we don’t see the full process of Mamiya’s hypnotism. Kurosawa will tease that out over the course of the movie, but in the morning Tomoko has been murdered and Tôru is suicidal.

Once again all that Detective Takabe can do is bear witness to the carnage. He asks why Tôru did it. Was it a film, a novel, did he hate his wife? Tôru tells him that “there was no reason,” that, “At the time, it seemed like the natural thing to do.”

The film follows this pattern for a while. Mamiya infects a victim, Takabe investigates the aftermath. This is where Kurosawa’s slow, static camera work pays the highest dividends. Characters are often placed at extreme ends of the frame, so that we have to dart back and forth, choosing what to watch and who to pay attention to. Mamiya is often passive, and yet there’s a clear methodology to what he’s doing and a purpose to his movements. But we can’t quite grasp all of it. We want to watch him to understand how it works, but that also means giving ourselves over to the spell. The quiet and the simplicity of the movie give it a sense of authenticity and physical reality that is usually absent in stories of the supernatural. A sense that our souls and our sanity are also on the line.

The conversations themselves are interesting as well. The way Mamiya draws out the darker nature of his victims, and the way the killers struggle to explain why they acted. Kurosawa also makes an interesting choice by selecting as his murders; a young, happily married elementary school teacher, a young pretty doctor, and an amiable middle-aged cop. The violence does not come from the fringes of society, but from its pillars. From people who we expect to be nurturing and protective. And it is inflicted in an intimate way; on lovers, wives, and partners.

The film also makes a smart decision by having Takabe (hesitantly) pitch the hypnotist theory to Sakuma before he’s really gotten all the pieces to put it together… and having Sakuma shoot it down as scientifically impossible. This does two things. First it allows Takabe to seem like a skilled, intelligent detective, reaching the truth faster than we expect him to, and not spending the whole film behind the audience. Second, it places Mamiya squarely in the realm of the supernatural. Whatever he is doing, it’s something mystical, something beyond rational explanation. And when Takabe finally finds him, he’s able to accept the magnitude of the threat without the movie having to do a lot of leg work to get him there.

The two paths eventually collide, and Takabe interrogates Mamiya. Mamiya is not an X-Man who can control minds at will. There is a technique to what he is doing and if that technique is interrupted, he won’t be successful. But although we are aware of this technique, we don’t understand it. We know more than Takabe does, we can sense danger in places that he can’t, but we’re never sure which parts are necessary and which are incidental. This creates an incredible amount of tension in these scenes because we’re never sure who has the upper hand, and the dynamic of a scene can change on a dime. Mamiya is able to get under our skin in the same way he does the rest of his victims.

Takabe responds to Mamiya differently than the others. He’s hostile. He’s skeptical of Mamiya’s amnesia. When the younger man tries to evade his questions, he pushes harder. When he tries to turn the subject to Takabe, he’s guarded and evasive himself. When he tries to draw his lighter, Takabe slaps it across the room. Most horror movies are, whether intentionally or not, essentially morality tales. There are traits that lead our characters to doom (say, promiscuity in ‘80s slashers, or curiosity in Universal’s monsters), and traits that save them. Here both the film and it’s villain are pushing us in the same direction. Mamiya’s mysticism turns his audience into sociopaths, but at the same time, the characters who fall victim to him do so because they treat him with empathy and pity. Mamiya attacks our humanity, and Takabe evades him by shutting his own humanity down. “Who are you?”, Mamiya asks.“A detective.” Takabe responds, no personal identity, only the function of his job.

At the same time Takabe is much more emotional in their meetings than the others were. He loses his temper, throws the other man around, threatens him, shouts at him. When Mamiya finally draws out his frustration with his wife, he all but breaks down. “I know my wife’s a burden! You don’t need to tell me that!” before turning it back on Mamiya, “Her I can forgive. It’s you I can’t.” Takabe is aware of the darker parts of his nature. He’s made peace with himself, and so he is not as easily manipulated.

Still, Mamiya is having an effect. Takabe hallucinates his wife’s death, and decides to check her into a mental hospital. At least somebody in this marriage needs to be in touch with their sanity. He visits Sakuma and finds he’s also been talking to Mamiya.

Later, he finds his friend has handcuffed himself to a pipe and killed himself. Sakuma’s suicide complicates the morality of the story. It’s possible to, if not to entirely resist Mamiya’s influence, than at least not to give into it completely. Sakuma would rather die than commit murder, but the others would not. Mamiya is not simply imposing his own evil in place of his victims’ will, but drawing out something dark and cruel that was always a part of them.

Mamiya escapes from prison and Takabe finds him at a deserted, mystic place that we visited earlier in the investigation. Mamiya has become fascinated by Takabe, and believes they process, if not the same power, than the same potential, a spiritual kinship. He begins to talk to Takabe, to explain his nature, and the detective abruptly shoots him. It’s a refreshingly clear-headed, direct moral action. Mamiya is too dangerous to live, and there won’t be any hand wringing over what moral lines can’t be crossed, or if killing turns heroes to villains, or any of the usual nonsense. Takabe understands what needs to be done, and does it. As Mamiya dies he moves his hands in an X as though casting one last spell over Takabe, but he’s interrupted by another bullet.

We flash to the mental hospital where Fumie’s being held and see a brief shot of a woman with an X carved in her throat. It’s too quick to be sure if it was Fumie, or even if it’s meant to be literal, or simply another vision.

Takabe is in a diner we’ve seen him in before. He seems relaxed now in a way he hasn’t been before. He says something to the waitress. In a slow, static, wide shot we watch her walk back behind the counter and pick up a knife. Did Mamiya set up more violence before he died? Has killing him released his evil like a contagion across the public? Did his final spell work, and is Takabe now carrying on in his place? I don’t know. The only thing that matters is that we can no longer see a waitress pick up a knife without anticipating a vicious murder. The bonds of trust that hold society together have been ruptured. All that’s left is carnage and despair.

This July, Shoko Asahara, along with twelve other cult members involved in the Tokyo subway attack were finally executed. Aum Shinrikyo itself is still around, though it’s fractured and rebranded. The remaining branches have publicly denounced the violent methods of their predecessors, though they continue to be monitored as a terrorist organization.

Will you sleep easy tonight, now that Asahara is dead? Do you think there is less evil in the world, or simply less people?