Losing a kingdom is a pain only matched in intensity by the thrill of gaining it in the first place. Coming late in his career – Chaplin would only direct one other film after this one and star in none others – A King in New York lacks the perfectionism and technical prowess of his earlier work. The politics on its sleeves and Chaplin’s character give the impression that it’s a bitter rebuke of a country that failed to appreciate him as kind figure of Hollywood royalty. Not that this country had the opportunity to receive the rebuke; Chaplin didn’t even bother to distribute the film in the United States where he was the subject of derision and boycotts at the time.

King certainly has notes of scorn for American society, but bitter it is not. Miffed? For sure. Chaplin is a correcting parent here, not a scold. And in its final gesture, A King in New York is more confident in the director’s voice as a satirist than his masterpiece of satire The Great Dictator.

A King in New York consists of two parts each with its own target. The first part is a longer and funnier, if more nonsensical, take on American popular culture in 1957 including celebrity worship and the rise of television’s influence. The second part, mercifully shorter in the cut available in the United States, concerns the anti-communist persecutions of the 1950s.

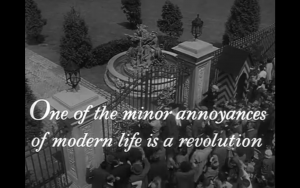

King Igor Shahdov (Chaplin) escapes revolution in his home country of Estrovia for the Ritz-Carlton in Manhattan. His palace and, more to the point, the treasury, has been emptied. This would seem to set up a film about a scheming despot bound for comeuppance and redemption in the righteous city of New York. But from the start, it’s the opposite. The noble and misunderstood Shahdov is frequently at the mercy of a confusing, misguided and – most horrifying – gauche public in the US’s supposed greatest city.

A parody of a rock concert – including teens daring to dance in the center aisle before taking their seats at the proper time and the musicians rocking out on instruments more suited to a jazz combo – play as the grumblings of an old man who doesn’t quite understand the obsession with this new-fangled noise (though it’s partially redeemed by a shot of Chaplin gingerly stepping over several fainted young women). But this is immediately followed by a trio of hilarious movie trailer parodies that show Chaplin’s satire retains its edge when he’s familiar with the topic. The King and his Prime Minister (Jerry Desmonde) walk out of the theater in favor of a quiet restaurant. “Ah, this is agreeable. Not so noisy,” comes a telling line from the master of silent cinema. This setting, too, devolves into comedic din.

Chaplin’s King Shahdov, while not always quite in control of his circumstances, is ever the noble victim. The money he took for safe-keeping from Estrovia’s treasury is stolen, leaving him penniless. He is going through a divorce from the Queen, but an amicable one and for her benefit. His aristocratic airs contrast with the boorish Americans who sport various accents from Bronx-ish to vaguely Southern as they pander for autographs (on a Kleenex, in one case).

Chaplin’s King Shahdov, while not always quite in control of his circumstances, is ever the noble victim. The money he took for safe-keeping from Estrovia’s treasury is stolen, leaving him penniless. He is going through a divorce from the Queen, but an amicable one and for her benefit. His aristocratic airs contrast with the boorish Americans who sport various accents from Bronx-ish to vaguely Southern as they pander for autographs (on a Kleenex, in one case).

Shahdov is a king among subjects, even in his country of exile, and it’s only after bouncing off this conceit that any of Chaplin’s satire gets directed at himself. The king is proud, but money needs force him to sell out and appear in a series of television endorsements for cold, hard cash (there’s a funny moment when Chaplin is told the “letter” he’s tearing up in anger is a check for ten thousand dollars, and a sudden wash of regret briefly replaces his regal indignation).

Also in the category of self-parody: a verbose lad named Rupert Macabee lectures the king endlessly about the meaning of freedom and the benefits of anarchy. Many reviewers find Rupert irritating (which he is) and a cipher for serious points the director wants to include (which he is not). He’s actually a satire of political moralizers and lecturers, probably including Chaplin (young Rupert is played by Chaplin’s son Michael).

One could charitably read Shahdov’s pursuit of “TV Specialist” Anne Kay (Dawn Addams) as a spoof of Chaplin’s own controversial pursuits of younger women. But as their screentime begins with a disturbing bit involving a bath and a keyhole and later involves a wrestling match over a stolen kiss, the relationship at best plays with the audience’s expectations of a beautiful romantic foil and at worst suggests a lecher at the production’s wheel. To the film’s credit, King Shahdov ends up reconciling with his queen rather than winning the hand of the nubile Kay. Kay is given a large amount of agency as a woman in an entertainment profession and Addams’s scene of performing product-placement ads to hidden cameras shows off substantial comedic chops.

One could charitably read Shahdov’s pursuit of “TV Specialist” Anne Kay (Dawn Addams) as a spoof of Chaplin’s own controversial pursuits of younger women. But as their screentime begins with a disturbing bit involving a bath and a keyhole and later involves a wrestling match over a stolen kiss, the relationship at best plays with the audience’s expectations of a beautiful romantic foil and at worst suggests a lecher at the production’s wheel. To the film’s credit, King Shahdov ends up reconciling with his queen rather than winning the hand of the nubile Kay. Kay is given a large amount of agency as a woman in an entertainment profession and Addams’s scene of performing product-placement ads to hidden cameras shows off substantial comedic chops.

This front half, with jokes about facelifts and televisions in the bathroom (complete with a windshield wiper to keep it clear) has a prescience that extends to today. The commercials, where he endorses a product simply by using it on-camera, haven’t changed a bit in the era of celebrity twitter. In one case, he gives an ironic non-endorsement that nonetheless grabs the public’s attention in a live-broadcast version of a viral video. If anything, the film is too light on these subjects, treating them as the realm of fallen kings. That other 1957 film about television, A Face in the Crowd, predicted how the young medium would become a kingmaker.

The tedious second half swaps out these concerns for a statement on McCarthyism by way of Chaplin’s first feature success, The Kid. The young Rupert is taken in by King Shahdov while his parents stand accused of being Communists. Shahdov is then accused of communist sympathies by an overblown TV news report and must appear in front of a HUAC-like committee. Through a series of slapstick bits, Shahdov ends up spraying the whole committee with a firehose.

Here’s where the film gets interesting again, when it drops interest in the anti-communism theme almost as quickly as the pop culture observations of the first half. Unlike the real-life Chaplin, Shahdov is exonerated immediately. Rupert fares worse, turning in his parents’ friends under the threat of losing his parents. Shahdov comforts the boy before departing back across the Atlantic.

Here’s where the film gets interesting again, when it drops interest in the anti-communism theme almost as quickly as the pop culture observations of the first half. Unlike the real-life Chaplin, Shahdov is exonerated immediately. Rupert fares worse, turning in his parents’ friends under the threat of losing his parents. Shahdov comforts the boy before departing back across the Atlantic.

By the time the film ends with a European “Finis,” the McCarthyism is shrugged off. It’s as ephemeral as the television spots and loud music of the first half. Shahdov says he’ll wait for the insanity to blow over in Europe. This isn’t as bold a stance as Chaplin made against Hitler in The Great Dictator in 1940. By 1957 HUAC was in decline. Joseph McCarthy himself was censured by the Senate three years prior.

Contrast the handling of final political statements in The Great Dictator and this film. The Great Dictator, which Chaplin gestated with his usual care over the course of two years, ends abruptly with an endless out-of-character monologue imploring world leaders for peace. A King in New York, running on a tighter budget and schedule than Chaplin had ever had for a feature, ends with a near-shrug. “This madness won’t go on forever,” Shahdov assures Rupert. “There’s no reason for despair.”

Chaplin’s grudges are on display, for sure. His subjects for satire (culture in general and motion pictures in particular, aggressive reporters, HUAC) all double as personal gripes, and Chaplin can’t give up his pedestal. But if Chaplin had lost the time and ability to craft scenes with the precision of The Great Dictator or The Gold Rush, his instinctual moves forward through a shorter production schedule reveals that his mastery of pathos that keeps even this lesser film relevant.

A King in New York is a wounded man’s assertion that America will nonetheless overcome its own worst tendencies. After everything, Chaplin finds this truth so inevitable he doesn’t feel the need to underline it.