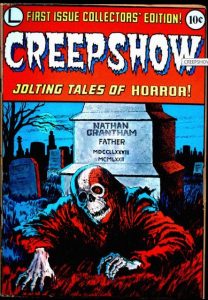

Horror, as it befits the genre, is never truly dead. It has moments of critical celebration and drubbings, but even when it’s shambling along half-dead, coasting on the fumes of overused trends and tricks, it’s still, in fact, there, just waiting for a spark to jolt some life back into its body. Less reliable within the genre, but ultimately always around, is the horror anthology. The various EC horror titles ruled the 1950s, and their destruction at the hands of Fredric Wertham is the reason superhero comics are the cultural juggernaut they are today. Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror and Mario Bava’s Black Sabbath were major touchstones of the 1960s, and Freddie Francis’s Tales from the Crypt kept it going through the very sparse ’70s. In his excellent nonfiction book On Writing, Stephen King makes it clear that he owes a huge debt to these forebears, elaborating about one tale where he novelized a Corman production of The Pit and the Pendulum to sell at school and wound up with his first bestseller. (Until the point where he got caught by school officials and had to refund everyone their money and take back his stapled photocopies.) While King’s work is littered with references and allusions to these works and others like it, he had yet to do a full-blown homage until Creepshow.

The film, written by King and directed by George A. Romero, is presented as stories in a comic book (called “Creepshow”), part of a wraparound segment about a kid (Joe Hill, Stephen’s son and novelist in his own right) with an abusive step-father. One stormy night the step-father, who believes comic books are a poor, trashy excuse for entertainment, throws the titular comic in the trash. A violent wind blows the comic out of the trash, and around the cul-de-sac of the neighborhood, occasionally flipping pages to new stories. By morning the comic is picked up by a pair of trash collectors, who note that someone has already sent away for a voodoo doll. The film ends with the boy repeatedly stabbing his very own mail-order voodoo doll, as his father painfully dies at the kitchen table.

Because of this framing device Creepshow is a literal Comic Book Movie. Even though it isn’t based on any pre-existing comics, King and Romero do an incredible job of recreating the essence of this pop culture period. King’s stories (6 in total, if you count the wraparound segment) capture the borderline nihilism that defined the EC horror comics. Characters often die for moral transgressions, but it’s equally likely for characters to be killed for no real reason, because the world is dark and full of terrors. In “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill,” the titular Jordy (played by King) touches a meteorite that crashed onto his property and slowly turns into plant matter, while the meteorite sends spores into the air and colonizes an ever-expanding radius around itself. This is an alien invasion without thought or consciousness or even a central nervous system. It’s just deadly plants from outer space that won’t stop growing.

While King nails the tone, Romero’s directorial vision brings home the feel of reading a comic. In “Father’s Day” there’s a scene with multiple panels on screen, each showing an evocative angle on a different scene, and Romero guides your eye in the proper sequence through a seamless flow of action. In many cases, especially when a character screams in terror, Romero’s cinematographer and VFX department kick things into high gear, replacing the background with stylized action lines and bathing the scene in high contrast red and blue lighting. The result is the kind of eye-popping work that turned the limitations of the four-color printing process into a bold and distinctive style. Occasionally the frames around images are more expressive than white gutters, such as the cockroach border that surrounds a close up of a man’s eyes in “They’re Creeping Up On You,” or the ragged red edge that frames the expositional flashback at the start of “Father’s Day.”

Most importantly, for the comic book featured in the movie Romero got veteran comic book artist Jack Kamen to provide illustrations for the prop book. Kamen, of course, was an illustrator on many of those EC titles, and his compositions glimpsed briefly at the beginning and end of each segment lend an air of authenticity to the film.

Now, just because King and Romero do such a great job of evoking these old comics they aren’t slavish to every detail. Most significant is the silence of the film’s “host,” The Creep. While the comic within the movie is filled with the kind of punny purple prose introductions that would become a trademark of HBO’s Tales from the Crypt, The Creep here is silent, and there is no narration in any of the stories. This makes the stories feel less ironic, brings the horror more to the fore, and highlights the bleakness at their heart. Not that the stories are without humor (“The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill” and “The Crate” in particular have some inspired moments of dark comedy), but Romero and King want to maximize the horror.

Creepshow is a stone-cold classic, with a distinctive visual aesthetic, incredible special effects, and a bunch of really unsettling scares. It gave a significant boost to the horror anthology, producing a sequel and immediately inspiring Tales from the Darkside (both film and TV series) as well as HBO’s Tales From The Crypt. The film was even turned into an anthology series of its own on the streaming service Shudder, employing many of the same techniques on display here. As for Stephen King… well, there are some who say he’s still out there, writing scary stories. Some folks even say that, sometimes, he writes comic books. But that’s only what folks say, right?