One of the beautiful things about poetry is its ability to evoke great understanding and empathy with very little detail. We don’t need the particulars of why the Grinch hates Christmas, we only need to know that it grates on his every nerve and he just wants to shut it all down. We don’t have to understand, we just have to empathize, and at one point or another, for an incalculable number of reasons, we’ve all not wanted to deal with the jolliest holiday in the history of contemporary culture. For all of Dr. Seuss’s complicated meter and imaginative vocabulary, it’s a simple, relatable sentiment perfectly conveyed.

One of the beautiful things about animation is its ability to create a totally convincing world. Special effects, prosthetics, or CGI in a live action movie can often feel removed from everything around them, and even the best of them have moments where you find yourself appreciating the craft rather than believing in the story. With the exception of stylistic choices, everything in animation is on the same plane of reality, and everything that happens just happens. You don’t need trick photography in order for Wile E. Coyote be crushed by a rock, you just draw it.

The most complicated thing about adaptation is there is no one right way to adapt something from one medium to another. Everything from slaving devotion (Kenneth Branagh’s 4 hour, unabridged Hamlet) to wild reinvention (10 Things I Hate About You) and everything in between is an equally valid approach, and you’ll never really know if you’ve found the right approach until after the work is done. And while Chuck Jones’s 1966 adaptation doesn’t add any dialogue or story (besides a few songs written by Seuss), it lets the story out considerably to accommodate motion and physical gags.

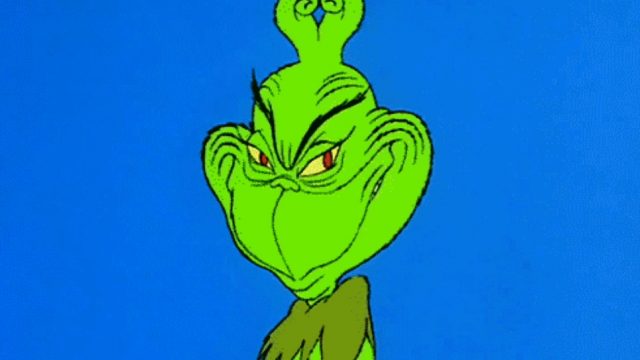

There’s plenty of character in Dr. Seuss’s original illustrations, but Jones breathes life into The Grinch and Max and the various Whos. When we see the Grinch looking down on Whoville with disdain he spins his head around when the Narrator says it might not be screwed on quite right, and pulls in an X-ray screen over his chest when the same Narrator reveals that the Grinch’s heart is 2 sizes too small. Max is full of puppyish energy and unbridled enthusiasm as he observes the same Christmas traditions that the Grinch despises. He expands on scenes that passed by in a few sentences on the page with expert comic set pieces. There’s the sequence of the Grinch assembling his Santa suit and sleigh, taking measurements and sewing cloth as Max is used as a dressing dummy and gets caught in a sewing machine. The race down to Whoville, where Max finds himself routinely out-paced by the massive sleigh he’s pulling. One of the funniest animation moments is the Grinch freeing himself from the tightly clinging Max latched onto his head, pushing him down his body and around his ankles. The entire Christmas-napping sequence, where the Grinch plays billiards with ornaments and sets up trains to travel down tracks and into his sacks. And all throughout there’s the Grinch’s incredibly expressive face, doing more with a sideways glance than most actors can do in an entire monologue. It’s top notch animation filling in the gutters around a top-notch poem.