It’s strange to think of The Walt Disney Company as an entity intimately familiar with failure, yet even a casual perusal of its history reveals everything from a surprising number of box office flops to the constant threat of shutting down entire divisions of the company. It’s easy to forget how often Disney runs into financial trouble, especially when they spend billions acquiring other companies, but it’s something that happens with a surprising amount of regularity. As a matter of fact, with the closure of their theme parks all around the world due to COVID-19, they’ve reported a loss of 5 billion dollars.

The situation in 1960 wasn’t quite so dire as all that, but feature animation was in serious danger of being scrapped due to both the commercial failure of Sleeping Beauty (1959), rising animation costs and Walt’s lack of enthusiasm for the medium (diverted by an interest in television, live action film, and his theme park). Needing to cut production cost, the animation department made a major decision that would define the look of Disney feature animation for decades to come.

Credit for the innovation belongs to two men: Ub Iwerks (the original Disney animator) and Ken Anderson (an art director for the studio). Ub Iwerks had been experimenting with using Xerox cameras to transfer drawings directly onto cells, and by 1959 Xerox had made photocopier machines commercially available. With the process more refined, Ken Anderson suggested to Walt Disney that they could print cels using photocopiers and cut out the inking department. The result was not as clean as the tracing process, resulting in a very sketchy look, but the animators loved it because it meant they could see more of their actual work up on the screen. And so began what was affectionately known as The Xerox Era.

Incidentally, the film also marked the end of an era, as it would be the the final film of veteran animator Marc Davis. One of the legendary Nine Old Men, who represented the core of Disney’s animation team, Marc’s career stretched back to the very first Disney feature, Snow White. A strong draftsman with a steady hand, while Marc animated a variety of characters he was most often given the beautiful, difficult-to-animate, and not-always fun leads, including Cinderella (Cinderella [1950]), Alice (Alice in Wonderland [1951]), Tinker Bell (Peter Pan [1953]) and Aurora (Sleeping Beauty [1959]).

With that in mind, his final creation, Cruella de Vil, was a welcome depature. “I think I enjoyed working on Cruella more than any of the others – she was the broadest thing I ever had a chance to do, and I enjoyed that aspect of her. She also operated without magic, unlike characters in Sleeping Beauty, Alice, or Cinderella. She was just a nutty woman. She’d come in and go out and leave havoc wherever she went, and had no idea that the killing of these little puppies for a coat involved pain and suffering. She’s pure evil, and that’s what makes her interesting.” (Marc Davis In His Own Words – Imagineering the Disney Theme Parks, page 12). Davis animated nearly every frame of the legendary villain.

Marc didn’t leave Disney Animation because he didn’t think he was getting enough interesting work. He didn’t really leave at all, Walt just moved him over to WED Enterprises (the company today known as Imagineering). To step back a bit: when Walt was building Disneyland, he liked to use all of the talented people who worked for him, and so a good number of artists from the studio wound up designing and building the park. Marc wasn’t involved in the initial design, but Walt did hire him to do some plus-up work on the attractions Nature’s Wonderland and The Submarine Voyage in the mind-fifties. Because, as we all know, Disneyland is never truly finished. WIth the park reliably turning a profit by 1960, Walt decided to really see what he could do in this new medium, and so he hired Marc as one of his lead draftsmen. Marc Davis was working at WED full time by 1961, though he didn’t formally resign from Animation until 1962.

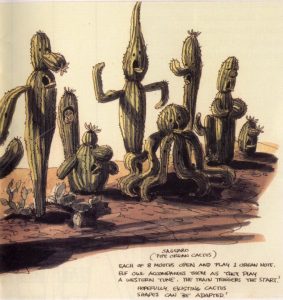

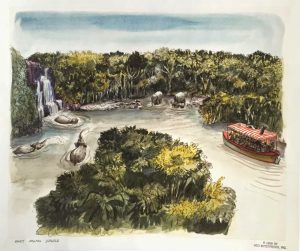

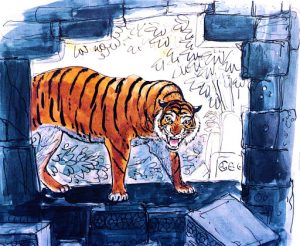

Davis would go on to design characters and develop a number of legendary Disney attractions, including Pirates of the Caribbean, The Haunted Mansion, and the Country Bear Jamboree, and while nothing he designed actually materialized in the park in 1961, there was many pieces of concept art from that year, including plus-ups for The Jungle Cruise, the New Orleans Square expansion, as well as the Enchanted Tiki Room. There are also multiple sketches for Pirates of the Caribbean dated 1961, but they are for the iteration conceived of as a walk-through wax museum, and most of those concepts wouldn’t make it to the boat ride.

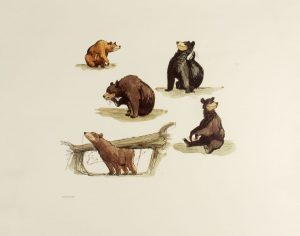

Among Marc’s many contributions to The Jungle Cruise were a number of animal encounters, including the famous elephant bathing pool. A lot of what he did was scenic redesign, with some realistic and interesting animal tableaus, but his greatest contribution was the gag involving the expedition party treed by an angry rhinoceros. (They were warned, and they’ll get the point in the end)

Development on The Enchanted Tiki Room stretched well into 1962, but here you can see a macaw and toucan exploration done by Marc in ’61.

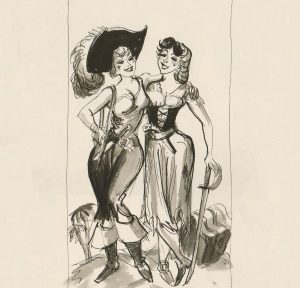

The early concept of Pirates of the Caribbean was to be a walk-through wax museum, and early in that development Marc had the idea that they would include scenes of historical pirates. Here you can see some sketches for Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Even within 1961 the project would start gravitating more toward the romantic idea of pirates than any specific real ones.

That about does it for 1961 and Marc Davis. It was a year of tremendous change for the man, technically working in two departments, but taking steps to completely transform his career. It’s a wild journey still ahead for him, and if PA school doesn’t kill me I might just come back and tell some more of it.

If you like art, consider giving me a dollar a month on my Patreon.