If you ask me if I’ve ever lied in my role as a parent, I’d answer that I have maybe a couple of times. And I’d deliver this answer with a straight face because I’ve become such a practiced liar in my seven years as a dad that I don’t always recognize when I’m doing it.

There’s generally two categories of lies: internal and external. The internal are the fibs told to my children. Subjects include Santa Claus, my fondness for certain members of the extended family, particulars about the very real dangers in their own neighborhood and the fallibility of adults in authority. The true details of these things will emerge as they mature. For the time being, they need to know enough to experience the world without undue fear while still thwarting the things that make the world such a frightening place in reality. These lies set parameters for their own benefit and safety. I hope.

I confess this in a cold sweat because I’m not getting the benefit of the second category of parental lies, the ones told to the outside world about the inner workings of one’s family. “Lies” is a strong term for some of the exaggerations and elisions in this category which may include accounts of their weekly television intake or details of my fatherly bragging. When I’m talking about my daughter’s interests, of course I’m playing up the week she got really into the science kit, downplaying how many songs about poop and pee she’s taught her brother (though some are quite creative!)

This latter category of lies is one of about fifty gut-twisting elements in Bobcat Goldthwait’s dark dramedy World’s Greatest Dad. Lance (Robin Williams) is the single father of Kyle (Daryl Sabara). A failed writer, Lance teaches English at Kyle’s school where he keeps tabs on his son’s academic and disciplinary problems, dates another teacher named Claire (Alexie Gilmore) and quietly seethes in jealousy when colleague Mike (Henry Simmons) gets a piece published in the New Yorker. One night he returns home to discover Kyle dead of an autoerotic asphyxiation accident. He stages a suicide complete with a note. When the note is published in the most gung-ho of student newspapers, Kyle becomes a tragic and popular figure among the student body. Lance follows up by writing and distributing a fake journal purportedly by Kyle and finds himself suddenly courted by talk shows and publishers.

This is a cauldron of dark, dark brew and the performances by Williams and Sabara take the movie into deeply uncomfortable places even before tragedy strikes. Lance gains our sympathy with his circumstances, but he’s also a sad sack living a paternal nightmare of ineffectiveness. His fear of loneliness makes his every olive branch to Kyle look like a desperate white flag. Sabara plays Kyle as not just a callow shithead, but as someone with deep behavioral problems that Lance is unequipped to handle. Kyle is unceasingly rude to everyone in Lance’s life and particularly vile to Lance himself, calling him a “fag” and taking advantage of any inch of kindness. When Kyle complains ungratefully about the new computer monitor Lance has given him (the same monitor he’ll be discovered dead in front of) you feel how Lance has taken up residence at the breaking point. It’s no wonder he can only muster a fatherly lie once Kyle is no longer around.

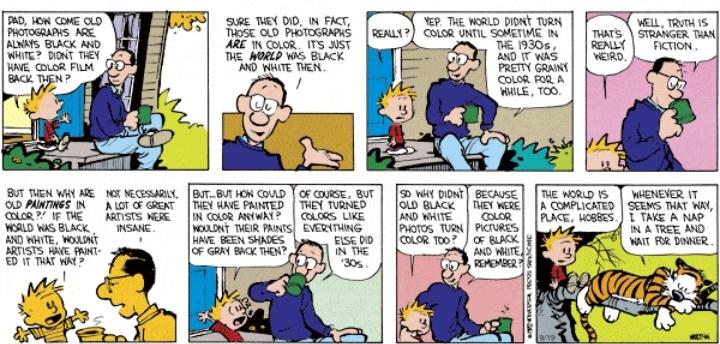

For the extremity in internal lies, we turn to Yorgos Lanthimos’s Dogtooth. The father in Dogtooth (Christos Stergioglou, credited as “Father”) keeps his children sequestered in a compound where, among many other disturbing things, they are taught the wrong definitions of words, told that cats are the most dangerous animals known to man and believe they’re listening to their grandfather sing when Father plays a Frank Sinatra record. The twenty-year-old son (Hristos Passalis, credited as “Son”) has scheduled trysts with Christina (Anna Kalaitzidou) who is paid by Father to take care of his sexual needs with less passion than the average trip to the dentist. This is the less alarming of Father’s sex-related solutions. It’s an uncanny, often disturbing movie, though at its lightest, Dogtooth resembles the occasional Calvin & Hobbes cartoon where Calvin’s dad (credited as “Calvin’s Dad”) can’t resist messing with Calvin and his limited worldview.

Both films, like any strong satire, create an outlandish scenarios with unsettlingly familiar contours. Lance’s fake journal entries give his own musings the attention and adoration of all the people that previously ignored him, a father living vicariously through his child. Dogtooth’s Father controls as a habit, preserving a set of eccentricities by imbuing his offspring with them – a long, unchecked invocation of “because I said so.”

Neither bad dad can sustain the illusion indefinitely. From Christina, the elder daughter (Angeliki Papoulia) gains possession of a couple movies from the outside world and reenacts them incessantly. Eventually she hides in the trunk of her father’s car. After a fruitless search, Father takes the car to work the next day. It’s never shown if his daughter escapes to freedom or simply finds herself trapped in a smaller prison in the outside world. Lance, by contrast, finds freedom in confession, shedding the lie, his false friends and his clothes.

And so it is that the lies of fathers come to light eventually. What remains after the collapse will be the motivation behind the half-truths, subterfuges and omissions. Luckily, my lies aren’t so self-serving as Lance’s and my children won’t remember my house rules as growth-stunting inanity. That’s what I tell myself. But then again, I’m obviously not to be trusted.