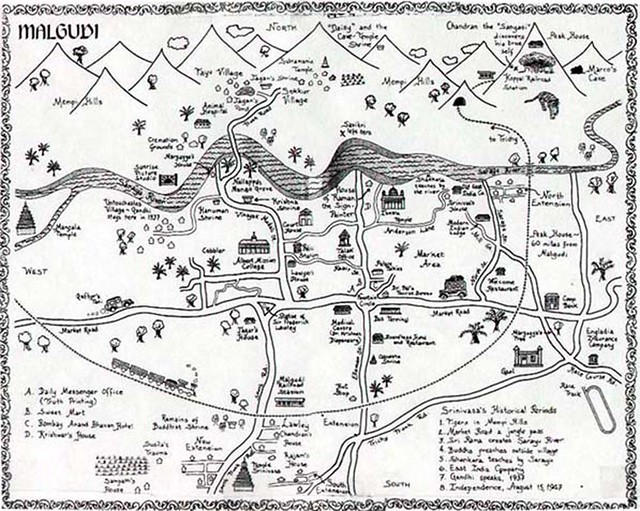

At first glance, breaking into R.K. Narayan’s Malgudi series can seem daunting: the author set fourteen of his novels and as many short stories in that fictional town, reflecting a lifetime of work from the 1930s to the early 90s. Beginning with Swami and Friends and its image of a provincial train station, Narayan used this location to lay out a whole nexus of south Indian society, its children and its elderly, its poor and its merchants, its sinners and its saints, and even its animals (one book is narrated by a tiger!) Though it may not exist on a real-life map, Malgudi is as fully rendered a fictional location as Hardy’s Wessex or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, but where Narayan differs significantly from these other two is approachability: his work is funny, fleet, and inviting.

The Guide is usually noted as Narayan’s most “celebrated” work. It was the first English-language book to receive the Sahitya Akademi award, and its 1965 film adaption was a massive success in its own right, though Narayan hated it (more on this later). By this point in his career, Malgudi had already been well established in half a dozen novels and two sets of short stories, and Narayan’s career had finally taken off. He was traveling through the United States in 1956 on invitation from the Rockefeller Foundation and wrote The Guide while in Berkeley. Maybe that’s why its main character feels so accessible to American readers: he’s a con-artist with a heart of gold.

Raju is not the first con in Malgudi, but as the protagonist and sometime narrator of The Guide, he makes the strongest impression. The son of a modest shop owner, Raju discovers at an early age that he has the gift of gab and a desire to please, so when casual travelers, often those on work trips, stop at the Malgudi train station and wonder whether anything in the area will tickle their wanderlust, Raju finds himself offering to serve as a tour guide, despite having no knowledge of the regional history or technical specs of any of the nearby “sites.” But he’s brilliant at improvisation, and at sensing what it is exactly these travelers want:

Some people want to be seeing a waterfall, some want a ruin (oh, they grow ecstatic when they see cracked plaster, broken idols, and crumbling bricks), some want a god to worship, some look for a hydroelectric plant, and some want just a nice place, such as the bungalow on top of Mempi with all-glass sides, from where you could see a hundred miles and observe wild game prowling around.

The key to Raju’s success is that he a sharp observer. He notices how often a tourist might say, “I’m only sorry I did not bring my wife and mother to see the place” and incorporates that into his pitch. It’s hard not to hear a trace of other gentle literary tricksters here, like Tom Sawyer on the day he had to whitewash his fence:

Later in life I found that everyone who saw an interesting spot always regretted that he hadn’t come with his wife or daughter, and spoke as if he had cheated someone out of a nice thing in life. Later, when I had become a full-blown tourist guide, I often succeeded in inducing a sort of melancholia in my customer by remarking, “This is something that should be enjoyed by the whole family,” and the man would swear that he would be back with his entire brood in the coming season.

But it is all a scam, even if a scam with no real victims. Raju senses correctly that his customers are there for the romance, not the reality, especially when he’s entertaining “the non-scholarly types,” the “innocent” men, at which point all bets are off:

I pointed out to him something as the greatest, the highest, the only one in the world. I gave statistics out of my head. I mentioned a relic as belonging to the thirteenth century before Christ or the thirteenth century after Christ, according to the mood of the hour.

He becomes a bullshit artist of the highest order, turning Malgudi into a palimpsest of natural and historical achievements — in a sense, doing what Narayan is doing for the reader, “creating” Malgudi as it occurs to him.

Alas, the halcyon days of Raju’s amateur tourist agency end with the arrival of a woman, Rosie, the wife of a historian who makes frequent trips to Malgudi to research cave drawings. Raju is immediately smitten, and Rosie finds him a much more receptive lover than her cold and priggish husband. A whirlwind romance follows, at which point Rosie finds herself branded with the scarlet A (only women are so branded) and a selfishly pleased Raju gets to act as her personal savior.

(There’s something mildly progressive, though, in the way Narayan handles Rosie’s arc. In watching the town’s response to Rosie, and especially the response of his own mother, Raju becomes more aware of the constricted role of women in his society. Implicitly scolding Rosie for her life choices, Raju’s mother…

filled the time with anecdotes about husbands: good husbands, mad husbands, reasonable husbands, unreasonable ones, savage ones, slightly deranged ones, moody ones, and so on and so forth; but it was always the wife, by her doggedness, perseverance, and patience, that brought him around.

Rosie, however, resists this kind of indoctrination and asserts herself and her own well-being against the moral scolds, something that Narayan refuses to punish her for. The real moral criminal here, the book all but assures us, is Raju.)

No spoilers here, but a quick note that the chronology of The Guide is scrambled, so we know from the very first page that things go south quickly, as the novel opens with Raju being released from a two-year prison sentence. Far from the experience crushing his spirits, he seems to have flourished in a controlled environment where his stock-in-trade, offering his services to make people happy, once again yields popularity and success:

I was considered a model prisoner. Now I realized that people generally thought of me as being unsound and worthless, not because I deserved the label, but because they had been seeing me in the wrong place all along. To appreciate me, they should really have come to the Central Jail and watched me.

Still, it’d be a mistake to think that prison reforms Raju in any sense of the word. Not a day removed from the prison, with only the clothes on his back and squatting in an abandoned temple to pass the night, Raju is mistaken for the temple’s wise man and, with his usual penchant for pleasing people, casually decides to play the role and give the man advice, hoping he can make a clean getaway in the morning. As disciples continue gathering, however, he finds himself improvising more and more, especially since the thankful townspeople bring him food. I mean, he’s not hurting anyone, right?

Disaster strikes when Raju’s attempts to placate the town with cheeky aphorisms and stories can no longer sustain them. When an extended drought threatens their well-being, he realizes that…

no comforting word or discipline of thinking could help. Something was happening on a different plane over which one had no control or choice, and where a philosophical attitude made no difference.

It’s no spoiler to say that you’ve probably read this kind of story before, where a con-artist adopting a role finds himself no longer playing but being the person he only intended to imitate. The conventional reading of The Guide suggests that Raju’s life reenacts, in an allegorical manner, the Hindu stages of life, and these do map roughly onto the different phases of Raju’s identity, casting its shadow on the book’s pointedly ambivalent ending. This surface simplicity can be deceptive, though: entire books have been written dissecting the nuances of Narayan’s treatment of these issues, as well as more recent essays on issues like de-colonialization in the novel. There are also open questions in the end: is this a fundamentally religious book set in an agnostic world, like that of Narayan’s mentor and champion Graham Greene?

And even if we read it as conventional allegory, Narayan never treats this material as simply as allegory demands. For one thing, he never loses his tongue-in-cheek narrative style, no matter how serious the events become. For example, when the desperate townspeople are enthralled by the dramatic, romantic image of their holy man standing in knee-deep water to appeal for rain, they decide it has to be that way every day, which Narayan describes with a puckish deadpan:

It had been difficult enough to find knee-deep water, but the villagers had made an artificial basin in sand and, when it didn’t fill, fetched water from distant wells and filled it, so that the man had always knee-deep water to stand in.

Here, in the most serious of scenes, he finds a moment of pure physical comedy. Narayan’s Hinduism is a serious matter taken seriously, but Malgudi is a gentle place, and religious demands never get in the way of a good chuckle.

Notes:

* I don’t want to overstate how progressive a character Rosie is: she has nothing, for example, on Ismat Chughtai’s radical Shamman in The Crooked Line, published fifteen years earlier, or even on his own later heroines, like the liberated Daisy of The Painter of Signs. Still, for a book whose worldview is a relatively conservative one, Rosie’s refusal to be the kind of woman she is expected to be is refreshing, as is Narayan’s willingness to see her happy and successful despite the social forces conspiring around her.

* In his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Guide, Michael Gorra recounts why so many in the Indian literary establishment were initially lukewarm on Narayan’s works, particularly his evocation of a “timeless India,” that is, an India that did not pass through the multi-tiered hells of colonialism and partition, among its other 20th-century challenges, and that this timelessness sometimes makes Narayan seem “tepid and small” when compared to the Rushdies or the Naipauls. On the other hand, the timeless seems to be aging much better than the timely: Narayan knew that evoking “an India that never was” would elicit a kind of nostalgic warmth in his readers, who have remained loyal.

* There’s really no bad place to start with Narayan, but of the Malgudi works I’ve read so far, I’d give pride of place to one he wrote next, The Man-Eater of Malgudi, which pits the mild-mannered owner of a printing company against a monstrous hunter and taxidermist using his shop as a base of operations. Where The Guide scrambles chronology to mask the straightforwardness of its allegory, Man-Eater is deadly precise in its structure, each new development turning the screw a bit more. Somehow it manages to blend slapstick and danger without undercutting either, a minor miracle of a work.

* Because I love nothing more than wildly unexpected meetings of artists: the 1965 film adaptation was initially proposed by Tad Danielewski, father of Anne (i.e. Poe) and Mark (House of Leaves), with an English screenplay by Pearl S. Buck (The Good Earth). The eventual version, in Hindi, was directed by Vijay Anand, and Narayan loathed it, not least because it transferred the specificity of his south Indian outlook to a more generic, more flatly melodramatic north. It also bowed to censorship by turning Rosie into more of a hysterical, dependent mess. Still, it’s one of the most enduring classics of Indian cinema, a massive hit and cultural touchstone in its own right, and Dev Anand‘s rakish Raju is still considered the definitive role of his long and varied career.