I’ve become preoccupied with Myers-Briggs types again. After amusing myself by putting myself, and then my most immediate social circles through the different types (with and without their actual help), I moved onto characters I like, and stumbled upon a few discoveries. Firstly, dramatic stories reveal the truth of Myers-Briggs types: that they’re not categories that human beings can be shoved into, but labels for otherwise disparate values (the most basic part, the introversion/extraversion divide, articulates what value social interaction has to you, and it’s usually pretty clear how inborn that value is). It’s extremely easy to give an MB label to a dramatic character, because they’re forced to reveal and live by those values – Walter White is a pretty clear INTJ, Vic Mackey an ESFJ.

With literature, it isn’t always harder, as we’ll come to see, but there is an extra wrinkle there. Where dramatic stories – especially pure dramatic stories like The Shield or Spartacus – focus on the value-neutral idea of cause-and-effect, literature focuses on harmony-and-contrast; we preoccupy ourselves with an idea until we get bored of it, and then we move onto the next, which raises several questions – why are we preoccupied with this idea, and not another? Why do we linger on this idea for so long, and this for so little? Why are we shown these ideas in this particular order? A literary story inherently has values, and so a literary story can have an MB type applied to it depending on what it chooses to show or leave out.

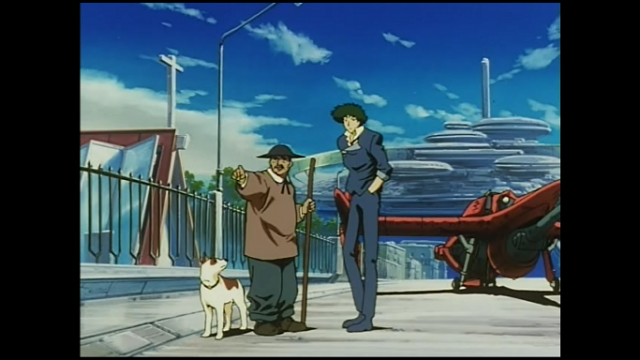

I stumbled upon this idea when I looked up the MB type of Spike Spiegel, protagonist of Cowboy Bebop. It was suggested he’s an ISTP, and looking through the outline of one, it all made sense. Simultaneously intensely private and easily making friends and acquaintances – check. Seeks out novel sensations – check. Doesn’t think too far in the future – hold up, this sounds just like the show! All of this can describe its emotional affect. Every character is vivid, but in a superficial way – everyone we ever meet has an intense sense of style, from clothes to voice, but its very rare that we learn much about who they are, where they’re from, and sometimes even their worldview, and of course anything we learn about our heroes is limited and fleeting.

Individual episodes are structured around vivid setpieces of varying intensity and emotion – the action sequences are obviously joyful acts of ownage, but there’s a sense of fun and play even in depicting a lazy walk around town, as we soak in strange and wonderful details. We linger on a shot of two dudes sleeping, not because they advance the plot, not because they say something about a particular character or a particular theme, but because they look neat (and what makes Cowboy Bebop great art is that its clear the creators find a great variety of things and people neat). On a broader scale, episodes are almost completely self-contained – once a sensation is felt, it’s time to move onto the next sensation, and in fact as the show goes on the sensations get stranger and stranger to compensate for the repetition.

Video games force players to take on a persona via what actions they give them – what you can do, what you can’t do, and what you must do. Mass Effect gives the player a very precise level of flexibility, and so the player character, Commander Shepard, is either an ENFJ or ENTJ depending on morality. However you play them, Shepard is pretty clearly an extravert, as you’re encouraged to talk to not just your crew, but every person in the galaxy. Your reward is not just the broad fun of a vivid and strange universe, but sidequests, which bring with them the fun gameplay and experience points that you use for more badassery. And the fun of the game is combining the fascination of exploring a strange galaxy with an innate sense of justice – the galaxy is a dark, flawed place, and you’ll force your values onto it as you fix it.

Spike and Shepard are fairly simple characters; a character like Don Draper is harder to put into a category because there are so many facets to his personality (and it doesn’t help that he often chases the exact opposite of what he really wants). If I had to hazard a guess, I’d lean towards INTJ. The whole series of Mad Men, though, is another story; with the warm humanism, the long, contemplative spaces between not just scenes or beats but individual sentences, the constant eye on the horizon, the preoccupation with the true meaning behind the characters’ actions, and the eye for patterns in character right down to the props in the background, the series as a whole feels like an INFJ.

What I conclude from this is that works of literature can be seen as personality simulators; whereas an ISTP could watch Cowboy Bebop and say “This is me, and this is exactly how I see the world”, someone else can watch the series and immerse themselves in the pleasures of a different viewpoint – no one who has ever met me would describe as either extraverted or the type to force anyone to do anything, but it’s tremendous fun to lose myself in that person in Mass Effect. And perhaps my violently negative reaction to Steven Universe was less a measure of its quality and more a severe personality clash.