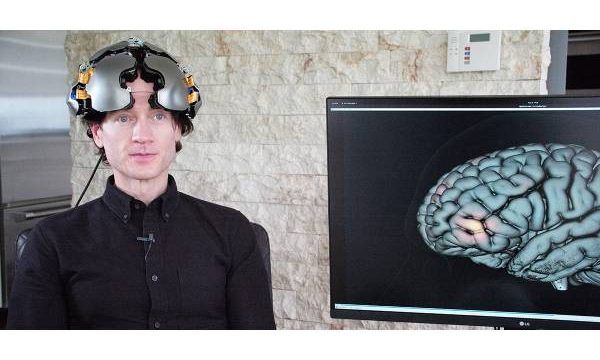

Werner Herzog’s latest doc Theater of Thought presents a collection of interviews with leaders in neuroscience thought and engineering, peppered with demonstrations of devices that allow the brain to control technology (and vice-versa) and considers the possibility of reading thoughts and the difficulty in defining human thought in the first place. It’s an unassumingly lensed (read: shitty-looking) film, which may distract from its more brilliant moments. But considering how many technically proficient docs get scrubbed until they’re personality-free in comparison, Herzog’s curiosity and insight getting filtered through an indifferent deployment of camera technology could arguably be another purposeful statement of theme. As in many works by geniuses, Herzog’s guidance can seem invisible, despite his constant (and dryly humorous) narration.

Herzog is decades away from the man who willed a boat over a mountain or led armies of extras into the jungle, but he’s ever the curious and insightful interviewer. His specificity in questioning leads his subjects down more interesting paths; he doesn’t merely ask one what the role of food is in an imagined brain-oriented world, but asks the scientist is there not value “to fish a trout?” This leads the scientist to ruminate on fishing trips with his own father. In a single query and without a cut Herzog shows a brain projecting the future, then twist back on itself and project a mythical past instead.

(Herzog’s talent for poetic specifics and willingness to wander off-topic are what make him an entertaining interview subject himself, as in his memorable response in an interview with Emily Yoshida where he learns about the existence of Pokémon Go and how a players can compete when in proximity of one another: “Is there violence?” he asks, “Do they bite each other’s hands?”)

The memory’s accuracy is just as uncertain as the guesses about the future, we learn from another interview subject, though its commentary on the fishing digression isn’t underlined. Legends and hypotheticals are uncertain, but motifs can be trusted. Aquatic creatures recur in the film as subjects and visuals. We’re soon introduced to a fascinating creature about 2mm in size, infused throughout with neurons, which can reform itself whole even after getting scrambled in a centrifuge. Later Herzog interviews one of the creators of Siri, opening his line of inquiry with “how dumb is Siri?” While the engineer fumbles with a smartphone to (unsuccessfully) demonstrate its abilities, Herzog’s attention drifts away to images of schools of fish on a monitor behind the subject.

Herzog’s apparent disinterest in one of the most commercial applications of so-called “artificial intelligence” is funny on its own, but he wastes almost no effort on this damnation before pivoting to what he does find fascinating about his subject’s interests: the fish. The vivid underwater images that Herzog zeroes in on were captured by the AI researcher (and they’re hands down the best images in this drab film) and the director engages him in speculation on how schools of fish communicate rapid changes in direction seemingly through a kind of groupthink.

Herzog is the author of the film’s rapid shifts in direction, of course, and we follow in the wake. Theatre of Thought fulfills a basic mission in showing cutting edge neuroscience technology and its inventors. But Herzog dabbles in some old-fashioned telepathic messaging as he closes the film with more fish mysteriously moving in tandem and shots of soldiers goosestepping in unison at their posts. Like all tech, these machines that augment, assist, and redefine reality – including cameras – will never be as important as the intentions of the people who wield it.