We take it for granted that anyone reading this has read Watchmen and seen the film. So, SPOILERS ahead.

DN: My copy of Watchmen has a quote from Damon Lindelof on the back (“The greatest piece of popular fiction ever produced.”), and you can really see the influence of the comic on Lost in the structure of the story. There’s a central dramatic push driving the story – the Comedian is murdered, and everything that happens in the present day is pushed forward by that in some way – but we also get regular flashbacks to the backstories of each character, usually set off by the action. In this case, the Comedian’s funeral causes each major player to reflect on some moment they shared with him, which we get in chronological order, climaxing with Moloch telling Rorschach about an incident a week before his death.

Obviously, Edward “The Comedian” Blake is a vile, vile man, attempting rape, murdering a pregnant woman, and generally having a ball during a riot as he nihilistically enacts violence on civilians. His story is of a nihilist who finds something so awful that it actually breaks him, which isn’t a story done often and definitely isn’t something I’ve seen done as well as here – I’m particularly struck by his line “I mean, I done some bad things. I did bad things to women. I shot kids! In ‘Nam I shot kids… But I never did anything like, like…” because the interesting thing about being a cynic or a nihilist is the world always has a way of testing your commitment to it – think of all those great works of cynicism, like The Simpsons or 30 Rock, that looked downright naive after the election of Trump. Everyone who thinks of themselves as a cynic has had or will have an experience like his; no work captures that experience in its totality like Watchmen.

What I find interesting, though, is that the Comedian is genuinely a perceptive guy. He has the number of everyone he talks about, and even accurately notes that America would have “gone a little crazy, you know, as a country” if they’d lost Vietnam; he even figures out Hooded Justice has a fetish for violence at the tender age of sixteen. Part of his worldview must come from the fact that he can generally take in information on people non-judgmentally; you can see how someone naturally inclined to soak up information on people and naturally inclined to not care either way about it and naturally inclined towards violence would make the choices he does.

Your initial thoughts on the chapter?

ZZ: Here, as in chapter one, Watchmen’s sense of time resonates; the deepened flashbacks and older characters we get in this section keep up that sense of nostalgia and complicate it still further. The flashbacks completely avoid falling into pointlessness, and through a lot of different tactics. Sally Jupiter’s flashback shows us that she draws a different, and sharper, distinction than her daughter on what is degrading and what is not–that their moralities are not the same. (I particularly like the inclusion of the final beat with Hooded Justice during his rescue of her, where he effectively confirms the Comedian’s assessment of him by completely disregarding the woman he’s saved: “And for God’s sake cover yourself.”) Adrian’s shows us that he has been thinking for years about the question of how, if at all, the world is to be saved from itself.

But there are two particular details that land for me even more than the others. The first, and smallest, is our one-line glimpse of Rorschach’s relative sanity and balance–in the flashback to the Crimebusters meeting, he’s someone who speaks fluidly and thinks about the logistics of running a superhero organization. It’s jarring because Rorschach is so completely himself–it’s natural to suspect that if something made him that way, it was something much more distant, and while that’s partly true, the world of Watchmen is such that things never stop happening. Things and people never stop changing.

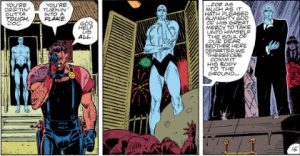

The other real standout for me is the Comedian’s meeting with Moloch, which obviously landed for you too. It’s interesting to me also from the standpoint that it’s where the “life changes constantly, and changes us constantly” thread intertwines perfectly with its opposite, the nostalgic longing for an unchanging time. These two were enemies, but your enemies become, as Rorschach says, the people who leave you roses when you’re gone, because you were significant to them and because the two of you were the last citizens of some other world. It’s a change, but it’s a change that scratches them both down to their bedrock, and finds what they have in common.

In a way, it’s a vindication of Adrian’s work: one horrified man making peace with another. I thought we were bad, but I had no idea.

This is a chapter that does an amazing job, as you said, with cynicism and nihilism and with their limitations. The Comedian is one of the first to realize that the problems of the world go beyond other guys in masks, one of the first to make no distinction between superhero bang-pow violence and the real-life violence of shooting a pregnant woman. But if Watchmen has a world where realistic people have tried and failed to become iconic characters of four-color morality, it also has a world where these people, with their imitations, are approximating some Platonic ideal, something that is real, where hardened reality does not necessarily have the final say. The Comedian, for all his nihilism, is unprepared. He can mock “let’s use superhero authority in a superhero world!” as inefficient, but his disillusioned state is “use real, authoritative violence in a real world.” He doesn’t go all the way to “use authoritative superhero violence in the real world,” and he didn’t even realize you could.

What are your thoughts on the flashbacks?

DN: Another tiny detail I notice for the first time: Rorschach’s trenchcoat is open in the past when it never is in the present. The traumatic event literally closed him off.

The thing I like about the flashbacks is that they actually literally are flashbacks rather than just achronological storytelling. The characters’ are actively choosing to remember what we see right at that moment, and it says something about what they choose to remember. Sally and Dan see the gleeful violence from two different angles. Jon and Adrian see the perceptiveness, again from completely different angles; Moloch is lucky enough to see the vulnerability, which will set up the Comedian’s final punchline with Laurie.

Actually, this makes me think of one of those other narrative tools I love that Watchmen joyfully delivers on: the ability to contrast and compare the same idea expressed in two different characters. We’ve already done that with Rorschach and Adrian, two men who forged themselves into an ideal; here, we have Jon and Adrian as two people who see the world from a global perspective, and that makes them alien and distant. You said that Jon sees the world in icons and concepts; the same is true for Adrian, but he embraced different icons and different concepts, ones simultaneously more rooted in humanity and yet more abstract. You could then leap to Rorschach and Jon, who are, again, alien and distant, but on completely opposite scales, one cosmic, one individual.

(This also sets off a storytelling idea: to generate new characters, copy one character and keep one trait the same while reversing another)

And now I circle back to the Comedian. Like Adrian, he sees things on a broader, society-wide scale. Like Jon, he’s apathetic about what he sees (though not quite as much as he claims). Like Rorschach, he chooses to act on an individual scale, perhaps on an even more individual scale than Rorschach. Adrian and Rorschach respect half of his perspective, as if he finds the mid-point between their two viewpoints. It’s oddly sweet that Rorschach is the one to give the Comedian a real eulogy; the comic nearly ends with Adrian giving him a similar one.

ZZ: We get that repetition-from-another-perspective technique here when we again see the Comedian’s murder, panel-by-panel: this time, his death is intercut with what we now know about his life. It’s the same event, but played in a different key, and it produces a different question. Not, this time, who murdered the Comedian, but what pushed him into the acceptance of his death when it comes? Rorschach is now primed to recognize that as a line of inquiry.

I like your different angles on Jon, and I’d add Jon and the Comedian as a pair here, too, especially with what you said about the flashbacks being the characters themselves remembering these events, not the narrative just ducking back. The Comedian said it: they’re both guilty of slipping away from the values of humanity. (It is, as Laurie notes, only official orders that have him wearing a suit to the Comedian’s funeral.) The difference isn’t just that the Comedian does it violently and aggressively and Jon does it only by “driftin’ outta touch,” it’s also that the Comedian feels shame about it and Jon doesn’t. You can’t betray something you have no real relationship to.

That’s a spoiler bonus that I hadn’t noticed before: Eddie Blake reacting to his murder of the mother of his unborn child by, within seconds, focusing on how Jon is treating Laurie, “Sally Jupiter’s little gal,” an instinctive reach to blame that’s also, in retrospect, an instinctive reach to protect the person he hasn’t failed yet. There’s a dark joke to that he would appreciate.

My favorite joke of the chapter, and maybe of the book, though, is Rorschach and the non-FDA-approved cancer treatment drugs. Intensity enough to track down the one illegal thing in the place–and something non-obviously illegal, too–compassionate enough in the end to leave the drugs there, and adherent enough to his own values to plan to report the drug company later. All in six panels.

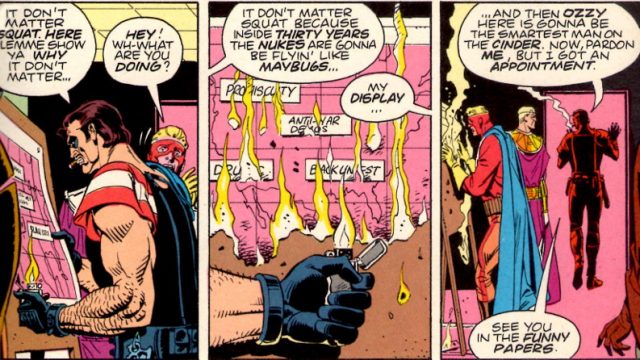

Which reminds me that we see more of the costumed hero work in this chapter, and the scope of it is incredibly vast: costumed villains, riots, Vietnam, and the paternalistic concerns of the Crimebusters (“promiscuity,” “anti-war demos,” and “black unrest,” among others). It’s the question, again, of what kinds of problems it’s possible to combat through these methods–or through any methods, in some cases–and what kinds it’s not.

And in another one of your double-and-reverse characterization bits, Adrian and Rorschach come up with very different answers to that, both here and elsewhere.

DN: I really like your phrase “played in a different key”, because it perfectly captures how literary structure works – information where the emotional power comes from the information it’s surrounded by. It reminds me of Alan W Pollack’s analysis of “Free As A Bird”, where the A Major chord, so normal and almost triumphant in the verses, becomes dizzying, alien, and terrifying in the bridge. We even get exactly one extra panel to change things up, a closeup of the Comedian’s terrified expression just before he hits the pavement; we know him a little better, and so his terror means more than it would have at the start of the story (it also ties him, visually and emotionally, with “The Black Freighter” when we get to it). Perhaps it’s part of why Watchmen and other works of literature feel like they have a greater scope, even sensory experiences like Cowboy Bebop.

Your great observation on Jon versus the Comedian makes me wonder what the comic implies about ‘humanity’, meaning the adjective not the noun. Jon is inhuman. Jon does not care about people. Adrian is human, the Comedian is human. Both care about people, though Adrian misses out on the specifics for the grand picture while the Comedian actively attacks specifics. Perhaps your last sentence is it – that humanity means having a relationship to other humans. Adrian has no meaningful relationships with individuals, but a strong relationship with humanity-the-noun; this enables his horrific acts. Dan and Laurie have several meaningful relationships, and while they can’t achieve the spectacular acts Adrian and Jon do, they can survive the comic in a way that Rorschach can’t.

My personal favourite joke of the chapter is “You know that kind of cancer you eventually get better from? […] Well, that ain’t the kind I got.” Speaking of faces you don’t see anymore, it’s the kind of joke you don’t hear much anymore; the diction and structure and level of dryness are very old-fashioned, suited to a guy like Moloch. It sounds like something out of an old pulp novel. I actually like Rorschach’s reaction (never thought about how specifically aware of illegality Rorschach would have to be til you pointed it out) more as a bit of sympathy; he’s just a fraction more compromising than you’d expect, or than he makes himself out to be.

ZZ: What you’re saying about “humanity” brings me to our next installment of Under the Hood, too, which–appropriately enough for an excerpt following a funeral and a quiet eulogy–is primarily an elegy to the costumed heroes stolen away by time. Mostly, as Hollis points out, too young. They were briefly celebrities and they died celebrity deaths and lived with celebrity cover-ups.

And that’s where relationships come back in. Hollis mourns his lost friends as individuals, but, looking at the Minutemen dispassionately, he wishes they had never been. There’s a sense of well-intentioned shallowness here, part of which Hollis is critiquing–”choosing to dress up in gaudy opera costumes and express the notion of good and evil in simple, childish terms, while over in Europe they were turning human beings into soap and lampshades”–and part of which belongs to him–”the villains we’d fought with were either in prison or had moved on to less glamorous activities.” Watchmen keeps coming back to that lack of glamour as something that is both fundamentally human and fundamentally going to frustrate and depress humanity. If the Minutemen as a group had an original sin, maybe it’s that they treated evil as something that could be eliminated by the right battle or the defeat of the right villain; they made fundamental moral struggle into one-on-one combat. On an individual level, they might have known better–Rorschach, as you said, shows a sympathy for Moloch that he couldn’t if he couldn’t grapple with the man as a person in his own right–but as a group, they sold an image and a philosophy.

Part of Watchmen, I think, is that you have to take responsibility for your ideas as well as for your actions. It’s a ruthless morality, but Moore is sympathetic enough to his characters that I think it’s exacting rather than unforgiving.

DN: And that same sin eventually passes to Adrian.

What strikes me is how haunted Hollis is by the consequences of his actions. As clear as he is about his belief that their initial actions were good, he honestly believes he’s made the world a worse place – I read him saying “The damage had already been done” and it strikes me in the same place as a certain Southern gentleman wishing he’d never met a particular cop. The tragedy happened a long time ago, and we’re still sifting through the consequences. Under The Hood is a true confessional of a man trying to explain why he was responsible for something terrible (which makes me wonder about his expressed belief that Dan was a better Nite Owl and that it was a shame the Keene Act passed).

The flip side to this is that you genuinely do feel the glory days, even through the melancholy. Being a superhero honestly does sound cool, with Hollis detailing the practicalities of the profession, and laying out the successes of the individuals – the two chapters we get neatly show the rise and fall of the first generation of superheroes. Through Hollis’ viewpoint, we see how the characters must have learned and grew, and developed into a community. I look at what breaks up the group, and I see not one big tragedy but lots of miniature, personal ones. This world is built on a foundation of dead bodies.

Do you think that Hollis is, in Under The Hood, taking responsibility for his ideas?

ZZ: I think at the very least, he’s trying to, and in all the ways you mentioned. He knows that something has been put into motion that he can’t take back (and that no one else can take back, either).

I really like what you said about how personal the history of the first generation of superheroes feels. There’s a genuine love underneath any criticism Hollis offers: history is a time when you knew everyone else, and Hollis’s memoir has that feel to it even when he’s trying to make a different point. This is that humanity thing again: Hollis has principles, but his connections are to people, and so how he relates to people does not necessarily have a huge Venn diagrammatical overlap with his ideology.

As our story opens up, we’re seeing ideology work itself out on people, which changes everything.

SCATTERED THOUGHTS:

- ZZ: I alluded to this up above, but that scene between Sally and Laurie is painful: Laurie’s ideas of what Sally should feel are getting in the way of her seeing what Sally does feel, and Sally can’t seem to tell her. That’s partly the generation gap, but Moore and Gibbons also create the feel of a woman who has raised a daughter who is smarter and who therefore believes she is better; she’s created her own dismissal and she knows it.

- DN: I forgot to bring up how real the Laurie/Sally scenes are. Yes, fine, I’ll put out the cigarette after all your hint-dropping, Mother.

- ZZ: The flashback scenes have more vitality to them right now than the scenes in the present, which is half the point. The age of superheroes was never perfect, but its emotions were stronger and its intentions were grander. That’s half the appeal of superhero/comic book/mythic storytelling in the first place–it lets you easily tell huge stories about powerful feelings.

- DN: Ownage-wise, this has Rorschach’s infamous surprise attack out of the fridge. Of course, the Comedian’s life was a constant wave of ownage.

- ZZ: Jon is in a gradual striptease throughout this chapter, losing clothes over time: he starts off with a full top-and-bottom leotard (with visible midriff) in the Crimebusters scene and is down to just the fig-leaf bottom in Vietnam and will, of course, be down to nothing, wearing clothes only when ordered to, by the time the present timeline begins.

- DN: One big hint as to the Sign Man’s identity as Rorschach, when he sees Moloch walking out of the cemetery.

- ZZ: Both Adrian and the Comedian sit out most of the Crimebusters meeting, but Adrian has a throne and the Comedian has a chair with his feet kicked up on the table. I feel this is an accurate summary of their characters.