We take it for granted that anyone reading this has read Watchmen and seen the film. So, SPOILERS ahead.

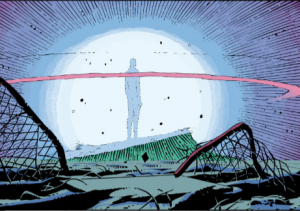

ZZ: Coming off the tragedy of the Comedian–the Pagliacci of it all–we have the tragedy of Dr. Manhattan, who paradoxically has nostalgia and history but no past. He will, as Janey Slater points out, never get any older. He will never be required to make exclusive choices, not when he can divide himself to pursue different outcomes. He can leave behind people and places, but, past the glassed-in and unreachable Osterman, he has no way to leave behind other versions of himself.

He’s the Don Draper of Watchmen, the one who most seems like he will stay the same and be the perfect man of one moment passing into being the imperfect man of the next, the one who learns, chameleon-like, how to do what is best only to have that be insufficient. He’s a scientist, of course, so he uses evidence instead of social mores–the photograph he takes with him to Mars is proof that he used to be someone else and love someone else; he doesn’t say that doesn’t know anymore how to make Laurie happy, he says he doesn’t know what stimulates her, he keeps it in the realm of the quantifiable.

This is why the frame Veidt hangs on him is so brilliant. With someone as powerful as Dr. Manhattan, there’s no external force that you can really bring against him; Veidt needs to get him to convict and exile himself. (Rorschach gets this intuitively and immediately, of course, because it’s a gorgeous bit of conspiracy theory logic: of course the freely-made choice is the product of behind-the-scenes puppetry.) And to get a man this logical to do that, you need evidence, and a persuasive amount of it. It’s Veidt’s good luck that this comes right on the heels of Jon’s breakup with Laurie, so it all cascades together: here is one more human thing you have unwittingly destroyed, and you don’t even get to understand how. The evidence says that it happened, but it doesn’t say why.

DN: Ooh, that’s good. The thing I notice from all of Doc’s choices, in general but especially in this chapter, is how he’s always delivering what he thinks people want, but skipping over social mores entirely to get straight to the point. He has to go to the TV station, so he pops in without warning. He has to be a darker shade of blue, so he turns blue. Laurie wants to be sexually satisfied, so he doubles himself to pleasure her as much as possible, and triples himself so he can do some science at the same time. The tragedy of Jon’s life is that he’s spent it giving people as precisely what they ask for as he can muster. More exactly, he’s trying to put his life in perfect, clockwork (!) harmony, but if I’ve learned anything from Bruce Almighty, it’s that not even God can mess with free will; it makes absolute sense to me that Jon would believe the only thing he can do is leave Earth and humanity entirely. If nothing he does works, he’s better off doing nothing.

Meanwhile, the story truly begins to fragment. Now that the players and the premise are established, we spend almost the entire chapter jumping between two things – between Jon’s interview and Dan and Laurie fighting street punks, between President Nixon and Jon on Mars, and between reality and the comic-within-a-comic Tales Of The Black Freighter. I lovelovelove that Moore and Gibbons took the time to imagine that superhero comics would take a nosedive in the face of actual superheroes, and that pirate comics would rise in response, and the comic goes on to dovetail beautifully with the story – we’ve secretly been given characterisation for Adrian all this time, when we naturally interpret it as another detail in the same vein as the Nostalgia ads and the threats of war on the horizon; a vague feeling of oncoming doom.

What attracts me to The Black Freighter especially is how clear-eyed it is in vision; not only is it distinct from the narrative around it (Dave Gibbons goes wonderfully ghoulish in a way that he doesn’t in reality, even during moments of violence, up until the final chapter), it’s distinct in a way that suggests an actual artist with his own themes and preoccupations, and those themes are a response to the world he’s in. It’s very rare to see stories-within-stories done with this level of sophistication – the only other thing I can think of is Night Film by Marisha Pessl.

ZZ: I’ve always loved how The Black Freighter works as worldbuilding. This is a culture that’s become skeptical of both order and the attempts to work justice outside of order, and pirates are such an excellent way to work outside of both of those social fixations: lawless and self-interested. They’re fundamentally unsafe, but they aren’t pretending to be anything else; pirates promise no panacea. In that way, they’re down there with the rest of the world, able to act outside of it and on its behalf–because they’re violent, because they’re capable, because they’re better-informed–but there’s no messing around with the idea that they have the moral right to do so.

I also love how baroque the story and its language are. Like you said, it’s entirely convincing as a piece of art in its own right rather than as just a little metatextual experiment of Moore’s: I’d read it on its own, for sure. Elaborate prose has never been a barrier to entry on the right kind of pulp fiction–if it were, Lovecraft would have vanished long ago–but it’s something that rarely shows up in homages. Unsurprisingly, though, Moore gets the appeal of language that is perfectly keyed to the concepts its dealing with; gets the way antique phrases and ancient sensibilities can feel truer when it comes to talking about the immensities of life, death, and monsters. That he does that in The Black Freighter, and gains the weight of it, while still constructing a story that tackles all the same subjects in a modern vernacular, well… there’s a reason the guy is one of the greats.

And, as you said, the art is incredible. One thing I particularly noticed this time through is how often the color palettes of the Black Freighter panels repeat themselves in Dr. Manhattan’s panels: the lighter blue of that ocean to the ordinary blue of Doc’s skin, the darker blue to his adjustment of it for the cameras, all the inky purples in that story showing up constantly (what spills out of whatever Laurie pitches at him, the decor of their apartment), and so on. It’s a really nice, subtle touch. And, I think, a key thematic one. If the disillusionment comes partly from the characters thinking they no longer live–and maybe never lived–in a world where they could be part of struggles that have this Nordic saga blood-and-honor feeling to them, the bleeding-over of The Black Freighter into Watchmen proper is a reminder that that’s not true. It’s not the perfection of old superhero comics–it’s the grubbiness and moral dubiousness of pirates–but it’s there all the same.

DN: That brings us to the major element this chapter introduces rather than develops – the boy and the newsvendor. There’s a touch of, if not parody then wryness about them; the newsvendor opens up the chapter explaining that his vast perspective on the situation gives him the proper point from which to judge what should happen, only to reveal himself as contradictory and blunt, and I see Moore teasing both me and himself there. The newsvendor is a very Discworld character. Next to that you have the boy, who doesn’t get many lines but does get in a joke about not realising what a serial is despite being in a serial comic. Their final appearance in this chapter is very sweet, when the newsvendor has a very Comedian-esque response to the news on Russia and tries to do something good while he can. The boy will be wearing that cap for the rest of the story. We also get an actual appearance of the Sign Guy (if only we knew his name), and one of my favourite gags in the book:

“I see the world didn’t end yesterday.”

“Are you sure?”

I also notice this time that his monologues are countering the sailor’s monologues in The Black Freighter, though not in any specific way; I think it’s just the attitude of the comic to keep ping-ponging between two ideas, and they don’t always have to relate – the same way that Lost never drops us straight into the action and that doesn’t mean anything beyond just feeling right. Inna final analysis.

ZZ: I spent some time on this read-through trying to tell what we’re supposed to know about Sign Guy and when we’re supposed to know it, and on that note, the perfect bit of characterization there–in addition to the joke you mentioned–is the combined pessimism/optimism of “the world’s going to end today for certain”/”keep my paper for me tomorrow.” What’s dread in comparison to the determination to keep coming back to soldier on through it?

Someone thoughtfully brought up harmony-and-contrast today, and I think that’s a good way to look at the way the method of the storytelling works here. Watchmen strikes me as a drama told with the mechanics of literature, and this chapter is a sophisticated example of that. Everything weaves together and makes a top-down picture that’s meaningful, in addition to having forward momentum. There are big, accelerating events here–the break-up, Dr. Manhattan leaving Earth–but they’re given the space and the mulling-over that literature provides, and they’re contextualized by other stories as well as other choices.

And the choices make their own relevant contrasts: Doc’s agitation makes him teleport everyone in the television studio outside of it, leaving himself alone; his calmer reflection makes him exile himself, leaving the world to the people he can’t understand or satisfy.

Is it time for our regular check-in with Under the Hood? Hollis has a lot of insights into what Doc and change mean for the world, and part of that is disposability–first of the last of the masked heroes, and then, maybe, of everyone else.

DN: I would personally charactise the story the other way around – as a work of literature where, like Lost and The Wire after it, the individual pieces are made up of tiny dramas, but the effect is the same either way. It’s a big complex ecosystem where decisions bounce off each other to that driving effect; contrast with Mad Men, which is also made up of a million pieces but doesn’t have that sense of an ecosystem.

Under The Hood shows us the dying embers of the original Minutemen, with Hooded Justice emerging as the most interesting, or at least coolest member. He was the first hero the world (at least through Hollis’ eyes) saw, and the one who managed to live out the superhero ideal the most effectively, and I love the Hoffa-esque nature of his disappearance. I think I almost want him to be the old guy in chapter one if only because I love the idea of the original superhero getting away with it and living a happy life.

We then lead into what Hollis calls the “New Breed” of heroes, i.e. our generation, and the beginning of his transformation from Nite Owl to Hollis Mason, Retired Hero. I love it as an honest moment of recognition and as a moment of someone genuinely transforming themselves; the pleasure I get from Hollis’ final paragraphs is the same that I get from every episode of Community. You said that one of the major themes is that life changes, and changes us; seeing someone actively change in a positive direction, especially in such a disillusioned story as Watchmen, is always great.

ZZ: You now have me picturing Under the Hood as narrated by a retired Jeff Winger, and most of it works well: “Real life is messy, inconsistent, and it’s seldom when anything ever really gets resolved. It’s taken me a long time to realize that.” If Hollis is the only character we see finding peace, he finds it both through knowing what he can and can’t repair (there’s a big difference between cars and the world) and through accepting, paradoxically, both his consequence and his insignificance. What he did changed the world, and he knows that, but he also knows that the world is much larger than he is, and that it’s possible and understandable for his prominence in it to fade.

Appropriately, too, he’s the one who draws a sharp line between masked heroes and superheroes, and who sees himself as firmly one of the former: not even so much first among equals as most active among equals.

(He should have perfect, peaceful twilight days, but he won’t: part of the ruthlessness of Watchmen is that events just keep unfolding and that no one’s life can be effectively summarized until after the end of it–if then.)

DN: Really, his transition into his twilight years is motivated by the same attitude that got him into masked heroism in the first place: the self-awareness to figure out what he wanted to do, and the self-awareness to recognise what he could do. Of all the comparisons we could make, I find myself making one I never would have conceived of alone: Hollis and Rorschach. Both have a highly developed sense of morality that looks at themselves as individuals; both live their morality day-to-day, not thinking too much about the future beyond the next day. The difference is, Hollis tailors his actions to fit into society, and Rorschach doesn’t. Unfortunately, Hollis’ morality won’t save him any more than Rorschach’s will.

SCATTERED THOUGHTS

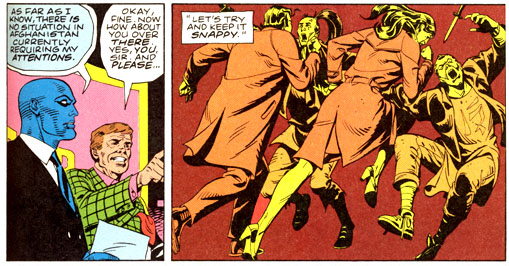

- DN: Ownage: We didn’t even touch on Dan and Laurie’s fight with the street punks. My favourite part of that is Dan’s two-finger punch thing. It’s also where we start seeing that Dan is actually a good-looking guy without his glasses.

- DN: Excellent joke when Rorschach having stolen the sugar packets comes back on Dan.

- ZZ: Strongly seconding both of these. And Dan and Laurie’s ownage nicely contrasts with the ineffectual blustering of the agents who come to clear out Laurie and Jon’s apartment: he’s stuck with secondhand knowledge (“if our psychologists are right”) and secondhand ideas (the misogyny of “your meal-ticket” is nicely played here, especially with the following panel of Laurie’s bra going into a nuclear hazard container).

- ZZ: Small character touch: Rorschach always calls the Comedian the Comedian and Doctor Manhattan Doctor Manhattan, but Dan is Dan, and when Laurie corrects him from calling her “Miss Jupiter,” he actually does start calling her “Juspeczyk” per her request. There’s a basic differentiation there between active and inactive heroes, but also a basic respect for whoever he’s interacting with. (And, with Dan, an affection.)

- ZZ: And one more small, bitter joke: Jon arriving home to find a sign painter still adding the nuclear symbol and caution warnings to his door. Awkward.