We take it for granted that anyone reading this has read Watchmen and seen the film. So, SPOILERS ahead.

ZZ: This is another contemplative Watchmen chapter, but not contemplative in the Dr. Manhattan mode, but in the more violent, confrontational, disorganized Rorschach mode. So in one way, it’s another round of “here’s how a man became a superhero,” but it’s more inherently dramatic than Jon’s story. Rorschach deliberately made the choices, step by step, to become the character we know; his telling of that story isn’t meditative but assaultive, a conscious (and effective) attack on how his doctor sees the world.

It’s a revealing action. He’s cunning enough that, up until this point, he’s been deliberately misleading the doctor, claiming to see butterflies and flowers in ink blot tests where he can really see only violence. But when that plan falls through, he doesn’t try for a more subtle lie, he just starts expounding on what he sees as the truth. He likes his binaries, so he goes from full deception to full revelation. And it’s worth noting how innocent he imagines innocence to be–it feels like a more tragic version of the “Clark Kent is who Superman imagines humanity to be” speech in Kill Bill. He’s smart enough to know to lie but, in a strange, sweet way, not worldly enough to know how to lie in a way that will be thoroughly, lastingly convincing.

The story he tells feels like an ancestor of the “no half-measures” speech from Breaking Bad. Walter Kovacs thought he could play at being Rorschach; that being Rorschach could mean letting criminals live and could include having friends. He’s confronted with a world that was more awful than even he had thought and his response was utter transformation, utter compulsion. There are seeds of the ending here: he practiced accommodation once, and he will never do it again.

What do you make of his backstory? It mostly works for me, though I have some complaints that I’ll get to as we go along.

DN: I’d never thought of Rorschach’s story as an action within itself – of course he’s thoroughly (and slightly implausibly) owning Dr Malcolm, but your description of his lie vs his truth was something that had never occurred to me. Thinking of it from that perspective, there are surprising nuances we can get out of the idea that Rorschach’s view is, if not unique, specific. The basic conflict between Dr Malcolm and Rorschach is that there’s a singular explanation for his life – as he puts it, that Rorschach displaced his anger at his mother onto criminals. But that theory depends on Rorschach lacking self-awareness, which is completely untrue. Rorschach sees his life as a series of decisions, decisions made with full clarity of vision – he refers to his younger self as ‘soft’ and ‘naive’, implying that while his decisions were wrong, they were the best he could do with the information he had. In that respect, the doctor’s initial diagnosis isn’t wrong, it just doesn’t capture the full picture – part of which is Walter’s relentlessly moral and relentlessly logical outlook.

“The Abyss Gazes Also…” is much subtler about it, but it does capture Rorschach’s view of the world as completely as “Watchmaker” captures Jon’s, and part of that is as you said because of the more dramatic structure of his life story, because Rorschach sees his life through the development of his morality; he witnessed things, he allowed himself to process them, and he acted upon them. His final act as Walter Kovacs is simply the logical conclusion of the same decision he’d been making his whole life.

It’s an overall effect powerful enough for me to forgive a few elements; I’m certain there are people who grew up with abusive prostitute mothers, but that general kind of thing has been used and abused for so long (especially for extraordinary people like Rorshach or Don Draper) that it pretty much just glides by me now – I’m starting to think that people with abusive parents write about it because it’s what they know, while people without abusive parents write about it because they think it’s inherently more interesting. The rest of Rorschach’s backstory is more effective to me, particularly when he gets to the Blaire Roche case and Moore and Gibbons let the images silently tell the story before allowing him to conclude it. There are also hints of the world outside Rorschach’s view of it; I love that his mask can only exist because of Jon. He isn’t a mindless automaton blindly following instinct, but he’s not a self-made man either.

ZZ: I’m glad you noted the implausibility of Dr. Malcolm getting quite that thoroughly owned. It’s a great moment that falls just a little flat because I don’t entirely buy that he would have the job he does and yet be blindsided by the darkness of life or that he would be so dunderheaded as to believe Rorschach’s “innocent as a little lamb, all I see are flowers” routine… though to be fair, at least the former and the latter are internally consistent. The man who would uncritically believe Rorschach continues uncritically believing Rorschach.

An interesting thing to read alongside this particular chapter, I think, is Theodore Sturgeon’s Some of Your Blood, a realistic vampire novel told primarily as a series of letters and psychiatric reports concerning a man who has been discharged from the military and (possibly erroneously) confined for an extensive period of time to a mental hospital. It’s deeply interested in unreliable narration of both the “person telling the story doesn’t realize the nature of the story they’re telling” kind and the “person telling the story is being deliberately misleading” kind. It was published in the sixties, and, given Sturgeon’s reputation in the horror/speculative fiction field, I’m reasonably confident Moore read it. I’m really curious if it was an influence here in how Rorschach first misleads and then horrifies Malcolm.

You picked out exactly the part of Rorschach’s backstory I wanted to (mildly) complain about: the abusive prostitute mother. Like you said, it’s used enough that it’s become almost invisible, and I’d have no complaints about it if I didn’t think Moore could do better than this particular execution of it. There’s a hamfistedness to Walter Kovacs’s mother yelling, “I shoulda had the abortion!” that there’s not to the handling of the Roche case. I can make a case for that being deliberate–Dr. Malcolm assumes Rorschach’s mother is the root cause of everything about him, but Rorschach doesn’t spend much time on her and Moore doesn’t invest her with much specificity or significance, indicating that the real interest is elsewhere–but it still doesn’t work as well as everything else here does.

But when the rest of it does work so well, I feel mean for quibbling. Certainly that panel of Rorschach–then Kovacs wearing Rorschach’s face–finding the pair of underwear in the furnace is both subtle and devastating. It makes sense that this would complete his transformation. It’s not just the crime, it’s the fact that the cover-up gets so monstrous and so savagely inattentive to the human impulses of burial and care for the dead (something our own Grant Nebel has talked about in relation to The Shield). It’s a violation on every front.

And it contrasts nicely with his own attentiveness to the dead–to the Comedian’s funeral and to Kitty Genovese’s unwanted dress. The Kitty Genovese story was something I wanted to make sure we talked about. What did you think of its inclusion here?

DN: I never actually realised until now that this was the actual Bystander Effect case – I knew of the case, but never connected the names. I’m a little queasy about the tastefulness of connecting a real person’s murder to a story about superheroes, but at the same time I can’t get away from how well it works – of course Rorschach’s personal connection to a brutal crime would make him leap into action. In the time since the comic was released, it’s become public knowledge that the so-called Bystander Effect was exaggerated for the news story – there were not 38 witnesses, none of them had a clear view of what was going on, it’s unlikely anyone could hear Genovese screaming as her lung was punctured, and a few people did in fact call the police – and yet it still works in the story, because it’s not about her, it’s about Rorschach reacting to something he read in the paper.

What I find interesting is how Rorschach’s misogyny and morality are both present in his telling of her story. He cuts up a symbol of a woman, and puts on the mask when someone actually cuts up a woman. My take on Rorschach is that determining his sexuality – gay, straight, bisexual, or asexual – is impossible because of his fucked-up-ness, and what’s important is that he’s repulsed by sex, associates all women with sex, and that these facts are irrelevant when a woman is brutally murdered.

If Rorschach’s story has a connection to any story outside Watchmen, it’s Breaking Bad, in the sense that it’s a basic dramatic story about someone carefully refining themselves to become an icon. Dr Malcolm believes that the explanation for Rorschach lies in his early childhood, but it goes back even further than that, right down to his makeup: Rorschach needs to do good, and he’s willing to keep refining the process of doing so as new information comes in. His mother, Kitty Genovese, Blaire Roche; to him, they’re all points of data that collapse into a single action: being Rorschach.

ZZ: I agree that the story still has its desired impact here. The later revelations about the case may mean that we live in a more bearable world than Rorschach had thought, but there’s still no reason for him to have known that. I think you could even make the argument that this is one of those story details that only gains added resonance from the way the cultural baggage attached to it has changed. It makes the case into its own kind of Rorschach test–there’s a difference between people who would look at the reported legend and see it as grim confirmation and people who would look at it and say, Wait, I think there’s something missing here, or even look at it and discover the Bystander Effect–and Kovacs’s interpretation of it, and his wholehearted belief in that interpretation, means that he’s operating as though he lives in a darker and more heartless place, and what he sees afterwards is taken to confirm that. As the Doctor once put it, the universe is a big place and everything happens somewhere, so part of what defines a person are the events that they highlight as significant. You decide what the world is (character), and then you decide how to respond to it (morality). I think the characters in Watchmen all vary on those questions to different, and revealing, extents.

Another thing I wanted to talk about in relation to Kitty Genovese was the huge impact her murder and the framing of it had on pop culture at that time, and maybe genre culture especially, since genre is drawn to dealing with violence. I know all I’m doing for this chapter is apparently developing a reading list of offbeat classics, but I have to mention Harlan Ellison’s “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs.” It opens with a woman observing such a murder and doing nothing–except meeting the eyes of the man opposite her who is also looking down at the scene–and then falling into a vortex of self-recrimination and nasty, mean-spirited eroticism. In “Whimper,” the world is as Rorschach sees it, corrupt, depraved, and craving both grand violence and petty cruelties, but the characters respond by giving into it, by worshipping the “deranged blood God of fog and street violence… who needed worshippers and offered the choices of death as a victim or life eternal witness to the deaths of other chosen victims.”

So, yeah. People think Moore is pessimistic, but he’s got nothing on Ellison. He still believes that a man would, in No Country for Old Men’s terms, agree to “put his soul at hazard.”

Speaking of which, should we talk ownage? Because there’s some quality material in this chapter.

DN: You see sentences like “I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me,” and you have to ask, “How can you NOT find Rorschach at least a little awesome?”

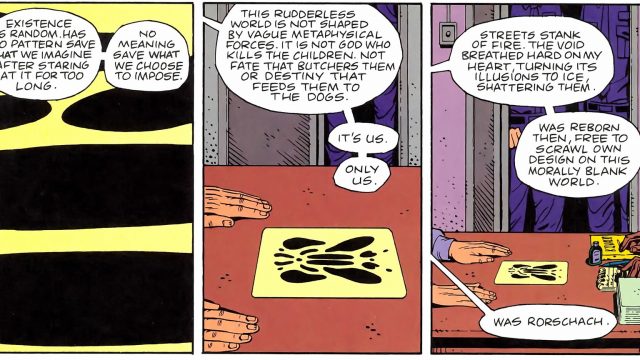

This, of course, means outing myself as a Rorschach admirer, though with strong reservations and a lot of “to be clear”s. It raises an interesting question about what it can mean to identify with a character, especially in the context of a full-on character study like Watchmen – I recall, when I went through Neon Genesis Evangelion last year, saying that I identified with the protagonist of that show more strongly than any other character, and I notice it’s a very similar situation here. Rorschach’s past is completely different from mine, and to be clear I would never go where he does and beat up bad guys in a mask, but I intuitively click onto the decision-making process that gets him from one to the other – not just his existentialist views, so beautifully expressed on page twenty-six, but that overall structure of his flashbacks, of having a lifetime to experiment with and refine his moral outlook based on new information that comes in.

When he says “was free to scrawl own design on this morally blank world”, he meant every word of it, and while his motives and his output might be alien, I can’t argue with his methods. Perhaps to identity with a character means to see your overall morality reflected in a them – to be able to say ‘I understand the decision-making process here, and even if I wouldn’t do this, I would do something like this in this situation’.

ZZ: We will have to call this Rorschach Lovers Not So Anonymous, then, because this reread has installed him as my favorite character of the novel. I don’t know if I identify–that’s always been a peculiarly hard thing for me to decide–but I love him, definitely, and despite the fact that I would do virtually nothing that he does, I respect and even admire him.

He lives with pain, paranoia, and misery, but he distills the mess inside his head and life into concrete, comprehensible actions. The overwhelming postmodern temptation is to sit around and dwell, and Watchmen gets that and isn’t particularly judgmental about it (Laurie and Dan have mostly succumbed to that, and they’re kind, well-intentioned people), but Rorschach acts. He’s the one who scrawls the meaning for everyone else to decide what they think of it. Which is something that’s largely irrelevant to him.

Just as well, because there’s certainly no impartial judge here. Even though I think his innocence is improbable, Dr. Malcolm being a flawed character in his own right rather than just a lens is probably one of the best choices behind the writing of this chapter. He’s not above it all anymore than anyone else.

DN: Ironically, considering his final fate and that Moore realised where he’d end up in the process of writing chapter four, Rorschach is the one character who has figured how to live from one day to another. As you say, Dan and Laurie struggle with inaction and anxiety, and this even leads to their better qualities; Adrian’s search for the one perfect action to fix everything will make him genocidal. It’s Rorschach who recognises that there is no ‘end’ (I’m very carefully talking around a particular quote here), and that the perfect action isn’t one that fixes everything, but one that you get up and do every day (in his case, beat up criminals). What makes me forgive Dr. Malcolm’s implausibility is that his story will end with him recognising that, and finding his own way of acting upon it.

SCATTERED THOUGHTS

- DN: Only now do I realise (and this will enrage two entirely different kinds of people) that the things I admire Rorschach for are the exact same things I admire Peggy Olson for.

- DN: Love that the differences between Walter-wearing-Rorschach’s-face and Rorschach are visible in the way he carries himself pre- and post-Roche. Rorschach throwing oil in a prisoner’s face is stiffer than Walter exploring the dress-maker’s.

- DN: Rorschach loses his button between pages 21 and 24, when he attacks the dogs.

- ZZ: I’m also impressed with the rigidity of Rorschach’s facial expressions when we can finally see them. Compare that to the shifting pattern of his “face,” and there’s a way in which Walter Kovacs really does seem like the less expressive mask.

- ZZ: Love Dr. Malcolm’s dinner party getting ruined because he can’t stand the cutesy “we’re normal, everyone else is weird and that’s hilarious” condescension of the dinner guests. The fact that the moment they’re gone, his wife’s response to all this isn’t even partly concern but is instead anger and “crude sexual insults,” substantiates the feeling throughout this chapter that civilization is thin, false ice.

- ZZ: Adventures in psychology: Rorschach’s patient history first notes that his mother was a known prostitute and then can’t think of a single reason why young Walter might not have wanted to talk about why he beat up the two older boys, unless it was a purely unprovoked attack. There’s an empathy failure going on there.

- DN: There’s not much of interest to me in the sample at the end, other than putting all the dates together and realising Walter put on the Rorschach mask when he was twenty-four, and the Roche case happened when he was thirty-five. As always, slowly getting older than pop culture characters is a strange experience.

- ZZ: One more time for good measure: “I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me.”