We take it for granted that anyone reading this has read Watchmen and seen the film. So, SPOILERS ahead.

DN: When nerds talk about deconstruction, they are almost certainly thinking of the book Watchmen. It took the trappings of the superhero genre asked “why would people put on a costume and beat up criminals, and what would the world actually look like if they did?” and this totally blew people’s minds and changed the superhero genre forever. Or at least, that’s what I’m told; I heard about the comic around 2007, and first read it in 2008 in preparation for Zack Snyder’s film adaptation. I’ll cop to not being much of a superhero guy; I grew up loving Spider-Man and liking Batman, but only when those two are basically locked into their own universes. I cannot believe in a world where an entire society of people decided to put on spandex and beat people up and somehow the world keeps spinning the same way.

Which, of course, is what I like about Watchmen. With the exception of the more fantastic Dr Manhattan, each character has a plausible reason to play out tropes of the superhero genre; I don’t believe that Spider-Man and Iron Man would hang out, but I do believe that Walter Kovacs would wear a mask and beat up criminals (further, it makes complete sense that he and Dan would fight crime together; Dan’s the only one who’d not only stand being around him but enjoy it). And this goes for their effect on the world around them – of course America would use an invincible god to win Vietnam. It’s pleasing to read for the same reason science fiction is pleasing to read – being exactly what we’d expect while nothing like we’d imagine, to steal a phrase from Peter Campbell.

ZoeZ, how would you characterise the appeal of the comic?

ZZ: Like you, I also read this for the first time in 2008. As far as I can tell, it did indeed change the superhero genre forever: most of the guys and girls in capes I grew up with sprung up in the shadow of Watchmen and, even when not modeling themselves after it, couldn’t ignore it. It’s in Batman Begins with Bruce Wayne’s tongue-in-cheek commentary on his alter ego: “Well, a guy who dresses up like a bat clearly has issues.” It’s in, most of all, the increased sense of superheroes existing in the real world and having psychologies at all.

And also like you, I didn’t have a particular interest in superheroes as a kid. I watched the movies—some of the movies—but I didn’t read the comics. So all of the above, to some extent, I have to take on faith. I’m on firmer ground talking about how Watchmen interacts with novels in general. To begin with, the fact that I can assume that no one is going to come into this post to argue that I just can’t do that is part of Watchmen’s legacy of legitimizing comic books as (graphic) novels. But that particular conversation has been had enough times that we can probably leave it at that.

The real impact Watchmen had on me was through Moore’s combination of disillusionment and purpose. This is a world full of disappointment and quiet desperation. Literature deals with mundane dissatisfaction on a routine basis, but there’s a valuable estrangement in seeing that tackled in the colors and styles of superhero comics: because they don’t belong in the aesthetic, or didn’t until Moore, every bald patch or paunch or tense marital conflict makes the fact of human weakness fresh. But what I think makes this novel remarkable, and what its best imitators understand, is that Moore doesn’t only deconstruct. He finds the implausibilities of superheroism—the perfect abs, the blithe lack of PTSD, the eternal youth—but he also finds the possibilities and certainties, of genuine heroism, resistance, and even wonder. There are events and choices here that hit so much harder because we know that they come from people and that they come with consequences.

Almost more than anything else, I think what Watchmen gives us is a fuller sense of the risk of dressing up in a costume and fighting bad guys. Not just the sensationalized risk of kidnapped loved ones, but the psychological risk of growing into someone less and less suited for normal society and the moral risk of making the wrong choices.

DN: That’s an excellent point with the mixture of genre elements and traditional literature elements – someone once pointed out that Gibbons’ art is neither fully realistic nor fully comic book; he chooses mainly to play with secondary colours like purple over the bright primary colours of most superhero comics, meaning we’re more Gothic than real life but more realistic than traditional superhero comics, an inbetween world, and that reflects the story.

Your point about disillusionment specifically makes me think; the traditional complaint about deconstructive works is that they ruin the fun of genre, but maybe that’s looking at it the wrong way around. Maybe filtering these feelings through the fun of genre is what makes them easier to process.

With all that in mind, let’s talk about the first chapter.

The thing that strikes me about it is how elegant it is. The Comedian’s murder is what drives the plot forward, and it’s the very first thing we see, and it leads to Rorschach visiting each of our major players. And inbetween the action, we’re introduced to both the two major themes of the comic – a world with superheroes, and disillusionment – and the significant stylistic element, crosscutting, in the way we’re shown both the Comedian’s murder and the cops investigating it.

What are your initial thoughts on the chapter?

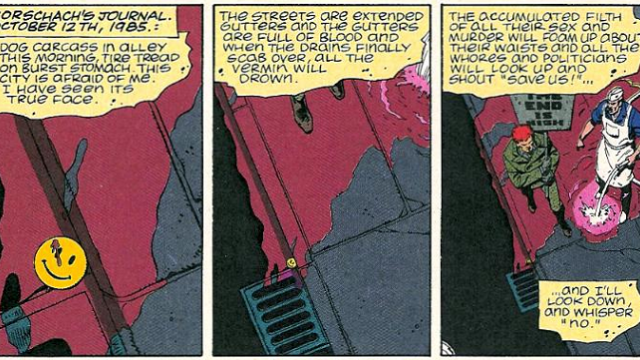

ZZ: Stylistically, in particular, I love how the chapter opens with Rorschach reflecting on blood filling the gutters and then all the flashback panels of the Comedian’s beating and death are drenched in red. Rorschach is the one who cares, so it’s his perspective we’re in when we see that scene. This violent sign of things to come.

The chapter is elegant in its characterization of Rorschach, too. His diary is a morass of anger and disgust, a series of judgments he’s mostly absent from. In a world without superheroes, Rorschach is depressed, violent, and unstable—there is a fair bit of underrated humor in Watchmen, and one of my favorite jokes is Rorschach asking, “That’s what they’re saying about me now? That I’m paranoid?”—and definitely not someone who can work his way to a happier life through self-analysis or healthy self-expression.

Put him in a trenchcoat and give him a mask, though, and he gains something. He becomes pure purpose and pure competence—the panels of his mostly silent investigation of the Comedian’s apartment feel like a very distilled police procedural—and he also becomes someone with better motives than you would deduce from the diary alone. The circuit he makes to introduce us to our main characters is part investigation, but it’s also genuine outreach to the only people he’s loyal to.

What do you think of the introductions that get made here? If Rorschach is all action, what starts off defining the others?

DN: Your observation on the humour reminds me of the other aspect of the crosscutting introduced: ironic commentary from one time on the other. “Ground floor, comin’ up!”

As far as introductory lines go, “A live body and a dead body contain the same number of particles. Structurally, there’s no discernable difference.” is about as iconic and straightforward as you can get. I actually do kinda like that Dan and Laurie, as the ‘normal’ people in this, don’t get iconic lines but do get actions that set them up – Dan’s only real action is reliving the old days, and Laurie’s is complaining about them. I really love the sleight of hand going on with Adrian – he’s the closest to a traditional pulp hero, friendly, humble, and polite, and he genuinely seems to be thinking over what Rorschach says to him – I really like the frame “Sure. Have a nice day.”

Your observations on Rorschach are making me think – it’s a pretty common observation that Rorschach’s journal has very purple prose and his speaking voice is very taciturn, but even more than that, his journal is as you say full of judgements and emotion while his voice is all action – he speaks almost exclusively in facts, or things he perceives as facts. He’ll think that Dan is “a flabby failure who sits whimpering in his basement” but all he’ll say to Dan’s face is “Lot of dust [down here]” and “You quit”. I can’t settle on an interpretation about this – as you say, it’s the difference between Rorschach with the mask and Rorschach without, but perhaps it’s also the difference between what he needs to process and what he doesn’t. I may need to get further into the comic to decide what it means.

Back on the introductions, what I like is how this chapter also introduces us to the relationships these characters have, both between each other and between them and their world. Obviously, there’s Rorschach’s opinions on everyone and their opinions on him – Dan is my favourite, being slightly upset to see Rorschach but immediately suppressing it and offering to heat up his beans, which lays the groundwork for the psychology of their teamwork, but the seeming mutual professional respect between Rorschach and Adrian is a close second* – but there’s also Laurie as a professional Lois Lane (hmm, never noticed that alliteration), and the way Dr Manhattan and Adrian have folded their superheroics into society vs how Rorschach clearly hasn’t. I assume we’d both see Watchmen as literature over drama; the comic begins by showing us the consequences for the heroes’ morality before they show us the full morality itself, let alone the cause.

*One thing that I like about the film is that Snyder chooses to have Dan go to Adrian instead of Rorschach, implying the personal relationship between the two of them instead. It doesn’t work for the story because it makes Dan too proactive, especially at this stage, but as a bit of fanfiction I like it.

ZZ: Dr. Manhattan does get the iconic line, and I like that: it fits with him not being human. And it even suggests he might, to some extent, process the world in icons, in concepts that may never exactly gel with the reality of the people and world around him. It’s also the first time we’ll see him fundamentally unbothered by something that humans are instinctively bothered by, which is something that will be coming back. And Adrian is someone who has consciously, deliberately made himself into an icon–all the better for marketing–and whose civilian-wear purple suit is distinctive in a way that Dan and Laurie’s civilian clothes aren’t. I like this in particular because it works both as part of Adrian’s own cultivated image and because it works subtextually, too. No matter how distant he seems from Rorschach, he’s the one who is really closest to him, still in the same world.

Dan’s broad shoulders might work in the same kind of way, funnily enough. Rorschach calls him flabby, and there are times throughout when the art will show that, but for a lot of his chapter, he has a worried accountant’s face on Bruce Wayne’s body. He’s still thinking over what he wants to do, but he has the capacity to do it.

I want to keep your idea of Laurie as professional Lois Lane in mind as we go forward, because this chapter does a good job of presenting, subtly, what she might already be chafing at in that role. The first thing we see of her, after all, is her dwarfed by Dr. Manhattan. (She’d be stuck in his shadow if he cast one, but he doesn’t: Laurie and Rorschach do, though.)

It’s a small point, but I like that this chapter ends with reminiscing on Captain Carnage, everyone’s former occasional adversary who would pretend to be a supervillain so he could get beaten up. It completely works as remember-when shoptalk, even down to the punchline of the story depending on their knowledge of a coworker. Being a hero may be a vocation, as Hollis Mason points out, but here it also feels like a profession, and that helps sell the reality of it all.

Shall we move on to Under the Hood?

DN: First, I wanna address your observation on Adrian there – I really like that, because Adrian and Rorschach are absolutely inside-out versions of each other. Both looked at the world and saw evil, and decided it must be fought; they each chose completely opposite scales to work on, and have completely opposite reactions from society. I notice they even wear suits with the same shade of purple (most obvious in the middle panel of page 17). Each even wears a mask – Rorschach wears a literal one that separates him from society, Adrian’s is more psychological and seems to make him fit into society while actually separating him from it even further – one of the things that makes the final revelation work so well is that Adrian is always at a distance in the narrative, and it’s clear that he barely notices individual human beings.

But moving onto Under The Hood! Internal documents within a work of fiction are one of my favourite narratives tools, and Watchmen delivers everything I love about it (we’ll get to it when we get to it, but Chapter XI ends with a powerfully emotional use of the idea). Under The Hood works as exposition on the world we’re gonna be playing with, and of course its existence within the world drives some of the story forward (Laurie references it before we even see it, with the Comedian’s attempted rape of her mother). It’s the origin story of our world, and Moore really makes it seem plausible that an adult in 1938 would dress up as a superhero and fight bad guys.

My favourite aspect of the whole thing is how Mason is both openly embarrassed and openly proud of his work – it really captures what you said about how Moore works with both the ridiculous and sublime aspects of the genre. I also love that there’s no single person it starts with – multiple people got it in their heads to do this, and it just happened to spread. And backing up, the story of Moe Vernon that he opens with is both nuts and seems like the sort of thing that must have happened to somebody – it’s a big sign that this world was already a little nuts and sad and beautiful even before superheroes got anywhere near it.

Your thoughts?

ZZ: The Moe Vernon story works as a great encapsulation for the “superhero feeling” we’re seeing from a lot of different angles. Genuine tragedy is encountered with ridiculous trappings; comedy and further tragedy ensues. This is the way the world is–I like your “a little nuts and sad and beautiful” phrasing–and the superheroes are the ones who see and fully engage with every part of that, who will (and who maybe have to) work through the ridiculous to combat the bad and achieve the good.

I dressed up. As an owl. And fought crime.

I’m with you on loving internal documents in fiction, especially ones like this, where the document itself is a character to the extent that the other characters have relationships with it and reactions to it. You can already see, for example, why Rorschach doesn’t like it. What really sticks with me, though, is the warm melancholy of the older Mason’s nostalgia. Young Hollis Mason misses the days of moral clarity, even though he knows, and knew even then, that they weren’t real; old Mason misses “those old New York faces.” There is a real sorrow to that line about certain kinds of faces predominating for a while and then vanishing from photographs. Masked heroes have that same feel to them here. Like you said, it seems to have just been the time for it, and as Watchmen opens, it seems like that time has passed, that the faces are fading.

But, well: we’ll see.

DN: I like the idea that Rorschach also dislikes the book just on the basis of the prose style. That was initially a joke until I realised just how divergent Rorschach and Mason’s writing styles are, and what that says about Moore’s talent.

Casually flipping through the first chapter, so many lines that articulate what you mean pop up.

On Friday night, a comedian died in New York. Someone threw him out of a window and when he hit the sidewalk his head was driven up into his stomach. Nobody cares. Nobody cares but me.

It’s just I keep thinking, “I’m thirty-five. What have I done?”.

Those were great times, Rorschach. Whatever happened to them?

There are so many frames, too, of people sitting and reflecting. There’s a sense of taking stock permeating the chapter, connecting the disparate beats. We’ve caught the world as it takes a breath and looks over what its done, beginning with recognition rather than ending with it. I want to keep that idea in mind as we go on, because I’m wondering if what we’re seeing is a transition world, much as Mad Men presented itself as the transition between the Fifties and the Seventies. Successful literature has an underlying emotion tying everything together; what ties Watchmen together is the fear that you’ve wasted your life on something stupid.

SCATTERED THOUGHTS:

- DN: Love Rorschach playing with the Ozymandius doll on page 17.

- Ownage Count: Rorschach breaks two fingers on a dude, to no avail. Jon teleports Rorschach right in the middle of the vigilante insisting he’s not leaving. “Hurm.”

- ZZ: I love the panel of Dan sitting on the box, slumped, while the empty Nite Owl costume stands rigidly behind him in its closet.

- The sound effect choices for Rorschach eating cold beans are positively Lovecraftian.

- We have our first appearance of an unmasked Rorschach, though here his identity is guessable but not certain. He’s carrying a sign that says THE END IS NIGH, which is both disguise and what superhero instincts look like when they don’t get heroic expression.

- DN: On page 25, there’s a man with a glorious moustache who is quite physically intimate with the fellow sitting next to him, and fans guessed it was a long-retired Hooded Justice with his lover. I think Gibbons denied it, but the intertextual nature of Watchmen definitely allows for that interpretation (I still go with it).