We take it for granted that anyone reading this has read Watchmen and seen the film. So, SPOILERS ahead.

ZZ: This is a remarkably dense chapter, not only in its ideas but in the sheer quantity of the text: a perfect example of style working in the service of theme. “Watchmaker” is about reflection over action, after all.

It’s arguably kin to Arrival and Ted Chiang’s original short story, “Story of Your Life,” where the ability to see your life from a top-down perspective changes the nature of decisions and makes it impossible to active rather than passive: the best Louise and Jon can do is to be deliberate, to know their actions and their consequences as they’re committing to them. One of the brilliant and bittersweet parts of this chapter is that Jon has something of this passivity even before the accident that transforms him into Doctor Manhattan. It’s a small but great touch that Janey takes his genuine remark about other people making all his moves for him as a flirtatious move on its own; that decision, her decision, effectively kickstarts their relationship. But what makes this more tragic for me is that it isn’t just Jon’s character that’s fixed but his fate, and his fate is fixed even before he has the complicating ability to know it’s coming: well before the accident, he still catches a reverse deja vu glimpse of his future. Nothing has been done yet; everything has been done already.

You can see why he would want to create life. It’s one of the things that inherently has the potential to get out of control.

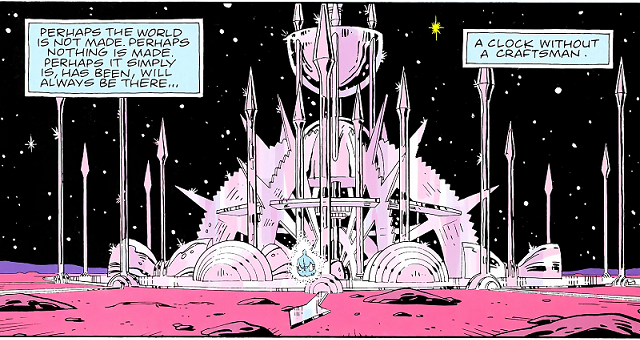

And speaking of creating life, the recurring discussion of Jon’s godlike powers gets particularly layered here. Jon’s reflection on the nature of the world–”perhaps it simply is, has been, will always be there… a clock without a craftsman”–is a nod to the classic Christian apologia of the “watchmaker” (effectively, that the world is an extraordinarily complex system; if you came across a watch lying on the beach, you wouldn’t think anything so orderly could have arisen by accident, you would presume the existence of a watchmaker); he doesn’t take up the traditional rejections of this analogy, either. To Jon, the issue is that the universe is in fact very much like a watch, not a set of occurrences but an object, something that can be seen (at least partly) in its entirety; if there’s no linear time, there’s no concept of a beginning and therefore arguably no concept of a prime mover.

But, of course, all of this is incomplete, and Jon’s understanding, though great, is still partial. Part of that comes up, allusively, here, as Jon tries to give “a name to the force that set [the stars] in motion”; something Dante’s Paradiso refers to as “the Love that moves the sun and other stars.” Jon says it himself: he doesn’t think there’s a God, but if there is, it isn’t him. Here, the story proposes that he might be above–literally–all the action, but he’s not, and he’s going to be drawn into it as a participant soon enough.

DN: In a way, it’s where the style of the comic is allowed to fully flower, like Moore and Gibbons have been holding back for the sake of being legible and now the reader understands the language of the comic enough that they can just talk. I forget who it was that said “Watchmaker” shows us the world from Dr Manhattan’s view of it, but I wonder if it’s actually the view of Moore and Gibbons themselves. Certainly, the techniques used to sell us on Jon’s view are emotionally involving – not just the jumping through time, but the recurring single images, like him dropping the photograph, like his hand holding a tool over the cogs, like his and Janey’s hands over the beer; the joy of these moments coming at the same time as the knowledge that they contributed to Jon’s anxiety now.

I too noticed Jon’s pre-accident passivity, and I found it interesting as part of the deconstructive side of the comic. Accidents causing superheroism are a common part of the genre, and often add a layer of destiny to the proceedings – Peter Parker gets bitten by a radioactive spider and now he has to use them to help people. Moore amplifies the fatalism by giving the accident to an already fairly fatalistic man (pre-accident Jon even looks kinda like Peter Parker, now that I think of it).

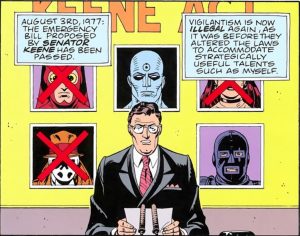

Structurally, the comic is almost entirely flashback (which makes sense for a man like Jon). With one exception, the comic alternates between an issue pushing the plot forward and an issue exploring someone’s backstory; the influence on Lost is obvious. The internal structure of the comic, meanwhile, reverses how the Comedian’s chapter worked; rather than one man through many eyes, we see everyone else through Jon – the meeting with Hollis Mason described in Under The Hood, the passing of the Keene Act, the Crimebusters meeting. It’s a true science fiction story – taking the idea that science fiction is about a technology changing the world – from the perspective of the technology itself; I love that his meeting with Hollis is essentially one man gently explaining he’s made the other obsolete.

ZZ: I’m glad you pointed out the general superhero theme of characters given powers by action and made heroic by choice, because I was thinking about that in relation to Jon’s transformation as well. It’s an agonizing ascension: not only do we see the pain he’s in, we see the terror and helplessness he’s subjected to beforehand as he’s forced to wait for his unavoidable death. (It makes me think there’s a psychological connection between Jon, trapped in a glass cell, panicking and surrounded by people who can’t help him, and Jon, all those years later, teleporting everyone in the studio outside so he won’t be stared at as he goes through another crisis.) The accident gives him superhuman abilities but what it does, first, is kill him.

Janey says, later, that Jon put himself back together–in a nicely gruesome fashion, nerves and veins and muscles slowly stringing themselves back together into a body; you can feel the connection to his earlier point about living and dead bodies being structurally identical, since here we find out that he knows from experience–and that makes Jon’s life after death, at least in this form, a choice. We’ve pointed out before that he’s no longer human, and that’s part of the overall thrust of this chapter, but it’s worth noting as well that to the extent that he can, he chooses to be human. It takes him years to gradually shed those connections (and those clothes). The complexity of that means that Jon has both a trajectory–moving away from humanity–and an inherent dilemma: if he’s not human, what does he do with humans? For right now, the answer is simple: leave them.

I love what you said about “science fiction from the perspective of the technology,” that’s an excellent way of framing that scene. It’s one of the quintessential Watchmen scenes for me: forceful, universal, empathetic, and strange. The moment can’t even remotely exist outside of its context, but the feelings of it have been around forever.

The same could be said of Jon’s romances here. What do you think of Janey and Laurie?

DN: When we first meet Janey, she comes dangerously close to a misogynistic cliche of a bitter ex-wife, narrowly avoiding it because her choices were motivated by Jon apparently infecting her with cancer (I loved her deciding to smoke a pack a day, because, you know, fuck it). This chapter clarifies how she got to that point, and it’s a sad story of gradual obsolescence from a much more human, much more typical perspective. She and Jon’s buddy Wally are more typical pulp archetypes, the spunky love interest and the aw-shucks buddy sidekick, but Janey acts as our human viewpoint in Jon’s transformation – I love that frame of her, shocked, her hair standing up – and the problem with being defined by your relationship to someone is, if they decide to end it… What do you do?

Laurie is less present in this chapter, but we see the beginnings of her fall into bitterness too by way of seeing her apparently happy. I find it interesting that Jon never really articulates why he’s drawn to her; we cut from him looking at her to him kissing her and back, and the effect is such that he seems to be doing it because that’s what he did, what he will do, what he’ll always have done.

It makes me think… I’ve been wondering how Jon could develop as a person, seeing as how he always knows what happens – and he does change slightly, by the end of it. I think the exact limit of his powers is that he can see what happens, but he can’t read minds. That’s where Jon is on the same level as the rest of us; when he talks about, say, the Comedian’s motives, he’s deconstructing his actions just as much as the rest of us, and the only difference is that he’s working on a bigger scale.

ZZ: I like what you say about the effect of seeing Laurie’s happiness here. The art doesn’t emphasize her youth, but it’s not only explicit, it’s implicit in everything we see her doing before the bitterness sets in: that panel of her casually kneeling down on the floor to stroke Veidt’s genetically-altered lynx is a nice, almost childlike moment. Pure delight in beauty. Similarly, when she, Jon, and Veidt all look out the window, there’s the sense that they’re looking through the falling snow while she, with her head turned, is looking at it. We’re seeing her sense of wonder right before it goes away. It makes me curious about Jon’s assertion in this chapter that Laurie doesn’t mind being forced to retire because she “never really enjoyed the life.” Like you said, he can’t read minds.

And it’s that kind of thing, combined with what you said about him of course always knowing what happens, that makes me think about how Jon changes: not by events but by the way he thinks about them. Which is something we’ll be seeing again.

One of the key quotes within Watchmen is about Jon: “the superman exists and he’s American.” It’s a nice, unnerving touch that that’s technically a misquote, and what Glass actually says is the more chilling, “God exists and he’s American.” This gives Moore the chance to have it both ways–the grander nature of the real version and the meta nature of the misquote–and it’s a perfectly-utilized chance, one that’s entirely in keeping with Watchmen as a whole: something bold and unnerving that was consciously edited to be so less so, and hence is always misremembered.

But to focus on the “superman” version, it’s interesting to set Jon and Clark Kent alongside each other for a moment, because here the story elegantly sets them up to effectively be ships passing in the night: an alien moving closer to humanity and a human moving further away from it. Aside from the classic “how does Superman have sex with Lois Lane?” debate, one of the discussions about Superman has always been this: is he Clark Kent pretending to be Superman, or Superman pretending to be Clark Kent? A man who leaps into heroism when necessary but views the costume as a disguise or a man who must sometimes wear a suit and tie? (Here’s my obligatory nod to Kill Bill Vol. 2, which made a decisive claim on this front.)

This chapter seems to present Jon as the latter option. He’s forced, at first, to disguise himself as what he once was, to wear the uniform of humanity and the uniform he’s given by the government, but as his reluctance to make demands dwindles, he loses that uniform piece by piece, until there’s nothing left of it. No more disguise pretending, even transparently unconvincingly, that, hey, he’s just like everybody else: the cancer story means no one is going to buy that anymore anyway.

The problem is, in Watchmen, giving up the mask doesn’t actually resolve your identity one way or the other. Whatever Jon thinks he’s decided here, he hasn’t.

DN: I’ve always struggled to fit Jon into the whole ‘mask’ thing – as he observes, he has nothing in common with the people who dressed up in costume to beat up bad guys. Framing it as him being a symbol disguised as a person as opposed to the people disguised as symbols makes a lot more sense.

But your discussion of the quote from the end-chapter text naturally brings us to that, “Dr Manhattan: Super-Powers And The Superpowers”. I’m immediately struck by the style; much like Hollis, it’s written by a man who had a style guide beaten into him while growing up (as opposed to me, who inelegantly copies that style), but much colder, though no less emotional – I’m particularly struck by the line just after “God exists and he’s American”. We meet Professor Glass in a few frames in this chapter, and he reminds me of Peter Cushing in The Horror Of Dracula; guided by emotion without being ruled by it.

“If that statement starts to chill you after a couple of moments’ consideration, then don’t be alarmed. A feeling of intense and crushing religious terror indicates only that you are still sane.”

In terms of content, Glass contextualises Jon within the global political situation. I have no idea if he accurately captures the mindset of the Soviets, in WWII or 1985, but it sounds believable – it reminds me of Sun Tzu’s observation that you don’t corner your enemy with no way out, because then he has nothing to lose and no reason not to inflict as much damage as he can before you take him out. His take on the American government, sadly, definitely sounds accurate even up until recently, and it even ties in with superheroics – I get a cheeky thrill out of the idea that superhero stories are another expression of the same particularly American attitude that lead to your country’s various military misadventures. Embedded within this is another acknowledgement that Jon’s powers are vast but not absolute – he can take down only sixty percent of oncoming missiles, and the rest will still wipe out all life.

But I’m also struck by what he never brings up: other superheroes. Will it be any wonder when we get to Dan’s hopelessness? What exactly will a geek in an owl costume be able to do against Russian bitterness and American Omnipotence-By-Association, let alone Jon himself? For the most part, Watchmen looks at superheroes from the ground-level (which still means something even when applied to Jon); these extracts provide precisely the opposite view, showing us how small our heroes really are.

ZZ: Because I just noticed it when double-checking phrasing, I have to note that I appreciate the commitment to the bit that leads to Gibbons/Moore having that floating “DR MANHATTAN:” at the bottom of the final page of this chapter. In context, it’s the left-page side of the full title of the excerpt of the book we’re ostensibly reading. Outside that context, and in the context of Watchmen as a whole, it’s an unresolved situation. Dr. Manhattan: –and from him, whatever comes next.

That goes along with Professor Glass (and now I think we are owed a time travel-aided remake of the film even if just for the chance to cast Cushing in that role) and what you said about the smallness of the “masked avengers” alongside all this. Glass mentions not just a god among men but “gods” plural, but the only real forces that would seem to counterbalance Jon are the forces of countries–and powerful countries at that. It’s Hollis’s electric cars scene all over again: that sudden awareness of how tiny you are and how much of what you’re trying to do can be overturned in a moment by someone else.

…When I put it like that, I can see how this novel gets its reputation for grimness. But again, of course, the story doesn’t end at chapter four, and definitely doesn’t end with choices seeming meaningless. And Glass, too, remembers that nations are still made up of people, and that people aren’t all the same. His point that the assumption that obviously the Soviet Union won’t pursue Mutually Assured Destruction is “based upon the belief that American psychology and its Soviet counterpart are interchangeable.” History says they’re not; history means they’re not. It’s appropriate for a chapter so intensely focused on what’s already past have that reminder come at its conclusion. What we’ve just read is the story of how Jon became who he is, and then from that, we–and everyone else–will have to guess how he’ll react.

Which at this point, I think, leaves Veidt and Rorschach as the two characters with mostly unmapped histories, and makes them the real wild cards in the game.

STRAY OBSERVATIONS

- DN: The line that haunts me most is “I am starting to accept that I shall never feel cold or warm again.”

- ZZ: Somewhere within the write-up over how Jon’s presence does and does not deter the Soviet Union is the makings of a pretty good crossover episode with The Americans.

- DN: Credit where it’s due: Snyder’s presentation of this chapter is the best part of the film.

- ZZ: I’m wondering if part of the attraction the much-younger Laurie has for Jon is that her reactions to the world are fresh, whereas he mostly has to exist in a state past surprise. At least with her, he gets a certain contact high.

- DN: If you take Jon’s sandcastle as a work of art, it reflects him perfectly: beautiful, majestic, clockwork, and totally sterile. Gibbons achievements as a visual artist cannot be overstated.

- DN: There’s only one traditional moment of ownage in this, an off-hand frame of Jon blowing up a dude’s head. I would also count him sending an entire mob back to their homes.