Social message films or ‘issue dramas’ almost always have the cards stacked against them. Film is a vehicle to spread the word about XYZ, and as such, certain elements like compelling characterization, insight, or decent plotting may fall by the wayside in favor of self-congratulatory smugness and immediate emotional satisfaction. Similarly, social message films often are so of their time, they are forgotten within a few years, only to be reexamined as historical oddities down the road. This isn’t meant to be cynical; it’s just the way the system works.

Victim is a haunting and peculiar film, and its greatest success is not only how it’s a legitimately great film as well as a social message piece, but how well it’s stood the test of time. While it’s overarching ‘tolerance for the queers’ message is very much of its early 60s milieu, the film’s portrait of blackmail, a lavender marriage, and the pain and rage stemming from being closeted, remains timeless. It’s fascinating character study under the guise of a taut crime drama. There are so many subtexts to explore, both artistic and political, that it is only fair to review the film as both a work of art and as a social artifact.

Victim as a Sociology Artifact

To understand the full impact of Victim, a brief history lesson is required. In 1961, when the film was first released in the UK, homosexuality was still illegal in the United Kingdom. Homosexuality was not decriminalized in England and Wales until the passing of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. In Scotland, it was decriminalized with the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980, and in Northern Ireland with Homosexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 1982.

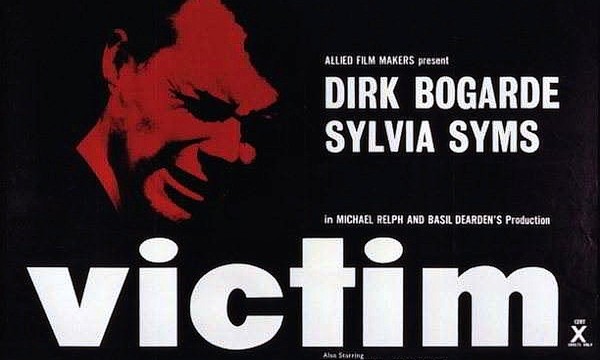

For anyone who has read the Vito Russo book, The Celluloid Closet, or seen the documentary of the same name, Victim is best remembered as the first film in the English language to use the word ‘homosexual’ (the 1919 German film, Different from the Others, was the first film to use it in any language). Beyond that landmark, the film’s production history is its own treasure trove of trivia. Following the critical and commercial success of the race drama, Sapphire, which won the BAFTA Film Award for Best British Film, screenwriter Janet Green found her inspiration for Victim via the Wolfenden Report. The Wolfenden Report, headed by John Wolfenden, analyzed different criminal cases involving homosexuality, in addition to cases involving prostitution. The report, which was published in 1957, suggested homosexual acts between consenting adults be decriminalized and the age of consent be 21. Needless to say, it was a controversial stance in 50s-era Britain. However, Green became a supporter in the decriminalization of homosexuality, and along with screenwriter John McCormick (both of whom would receive a BAFTA nomination for their work) and director Basil Dearden, who Green had previously collaborated with on Sapphire, Victim was born. Given the film’s controversial subject matter, many actors and actresses allegedly turned down roles in the production. However, Dirk Bogarde and Sylvia Syms were cast as the leads. Neither actor publicly expressed any discomfort with the material; if anything, they were delighted by the opportunity. Bogarde was at the height of his popularity, having started in the popular Doctor series, along with playing the leads in productions like A Tale of Two Cities. Victim was his chance to establish himself as one of Britain’s greatest actors, which he did with aplomb.

Despite the pedigree of the project, Victim was not without its battles with the censors. Due to its sympathetic portrait of homosexuality, the BBFC had more than a few objections. Some scenes were cut, including a few, according to IMDb, involving teenagers. To the best of my knowledge, these scenes remain lost. But, the BBFC’s reaction was tame in comparison to Hollywood Production Code, which outright refused to approve the film for release in the States. However, the Hollywood Production Code’s power was waning in the early 60s, no doubt exacerbated by films like Psycho and Suddenly, Last Summer. Given that Victim was made outside of the US, it is widely presumed that is how it was ultimately granted approval sans cuts in 1962.

But, that’s just the history, so what about the success? Victim, along with other 60s films like A Taste of Honey, The Leather Boys, and Darling are credited with helping change the public opinion on homosexuality to a more positive one, and, in addition to the Wolfenden Report, leading to the eventual decriminalization of homosexuality via the Sexual Offences Act 1967. Call me old-fashioned, but that strikes me as a pretty big success.

Earlier in my piece, I mentioned that social message films are frequently ravaged by age, and what was initially groundbreaking and bold can later be seen as mawkish, condescending, or downright offensive in its own right. It’s a tricky balancing act. To use a literary comparison: reading something like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and expecting the nuance of a contemporary novel like White Teeth is a set-up for disappointment. Reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin and analyzing what made it groundbreaking for its time while also examining, by contemporary standards, it’s limitations and failures, is a bit more fair.

I watched Victim fully expecting it to be an earnest, possibly mawkish exercise in ‘the queers are just like us!’ mentality. I was stunned by how nuanced, thoughtful, and complex the film was with its depictions of the lead character, Melville Farr, a closeted barrister, and his relationship with his wife, Laura. Which leads me to….

Victim as a Work of Art

So, you’ve read about the history and social importance of Victim, but what about the film itself (oh, yes, that)? Well, it’s essentially two films for the price of one. On the surface, it’s a crime drama about blackmail and paranoia; a vehicle for the film’s message that gay men are prosecuted by both amoral schemers and the government. Beneath its genre trappings, it’s a raw character study of a closeted man whose own intimate secrets send ripples through his marriage.

The film opens with young gay man, Bartlett (Peter McEnery), who is being blackmailed. Following his arrest for theft, he commits suicide. Melville Farr (Bogarde), a rising barrister, hears of his death and given his prior acquaintanceship with Bartlett, sets out to find the culprit. He begins to find gay men all over London are being blackmailed. He plots to set a trap to ensnare the blackmailers soon lead to threats against his own marriage and career.

Of the two storylines, the blackmail plot feels a bit slight. The film beautifully conveys the horrors of blackmail. Despite Philip Green’s occasionally bombastic score, Dearden’s accomplished direction gives the film a finely wrought sense of dread. Green and McCormick’s screenplay is smooth, if a a bit lacking in material for the supporting characters. This feels more like a necessary evil; the film aims to educate the audience, who presumably at the time were not terribly sympathetic towards queer men. The supporting characters fall into dichotomous categories of good and bad: there are the long-suffering queer men and those who are sympathetic to them, and on the other side, you have the quietly prejudiced (the screenplay argues they are merely ignorant) and the outright villainous blackmailers. The most multifaceted, complex characters are Farr and his wife, Laura.

Needless to say, by virtue of being the most complex characters, the scenes between Bogarde and Syms are the most electrifying to watch. The two actors have an easy chemistry, giving their relationship gravity; when Laura confronts her husband, the tension is almost unbearable. The screenplay cleverly leaves hints that she may have known about her husband’s predilections from past events (a ‘friendship’ in university, which may have been a bit more), so her confrontation is less rooted in the anger of her husband’s sexuality, and more in his general infidelity. When Farr shouts at her, ‘I wanted him,’ it still packs a punch more than 50 years later. The whole scene, along with their marriage subplot in general, could have dissolved in histrionic nonsense. Instead, Bogarde and Syms give it a poetic sadness with faint slivers of hope. Their marriage is first and foremost a great friendship. In one of the film’s most powerful, heartbreaking scenes, Laura tells Farr that she will not blindly accept his apologies because it wouldn’t be fair to her. The scenes between Bogarde and Syms compliment the blackmail plot, giving additional emotional weight to Farr’s decision to pursue the blackmailers, even at potential destruction of his marriage and career.

****

The most remarkable aspect of Victim, besides its nuanced portrait of a lavender marriage and its sympathetic portrait of queer sexuality, is Dirk Bogarde’s BAFTA-nominated, incendiary performance. His Melville Farr is one the great characters of cinema, regardless of orientation. Bogarde avoids turning Farr into a self-righteous martyr or a damaged weakling. Farr is collected and intelligent, but resentment and bitterness burn beneath his cool demeanor. When one of the blackmailed gay men suggest paying off the blackmailers, Farr lashes out at him in such a raw moment of fury, it’s terrifying and heartbreaking. Bogarde wisely avoids making Farr as saint, and the film is all the most compelling because of it. The film showed Bogarde’s formidable talent as an actor, and gave way to other incredible performances in classics such as The Servant and Darling, for which he would win BAFTA Awards for Best British Actor.

In real life, Bogarde was widely known to have been a closeted queer man, although he had never once, not even in his memoirs, publicly acknowledged his sexuality. It is an overused word in describing an actor’s performance, but Bogarde’s work in Victim was brave. Homosexuality was still illegal in the UK, and the role could have destroyed his career. In many ways, Victim can be seen as Bogarde’s unofficial coming out; having starred in the film, he said everything he wished to say about the topic, and that, like they say, was that.